Trending Now

No matter what you purchase, a pair of pants, groceries, or even a car, you know that you’re always looking for the best deal. And even when you think you’ve scored an item at a good value, many times you’ve been tricked by often-used sales tactics that help sellers secure the deal they wanted you to take in the first place.

Sound confusing? It might at first, but it really makes a lot of sense once you examine how sellers frame their items that are for sale.

For sellers, it’s all about how the options are presented to you. And for consumers, a lot of our decisions come down to psychology and the way our brains are wired.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

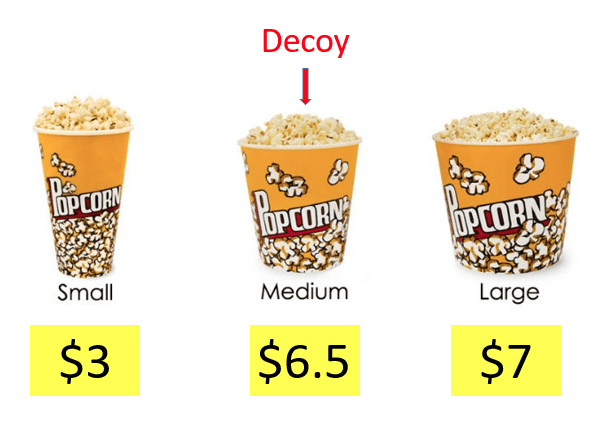

One popular, tried and true method that companies use to sell items is known as the decoy effect, and it has been employed in marketing for many years. When only faced with two options for purchasing an item, people usually go with the less expensive choice. This is when the decoy effect comes into play: companies offer three items when selling a product, a higher priced one (the one they actually want you to buy), a lower priced item (the one they don’t really want you to buy), and a decoy item meant to distract the consumer.

The third option, the decoy, is categorized as asymmetrically dominated. In plain language, the decoy option pushes the consumer to buy the most expensive item because the middle (decoy) option is only slightly less expensive and makes the most expensive item look much more attractive.

Let’s look at an everyday example: buying popcorn at the movies. If a customer is presented with only two choices, they’re probably going to choose the cheaper option because of the price gap.

Photo Credit: HumanHow

However, when a third option, the decoy, is introduced to the equation, the rules change dramatically.

Take a look at how your brain reacts when there are three choices of popcorn.

Photo Credit: HumanHow

Most people would now choose the large bucket of popcorn because it seems like such a better value, getting that much extra popcorn for only 50 cents more.

The decoy effect is employed by businesses big and small all the time, and it works.

Another tactic employed by, well, anyone selling anything, really, is the framing effect. The framing effect causes people to react in different ways depending on how a situation is presented to them.

One example is being presented with a situation that could be viewed as a win or a loss: and this applies to sales as well. Simply put, we’re talking about how things are presented to consumers. And the way things are presented causes our brains to naturally and unconsciously categorize them as positive or negative.

Businesses have the option of framing their products in whatever light they think will make them the most money.

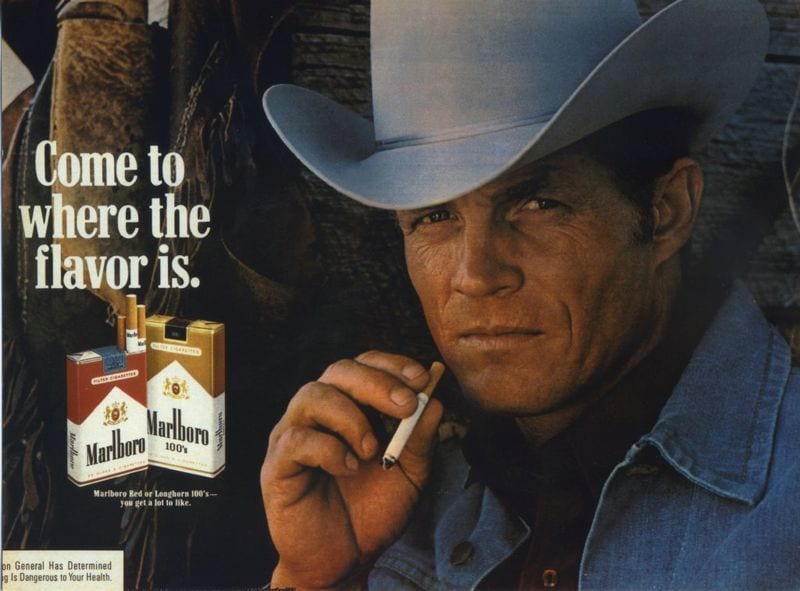

One notable example from the past is the Marlboro Man. Introduced in 1954, the Marlboro Man advertisements framed smoking (Marlboros, hopefully) as a rugged, manly, sexy activity that undoubtedly appealed to men from all backgrounds. Cigarette ads geared towards women played the same framing game.

Photo Credit: Altria

In the 1960s, Virginia Slims ads portrayed women who used their product as worldly and intelligent.

Yes, these products will kill you, but you’ll look really good in the meantime. These are two examples of positive framing in advertising and sales.

An everyday example of framing is right in front of you in the frozen food aisle at the grocery store. People are more likely to buy meat that is labeled “80% lean” than “20% fat”. It’s all in the way the information is presented to consumers.

Yet another strategy used in sales is base rate neglect, a psychological tool that affects consumers in a specific way. Base rate neglect occurs when people are presented with general, generic information AND specific information about a certain topic in order to influence them. When given general and specific information simultaneously, our minds tend to ignore the general and only focus on the specific.

In other words, advertisers use this ploy because they know human brains will likely fail to take into account all background information when presented with a shiny object waved in front of their faces.

Playing the lottery is a perfect example. When a store sells a winning lottery ticket, they make sure everyone in the area knows about it because people will flock there and hope that some of that luck will rub off on them. But what are the odds of actually winning? It’s literally in the millions. But people, and consumers, tend to only see the little picture instead of the big picture backed up with data and facts.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Here’s the weirdest thing about all of this… the evidence shows that consumers actually like being played.

Don’t believe me? Well, you haven’t heard the story of J.C. Penney.

In 2012, J.C. Penney CEO Ron Johnson attempted to be straight with consumers and all the chain’s stores stopped having sales and accepting coupons. Instead, J.C. Penny stores offered products at lower “everyday” prices to attempt to stop manipulating customers with what Johnson called “fake prices.”

So instead of seeing two or even three different prices slashed down, a firm price rule was implemented.

Sounds great, right?

Wrong. Months later, Johnson’s J.C. Penny experiment was over and he was out of a job.

It turns out customers actually love the price manipulation because of the deals (or lack thereof) that they believe they are getting. Shoppers believed they were no longer getting a bargain, and they let their displeasure be heard loud and clear. The visual representation of seeing original prices slashed lower made customers feel less rational about their purchases.

Also, the human brain’s thrill of finding and buying a discounted item and getting a kick of dopamine was no longer there, so the “high” for bargain hunters disappeared.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

So J.C. Penney reintroduced coupons, discount racks, and sales galore, and things went back to the good old days. As we’ve learned, these coupons and “deals” don’t translate into actually saving any money, and we are always paying inflated prices on the goods we purchase.

Now that you are armed with this knowledge, pay attention to how things are sold to you: food, online subscriptions, even cars.

You’ll still probably buy the option the sellers want you to, but at least you’re aware of how the illusion works.

And it’ll come in handy when you start your own business!