There is so, so much about American history that they don’t teach us in school, and to be honest, the more I learn, the more I think they’ve definitely left out the best parts.

Or at least, the most interesting ones.

One of the areas where education is sorely lacking is pretty much anything revolving around Native American history that doesn’t specifically intertwine with the European narrative.

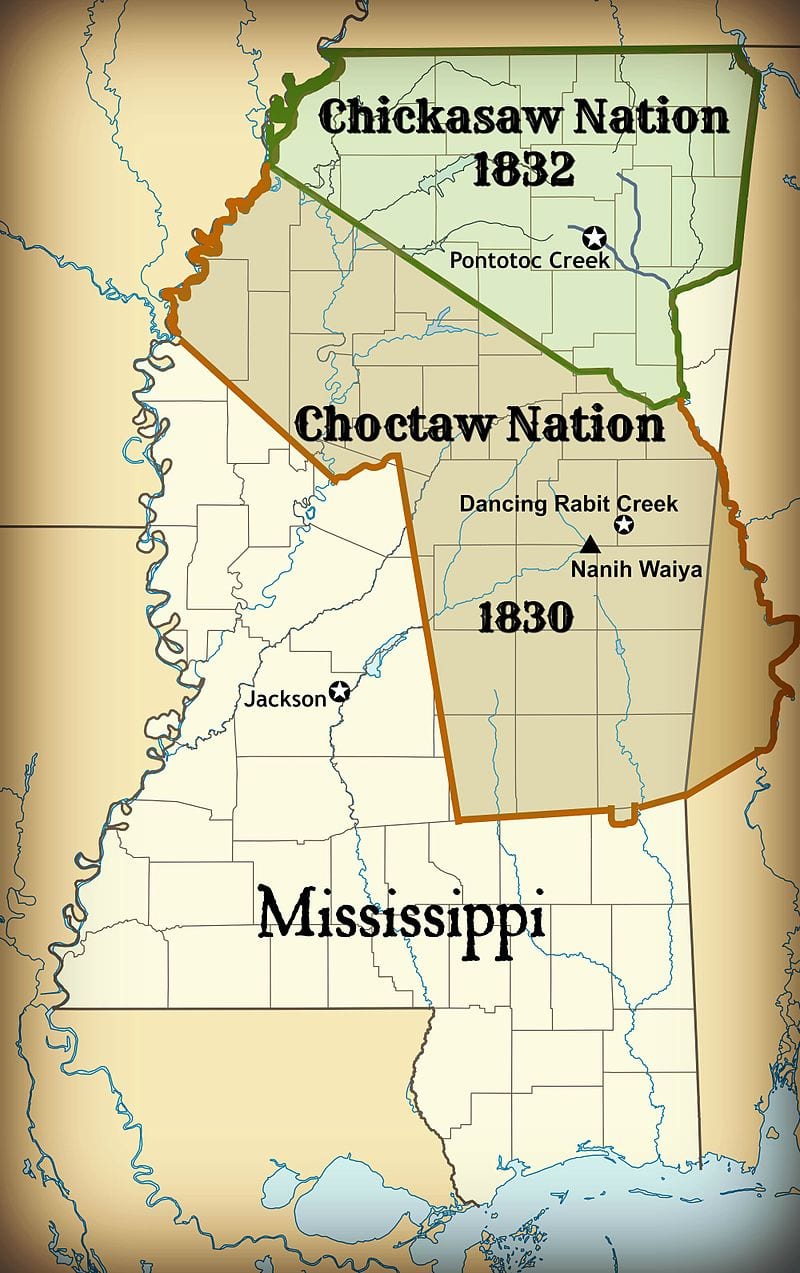

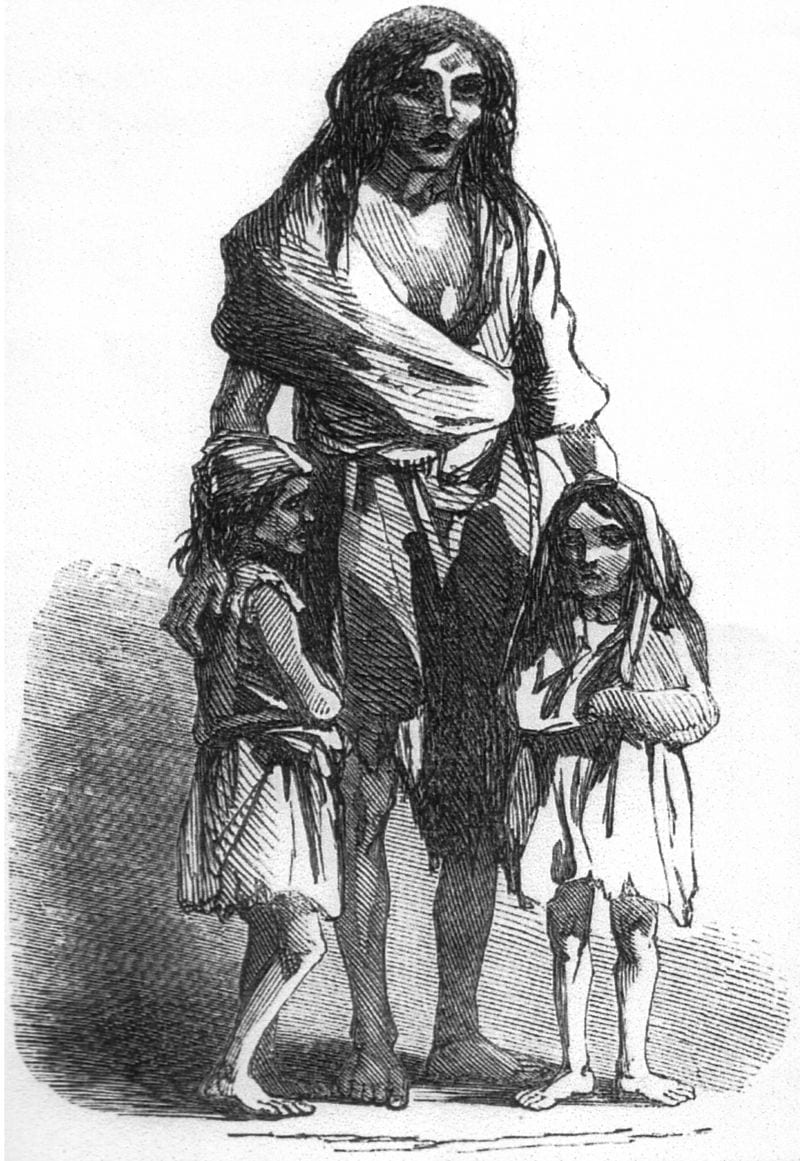

Even so, I doubt it will surprise you to learn that in the mid-to-late 19th century, the Choctaw people were struggling in every sense of the word.

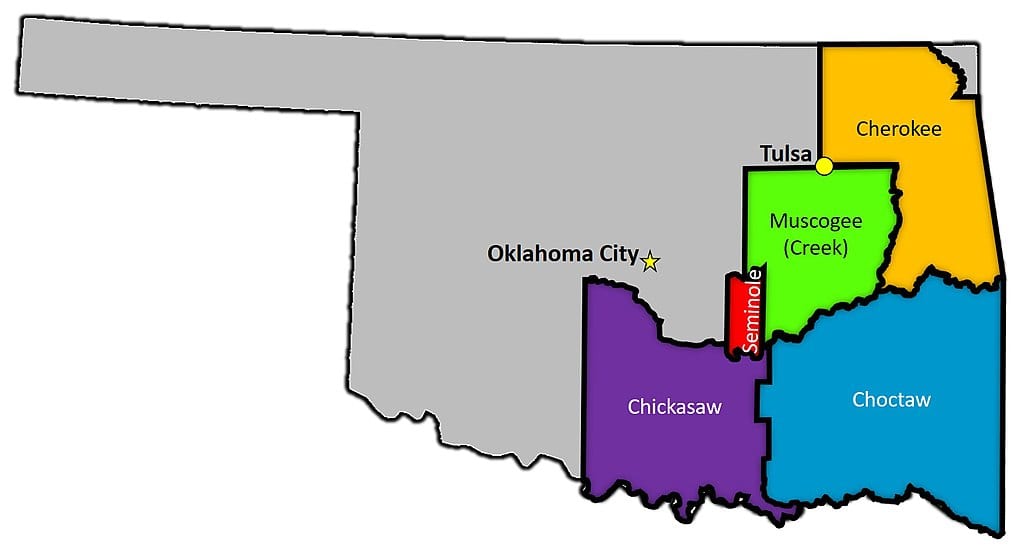

Their ancestral lands in Mississippi had been confiscated, and the remaining members of the tribe had been given the choice of remaining as U.S. citizens or moving thousands of miles to Oklahoma.

On the trek west, up to 25% of their nation died. Once they arrived, troubles waited there, too, according to the 1849 account of one Choctaw man.

He recalled seeing their “habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields, and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered, and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died.”

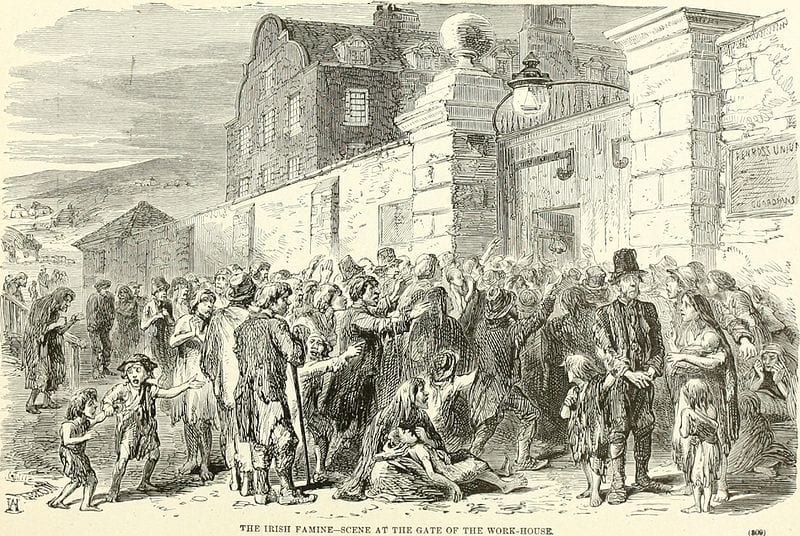

And still, when the stories about the Irish people, suffering through an incredible famine reached them, the tribe met and were moved to help.

By 1870, 2.5 million Irish people had immigrated to America to try to avoid the famine. The blight, and the ensuing famine, received extensive coverage in the American press. Papers were reporting that “a failure of the Irish potato crop was now too painfully certain,” and that “famine among the Irish people was apprehended.”

Reporting made it clear that the suffering and loss was tremendous, and that there was no end in sight. Appeals went out, urging help for the millions of people in Ireland who were within weeks of starving to death, and relief committees, charitable societies, churches, and synagogues all leapt to respond.

Donations came from all over, and in the end, around $550,000 were sent from the U.S. to Ireland.

No one expected a tribe like the Choctaw to come through.

They had little, had recently been evicted from their homelands, and even though the Trail of Tears was fading into history, members of their tribe were still arriving in Oklahoma on a regular basis – and all were worse for the wear, according to historian Anelise Hanson Shrout:

“Most would have experienced enormous financial, emotional, and demographic damage as a result of removal.

It is difficult to imagine a people less well-positioned to act philanthropically.”

No one knows exactly what was said in the meeting, or how a group of Choctaw Native Americans – along with a few agents, missionaries, and traders – managed to put to together $170 (well over $5,000 today).

The then-editor of the Choctaw newspaper Bishinik, Judy Allen, said the donation was “an amazing gesture. By today’s standards, it might be a million dollars.”

Most historians feel that their recent experience on the Trail of Tears, their own pain and suffering, moved them to do what they could to help others.

At the time, people figured their Christian evangelizing was working. Because of course they did.

The 1848 Report of the General Irish Relief Committee notes stated that,

“The largest part was contributed by the children of the forest, our red brethren of the Choctaw nation.

Even those distant men have felt the force of Christian example, and have given their cheerful aid in this good cause, though they are separated from you by many miles of land and an ocean’s breadth.”

An editorial in the Arkansas Intelligencer said simply,

“What an agreeable reflection it must give to the Christian and the philanthropist to witness this evidence of civilization and Christian spirit existing among our red neighbors.”

I’m not even going to get into everything that’s wrong with that, but the aid turned out to be both timely and necessary – it was another five years before the potato famine finally came to an end.

The Choctaw, one could argue, are still fighting for their just place in this country that once belonged to them, at least partially. They fought (and lost) on the Confederate side of the Civil War (they had been promised a state of their own), and after that, continued to struggle with cultural isolation, bullying, underemployment, and a continued lack of political representation.

Things have improved slightly since the establishment of their own tribal government in 1984, though many of their rights remain unclaimed.

Image Credit: Gavin Sheridan

The Irish people have never forgotten the generosity from across the pond, and of the Choctaw people in particular. In 2018, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar announced an Irish scholarship program for Choctaw Youth, addressing the nation directly in a statement:

“A few years ago, on a visit to Ireland, a representative of the Choctaw Nation called your support for us ‘a sacred memory.’

It is that and more. It is a sacred bond, which has joined our people’s together for all time.

Your act of kindness has never been, and never will be, forgotten in Ireland.”

Stories of people helping people, the kind that give you the warm fuzzies, don’t come around every day – especially these days.

Let’s all just sit and bask in it for a minute, shall we?