Trending Now

Thanksgiving has got to be one of the biggest holidays of the year, a time for parades, travel, family, and of course, tons and tons of food. But, as is the case with many major holidays, it seems that the true history of the holiday has been lost over the years.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Today’s Thanksgiving celebrations are a pretty far cry from some of the earliest recorded mentions of celebrations that went on to inspire the holiday we know and love today. In fact, there’s a decent chance that turkey – undoubtedly the most recognizable symbol of Thanksgiving – wasn’t even served at the original gathering of English settlers and Native Americans! So, let’s take a deep dive through history and discover the truth behind 4 of the biggest misconceptions about Thanksgiving.

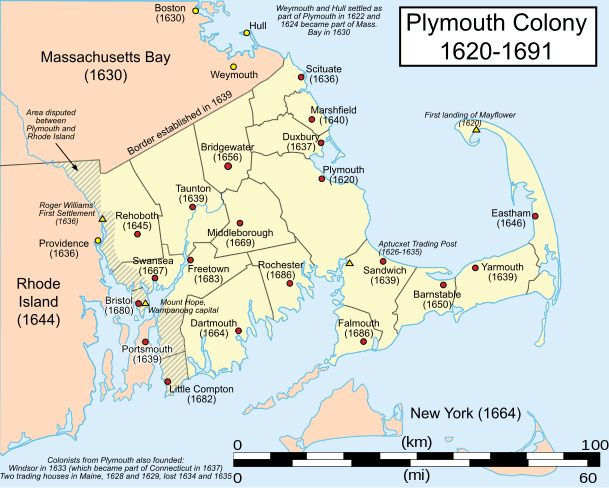

1. There were several “first” Thanksgivings

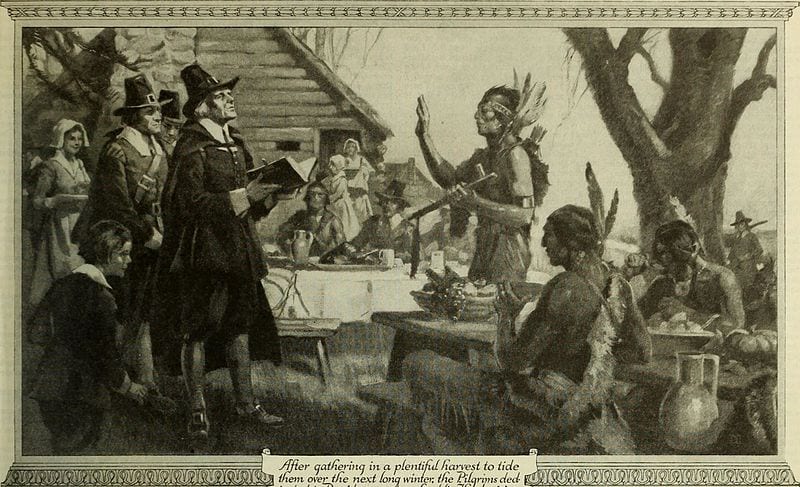

The most prevalent narrative regarding the first Thanksgiving involves English settlers and their Native, Wampanoag counterparts coming together to celebrate the harvest season with a three-day-long feast, which included prayer, various games and displays of physical strength and skill, and possibly some military exercises. This gathering took place in Plymouth, sometime in late November of 1621.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Most grade school history classes claim that this was the first Thanksgiving, but an examination of historical records tells a different story. For one thing, it was several years after the first feast in 1621 that any similar celebration occurred again – which means that the feast was more of a one-off event than the start of a beloved tradition. Thanksgiving didn’t actually go on to become an official, national holiday until Abraham Lincoln declared it as such in 1863.

Additionally, early colonial records indicate that 1621 Plymouth wasn’t exactly unique – neither in celebrating the harvest nor in extending an invite to Native Americans. Harvest celebrations were fairly common amongst both the English and the Natives, and extending an invitation to each other (or important community leaders, at minimum) was just good diplomacy.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

2. The menu was pretty different

Today’s Thanksgiving dinner would be unimaginable without a few staples: mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes/yams, and of course, a roast turkey as the centerpiece of it all. It turns out, however, that there’s a good chance none of those things were eaten at that first celebration in 1621.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

First of all, you can forget all about the potatoes – mashed or sweet. Although European explorers had encountered potatoes (both white and sweet) in South America back in 1570, they weren’t adopted into popular cuisine until long after the 1621 celebration.

Pumpkin pie also wasn’t on the menu. Sure, early settlers and Native Americans had ready access to pumpkins and other squashes, and almost certain ate them during their feast. However, at that time they didn’t have access to butter or wheat flour required to make pies. They also ran out of sugar by the time of the feast, meaning they had no way to create cranberry sauce as we know it today.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Finally, we know that the 1621 feast featured plenty of meat, including deer, fish, and various fowl – but it doesn’t mention turkey specifically. Now, wild turkeys were abundant in the area at the time, so it’s quite possible they were at the table. That said, the “fowl” described in the records may also have referred to geese, ducks, and swans, all of which were also popular choices at the time.

3. It wasn’t called “Thanksgiving”

The harvest celebrations of early colonial settlers may have had some elements that we associate with Thanksgiving today, but they weren’t referred to as “Thanksgiving” until a long time after the fact.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Now, that’s not to say that early colonial settlers didn’t have a holiday called thanks-giving… it just had nothing to do with the seasonal harvest celebration we know today. Thanksgiving wasn’t a once-a-year feast, it was a religious day of prayer whenever people felt a need to thank God for a stroke of good fortune, like rainfall after a long drought or victory in battle. As a matter of fact, one of the earliest recorded instances of a colonial celebration specifically referred to as a “thanks-giving” was to honor colonial soldiers returning from the massacre of an entire settlement of Pequot men, women, and children in what is now Mystic, Connecticut.

4. It wasn’t the start of a beautiful friendship

While the celebration in 1621 Plymouth was certainly an important, positive moment in Pilgrim-Native relations, it’s more accurate to characterize it as a rare bright moment in an otherwise very rocky relationship.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

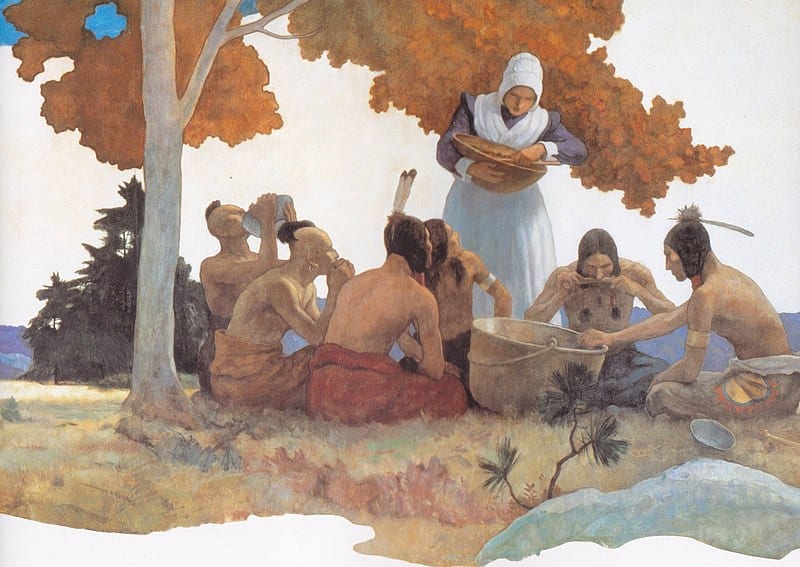

Native Americans did help teach early settlers how to cultivate indigenous crops, which was vital to the survival of early colonies whose own seeds from England had largely failed. The Wampanoag and their leader Massasoit (who were present at the 1621 celebration) were crucial allies to these early colonists… but relations grew strained over time.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

As more colonists began pouring into the region by the thousands, they increasingly ate up more and more land that had previously belonged to the Natives. They also brought over foreign diseases that wiped out large tracts of the Native population. A generation after Massasoit feasted with the English settlers, his son Metacomet was engaged in a brutal conflict with them – one that ended with his head mounted on a spike outside of Plymouth, and his wife and son sold into slavery.

So yeah – a little different from what you learned in third grade social studies.