Trending Now

If you’ve spent any amount of time on Facebook in the past year (or week, or day, or hour), you’ve clearly noticed the astronomical number of people who straight-up have no idea what’s actually going on in the world of politics, American or otherwise. It’s not just a matter of voicing different opinions; some people confidently boast their ‘knowledge’ by engaging in the nastiest fact battles over the semantics of pieces of information that aren’t even actual facts.

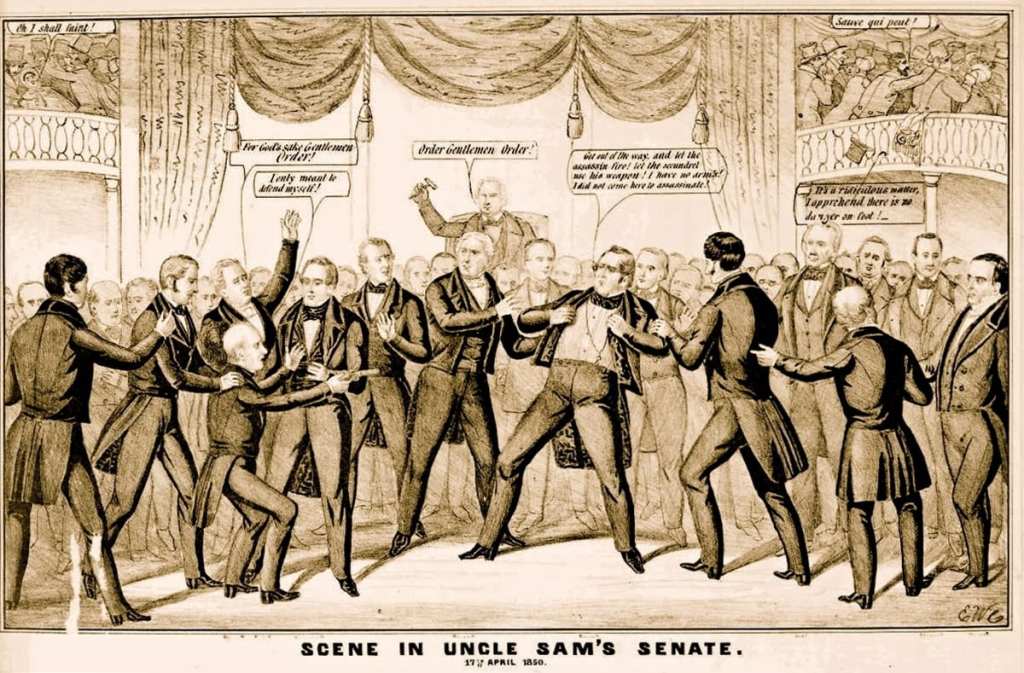

Photo Credit: Someecards

You know what’s super weird, though? 19th-century etiquette experts, that’s what. They actually thought it was possible to politely engage in civilized political discourse. BAHAHAHA. Can you imagine what they would say if they were here today?

I can. They would say: “It’s still possible, a-holes.” Then they would bust out the books and manuals they penned themselves and attempt to set us straight with some sound advice, such as the following:

1. READ STUFF SO YOU KNOW WHAT YOU’RE ACTUALLY SAYING.

“It is very needful for one who desires to talk well, not only to be well acquainted with the current news, and modern and ancient literature of his language, but also with the historical events of the past and present of all countries. He must not have a confused idea of dates and history, but be able to give a clear account, not only of the chief events of the recent Rebellion, but also of those of the Revolutions of the past century, and of the period of the Roman Empire, its rise and fall, and of the various important events which have occurred in England, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, and Russia.”

— From Daisy Eyebright’s A Manual of Etiquette With Hints on Politeness and Good Breeding, 1873

2. BE FREAKING POLITE.

“Retain, if you will, a fixed political opinion, yet do not parade it upon all occasions, and, above all, do not endeavor to force others to agree with you. Listen calmly to their ideas upon the same subjects, and if you cannot agree, differ politely, and while your opponent may set you down as a bad politician, let him be obliged to admit that you are a gentleman.”

— From Cecil B. Hartley’s A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette, 1875

3. REALIZE THAT YOUR VIEWS ARE MERE OPINIONS AND THAT YOU MIGHT BE WRONG.

“Never, when advancing an opinion, assert positively that a thing ‘is so,’ but give your opinion as an opinion. Say, ‘I think this is so,’ or, ‘these are my views,’ but remember that your companion may be better informed upon the subject under discussion, or, where it is a mere matter of taste or feeling, do not expect that all the world will feel exactly as you do.”

— From Florence Hartley’s The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, 1860

4. DON’T RUIN PARTIES.

“A man is sure to show his good or bad breeding the instant he opens his mouth to talk in company … The ground is common to all, and no one has a right to monopolize any part of it for his own particular opinions, in politics or religion. No one is there to make proselytes, but every one has been invited, to be agreeable and to please.”

— From Arthur Martine’s Martine’s Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness, 1866

5. ACCEPT THE FACT THAT YOU WEREN’T BORN TO CHANGE THE OPINIONS OF OTHERS.

“Whenever the lady or gentleman with whom you are discussing a point, whether of love, war, science or politics, begins to sophisticate, drop the subject instantly. Your adversary either wants the ability to maintain his opinion … or he wants the still more useful ability to yield the point with unaffected grace and good humor; or what is also possible, his vanity is in some way engaged in defending views on which he may probably have acted, so that to demolish his opinions is perhaps to reprove his conduct, and no well-bred man goes into society for the purpose of sermonizing.”

— From Arthur Martine’s Martine’s Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness, 1866

6. JUST AGREE TO DISAGREE ALREADY.

“Even if convinced that your opponent is utterly wrong, yield gracefully, decline further discussion, or dexterously turn the conversation, but do not obstinately defend your own opinion until you become angry … Many there are who, giving their opinion, not as an opinion but as a law, will defend their position by such phrases, as: ‘Well, if I were president or governor, I would,’ — and while by the warmth of their argument they prove that they are utterly unable to govern their own temper, they will endeavor to persuade you that they are perfectly competent to take charge of the government of the nation.”

— From Cecil B. Hartley’s A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette, 1875

These are pretty hard concepts to grasp, I know- but I’m confident everyone could figure them out if they actually wanted to… It’s that last part that causes all the trouble, though. Oh well, at least if you’ve made it this far and are still reading, you know you’re one of the world’s few special creatures who want to be sure they know as much as they can about what’s going on. And for that, we thank you. And by ‘we’ I mean me and the other 20 people who read this far. And by ‘other 20 people’ I mean the majestic unicorns of the Internet.

Photo Credit: < a href=”http://www.seedsumo.com/sumo-blog-1/8-common-characteristics-of-every-unicorn-startup”> seedsumo

h/t Mentalfloss