For me, the best parts of history are the little oddities that your history teacher doesn’t have the time to teach you. One of those, at least for me, was noticing the woman’s name at the very bottom of the Declaration of Independence.

Mary Katharine Goddard.

Who was she? Why was her name there? If your curiosity is piqued the way mine was, then read on because I’ve got the answers for you.

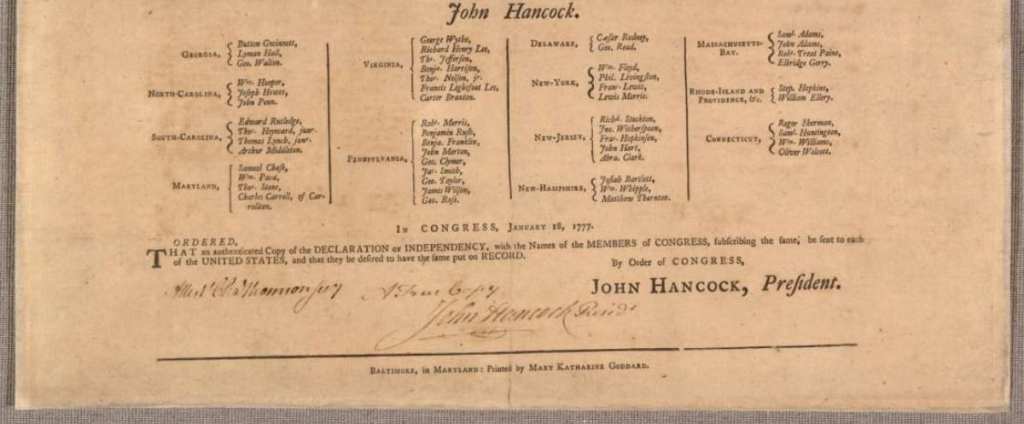

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Mary Katharine Goddard was one of America’s first publishers, as well as the colonies’ first female postmaster. She ran the Baltimore Post Office as well as a Baltimore-based newspaper. She also played a significant but often overlooked role in the American Revolution by printing articles about battles and facilitating important correspondence.

If you’ve read The Maryland Journal or the Baltimore Advertiser, her name might sound familiar to you. She began printing her name at the bottom of articles — as M.K. Goddard — after her brother and business partner skipped town. But it wasn’t until Congress asked her to print copies of the Declaration of Independence in 1777 that she made her way into the history books.

The text at the very bottom of the document reads: Baltimore, in Maryland: Printed by Mary Katharine Goddard.

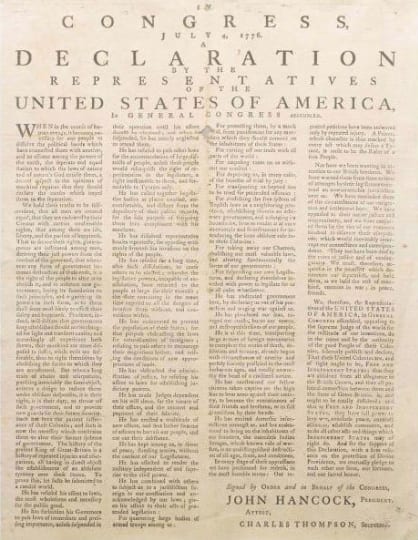

Image Credit: Public Domain

The copy she printed was the first to include the full list of founders’ signatures, and is the one that endures to this day. No one knows why she printed her full name on the document before running copies, but historians at the New York Public Library ventured a guess:

“Perhaps Goddard was trying to secure her place in the story of the nation’s founding. We can only speculate.”

Her story, sadly, ends the way too many women’s did back in the days of the Revolution — in obscurity. When her brother returned and resumed authority over the newspaper, he removed her name from the bottom. Five years later, she was pushed out of the postmaster general position by Samuel Osgood, who argued that a woman didn’t have the stamina for the position.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

For what it’s worth, more than 200 people in Baltimore signed a position demanding her reinstatement, but to no avail. Instead, she lived out her days running a bookstore, and died in 1816.

I’d argue that she still got prime placement in the annals of American history though — right at the bottom of the nation’s most important founding document.