Many people attempt to summit Mount Everest, and most of them make it to the top. Unfortunately, due to the myriad hazards of the journey – fatigue, confusion, lack of oxygen, natural disasters, falls, cold – there are more than a few who never make it off the mountain.

One of those unfortunate climbers was a woman named Hannelore Schmatz – not the first woman to summit Everest (though she did make it up), but the first woman (and the first German) to die there.

Hannelore and her husband, Gerhard, were experienced climbers when they decided to try their luck at conquering the world’s tallest mountain in the fall of 1979. The pair celebrated after reaching the summit (Gerhard, 50, was the oldest man to ever do it, at the time), then headed back toward base camp with their group. It contained 8 climbers and 5 sherpas, and while 6 of the climbers and all of the sherpas made it safely down, Hannelore and a Swiss-American man named Ray Genet did not.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Despite being an experienced climber, Hannelore and Genet were too tired to keep going and, despite warnings from a Sherpa about the dangers of remaining in the mountain’s “Death Zone” overnight, set up a bivouac camp. One Sherpa remained with them. The brutal snowstorm that occurred overnight was too much for Genet, who died from hypothermia before morning.

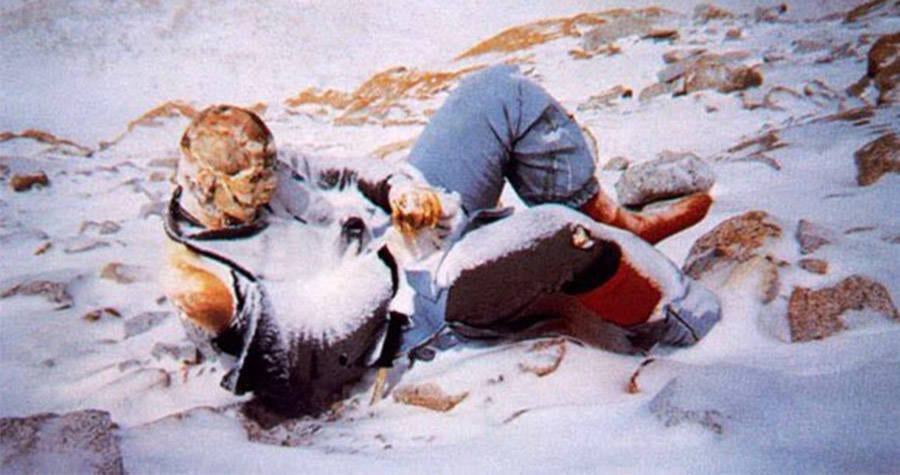

Schmatz and the Sherpa survived the night, and continued down the mountain. At 27,200 feet, she sat down to rest against her backpack. She fell asleep and never woke up. Her Sherpa companion stayed with her body, costing him most of his fingers and toes. He later reported that her last words were “water, water.”

The fatigue she experienced is a common cause of death on Everest, where the air is so thin that the lack of oxygen can cause poor coordination, confusion, and incoherence that can make even an experienced climber like Hannelore make decisions that they never would have otherwise.

She died from exposure and exhaustion just over 300 feet from Camp IV, the highest camp on one of the primary trekking routes.

Image Credit: YouTube

One attempt was made to recover her body in 1984, but a Sherpa and a Nepalese police inspector on the trek fell to their deaths, and it was decided that perhaps Schmatz wanted to stay where she was. Which she did, frozen in place with her eyes open and her hair fluttering in the wind, as other climbers hiked past on their way to the summit.

In the end, the mountain took her, a gust of wind blowing her body over the side of the Kangshung Face.

A fitting burial, perhaps, for a brave, talented woman who tackled one of the world’s biggest obstacles before succumbing to her own humanity mere feet from safety.

If you want to climb (or to attempt to climb) Mount Everest, you’d better hurry. Her glaciers are quickly disappearing in the face of the warming climates.