On the evening of April 25, 1986, in then Soviet Ukraine, Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant’s reactor number four exploded. The accident, which happened during a test, released over 400 times more radiation than what was discharged at Hiroshima, Japan, by atomic bomb at the end of WWII.

Photo Credit: Jason Minshull, Public domain

Dozens of people lost their lives and many more were hospitalized with radiation burns. Millions of people throughout Ukraine, Belarus and Russia were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation.

The power plant was reduced to rubble; the surrounding land scorched. Thousands of residents were forced to evacuate, never to return. The loss of life and health was devastating.

The images that emerged–unforgettable.

The Soviet military set up the Exclusion Zone that still exists today.

It is a roughly 18-mile circle around the plant, largely uninhabited due to the high amounts of detectable radiation. The area draws tourists curious about its history and how it looks today.

Photo Credit: Alexander Blecher, Creative Commons

The remains of the stricken reactor were covered with a “sarcophagus” or Object Shelter to prevent the further spread of radioactive material.

Another shelter on top of that called Chernobyl New Safe Confinement was installed by an international team in 2017. A monument sits in front of that.

Photo Credit: Flickr

The town of Pripyat, adjacent to the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, was not evacuated until almost midnight of April 26.

No one in an official capacity wanted to take responsibility for declaring the incident a disaster or call for a total evacuation of citizens. Children went to school while everyone else went about their day not knowing their town was officially radioactive.

Photo Credit: Pxhere

Opened in 1970 as the model communist village, Pripyat is deserted, although tourists and workers can visit for a few hours per day.

Before the disaster, Pripyat was a youthful city of 50,000. The average age of its residents was 26.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Nature has taken over the Exclusion Zone.

With few human beings around, plants and wildlife, like bears, bison and wolves, are reclaiming the territory.

Photo Credit: Picryl

All tourists, guides and workers must get measured for radiation before leaving the Exclusion Zone.

If levels are too high, then clothes must be left behind for disposal.

Photo Credit: Flickr

Over 600,000 responders, both civilian and military have been awarded honorary status of “Chernobyl liquidators” since the explosion.

Reservists weren’t given proper uniforms so they made their own with thick lead sheets protecting their spines and bones. Still, many suffered serious health problems–some deadly.

Photo Credit: Pexels

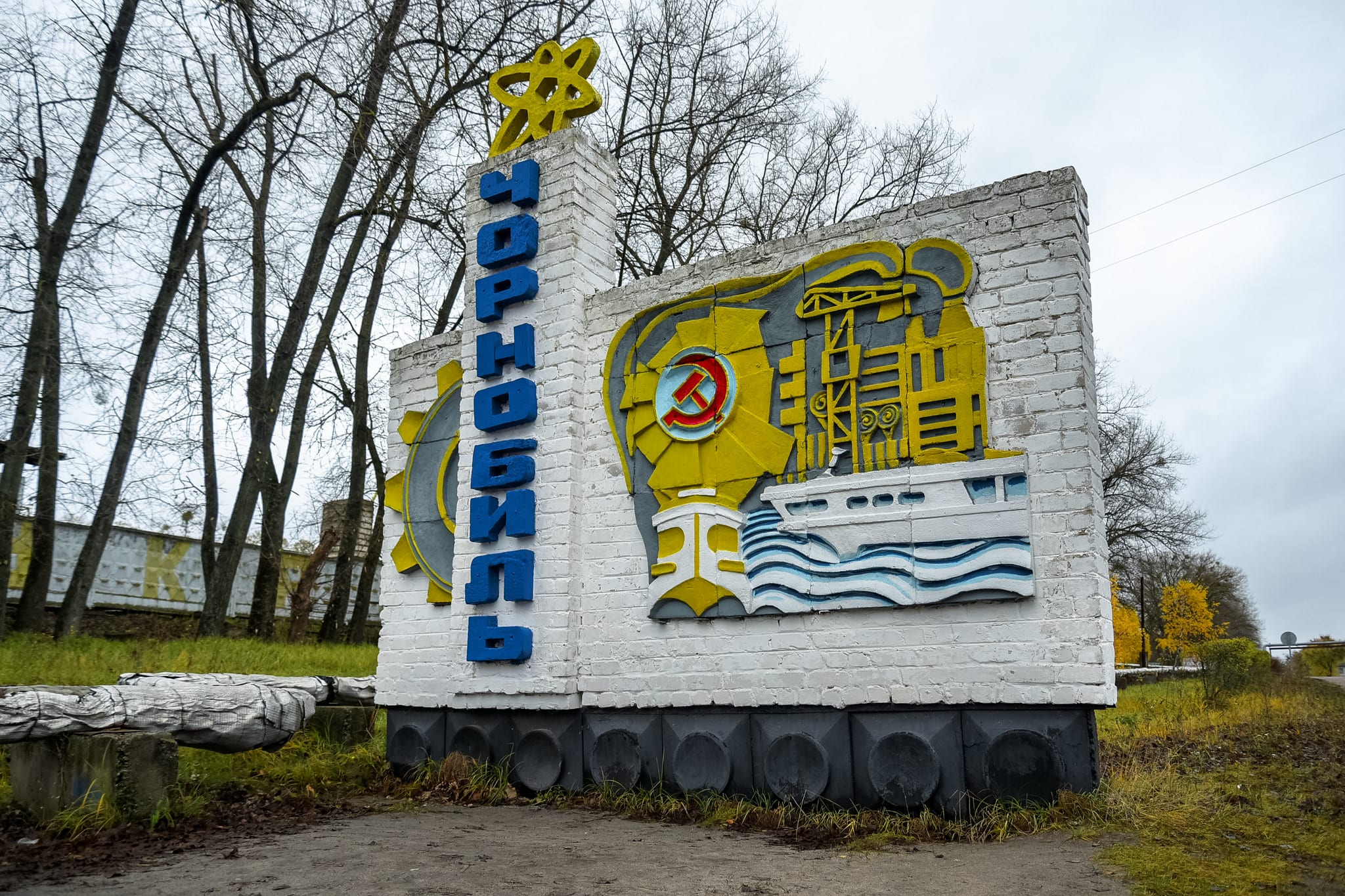

With permission, you can join a tour group and spend a few hours exploring pre-1991 CCCP.

See hammers and sickles, symbols of the former Soviet Union, as well as a statue of Lenin – non-existent in the rest of Ukraine.

Photo Credit: Flickr

The future of this site is up in the air. It is now part of Ukraine, and the country is showing interest in using the site for dumping its own nuclear waste.

Some would like to see the area become a nature preserve for the abundant wildlife already making themselves at home.

Whatever its future, Chernobyl’s radioactivity is expected to remain at hazardous levels for the next several centuries…so humans won’t be moving back permanently any time soon.