Considering how long ago he lived, we know quite a bit about the life of Alexander the Great. He was born in 356 BCE in Macedonia, was tutored by Aristotle as a boy, and inherited the throne from his father at the tender age of 20. He’s remembered as one of the greatest generals in human history, after conquering parts of Persia, Asia, Egypt and India.

He was a king, a general, a pharaoh and practically a god by the age of 25, but his death was extraordinary in a totally different way.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

The reason for the great man’s demise has been a mystery for all of the intervening 2,000 years. He developed a fever and abdominal pain that soon led to the inability to walk, move, or speak (despite being of sound mind until the moment of his death). But his body didn’t show any signs of decomposition for six days postmortem, and, until recently, no one really knew why.

Theories like poison, liver failure, malaria, and typhoid had all been floated, but Dr. Katherine Hall of the Dunedin School of Medicine recently posited a new theory that makes a great deal of sense. She believes Alexander the Great may have suffered from an autoimmune disease called Guillain-Barre Syndrome, or GBS.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

An acute motor axonal neuropathy variant of GBS can be contracted from a bacterial infection that was common at the time. Hall argues that the reason he didn’t decompose wasn’t because he was a god, but rather because he was alive and cognizant, however unable to move or speak.

“I have worked for five years in critical care medicine and have seen probably about 10 cases of GBS. The combination of ascending paralysis with normal mental ability is very rare and I have only seen it with GBS,” Hall told Fox News.

Yikes.

In 323 BCE Babylon, doctors would have diagnosed death on a lack of breath, cold skin, and pupils that didn’t react to light. But if Alexander was in the end stages of dying from GBS, his breathing would have been shallow, and the other marks of life wouldn’t have been obvious either.

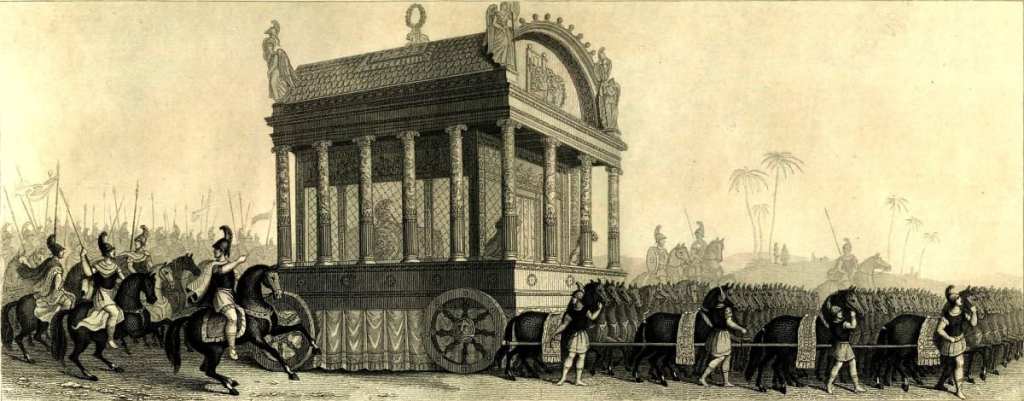

Photo Credit: Public Domain

“His sight would have been blurred and if his blood pressure was too low he would have been in a coma. But there is a chance he was aware of his surroundings and could at least hear. So he would have heard his generals arguing over succession, heard the arrival of the Egyptian embalmers, and heard that they were about to start their work.”

Guys. I’m pretty sure that being embalmed while still alive – at least at the beginning of the process – is one of the most gruesome, horrible ways to die.

There is, of course, no way to prove her diagnosis, but it does rather succinctly explain all of the mysterious factors surrounding his death.

Which, if she’s right, definitely wasn’t fit for a king – or even your worst enemy.