In the modern world, the ideas that gender can only be male and female and that those identities are unalterably set at birth is only starting to change (and only among some sets). But a study of 3,000-year-old Persian graves suggests that the ancient Persian people had a much broader definition.

Though some modern people insist that specific sexual characteristics are attached to strict binary genders, Professor Megan Cifarelli argues that’s just not the case.

“The gender binary is culturally specific, in conflict with many, perhaps most, past civilizations.”

She’s conducted a special study of grave-sites from Hasanlu, a treasure trove of 2800-year-old, mostly undisturbed graves in northwestern Iran. The graves contained items that were likely gendered – some considered male and others female – and buried accordingly. But Cifarelli reports that a good 20% of the graves contained a mix of items associated with both genders.

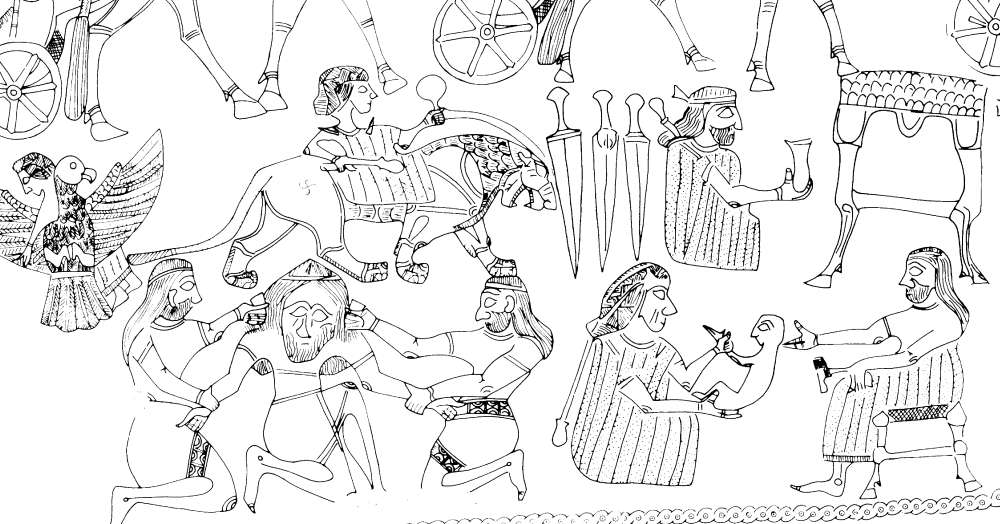

Image Credit: The Penn Museum

She believes that could mean the people who created those graves believed in a third gender, or saw gender as a spectrum as opposed to a binary.

Her theory rests on a golden bowl that depicts a man with a beard performing typically female roles, though she has yet to publish her findings. She’s presented them at academic conferences, though, and Cifarelli says responses have been positive.

It makes sense, since it’s widely accepted that many Native American cultures recognized more than two genders, exemplified by the “two-spirit people.”

If the idea of gender is malleable, it could change more than the way we understand sexual culture and gender roles in ancient societies, but also change the way archeologists categorize the sex of bodies they uncover. Right now, graves are categorized, on occasion, based solely on what sort of items are found with the deceased.

Image Credit: The Penn Museum

“This has been replaced with a medical model, looking at bodies as being sexable via scientific methods,” Cifarelli told IFLScience. “However, for a large percentage of the population we can’t tell.”

She believes some of these people would be classified, in modern terminology, as intersex, and knows that not everyone will agree with – or even understand – her findings.

“People think I must be a crusading radical, pushing contemporary identity politics into the past, but I’m actually trying to lift the weight of the 19th-century identity politics.”

Given the current political climate, the amount of willful ignorance, and a lack of education surrounding the subject, it’s not surprising that presenting her work in public could be fraught with issues. Thankfully there are people like Cifarelli willing to speak for those who can’t – whether they lived 3000 years ago, or are living their best life today.