Pretty much everyone is stressed these days. It’s understandable; with the advent of social media and the 24-hour news cycle, we barely get a break from being inundated with information. Millennials can’t even imagine how much less stimulating it would have been to be alive 50 years ago because we’ve been stimulated to the gills since we were teenagers. All that stimulation at some point stops being just information inflow, and starts to be processed as stress – it’s just too much. It’s no wonder chronic stress and anxiety are reaching epidemic levels in the population.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

People aren’t meant to be constantly overwhelmed this way. We need time for our brains to relax – not only to feel better psychologically (although definitely to feel better psychologically), but also because stress is not just a feeling. Stress is biological in origin, and while occasional stress can be useful, the physiological factors behind stress are, when extended over long periods of time, actually harmful to your brain.

In fact, chronic stress can affect your brain’s size, structure, overall functionality, and even your epigenome – so pretty much everything about it.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

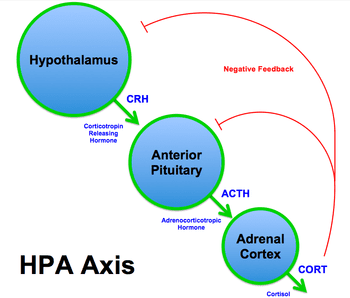

Let’s begin from the beginning. Stress starts with your hypothalamus, a portion of your brain that connects with your adrenal and pituitary systems. Together, they create the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis). Part of the HPA axis’ job is to react to stress-inducing situations. When you’re about to speak in public, it floods your body with cortisol, aka the stress hormone.

Photo Credit: BrianMSweis, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cortisol is great in certain situations – evolutionarily speaking, it jumpstarts your fight or flight reflex. If you’re walking in the woods, and you run into a bear, you definitely want that cortisol pumping. Even if you just need to focus on a test, moderate levels of cortisol are gonna get you to peak performance.

But when your cortisol levels rise because work is tough, and work doesn’t ever really quit being tough, so your cortisol levels stay elevated…then you’ve got a problem.

Photo Credit: iStock

Chronic stress increases function in the amygdala, the part of the brain that handles fear reaction, which leads to higher anxiety levels. It also decreases function in the hippocampus, a part of the brain that has to do with cognitive processes like memory, learning, and – crucially – controlling the HPA axis. So as activity in the hippocampus decreases in amount and in quality, it becomes harder to remember, harder to learn, and also harder to stop feeling stressed.

Long term exposure to cortisol also inhibits the creation of new brain cells in the hippocampus, so all those important functions the hippocampus controls are even more at risk. There is even evidence that this feedback loop is a risk factor for depression – and also Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

After long enough, chronic stress can also actually cause shrinkage of your brain – it starts to erode the connections between your neurons, called synapses, and decreases the size of your pre-frontal cortex, which is primarily responsible for self-control. So in addition to making it harder chemically speaking to stop feeling stressed (that hippocampus interaction from above), it is also harder to stop feeling stressed because now your decision making is being eroded, so suddenly it’s no longer as straightforward to just remove yourself from a stressful situation or reframe your perspective.

And if all this isn’t disturbing enough, there is evidence that long term exposure to cortisol because of chronic stress can alter your epigenome – how your genes are expressed – in a way that can be passed down to your kids. Very basically, everyone’s DNA has some genes that are on, and other that are off. This on/off binary isn’t always permanent, however, and stress is one thing that can change how genes are expressed. The study was done on mice, so there is that to consider, but the results showed the chronic exposure to stress hormones caused changes in gene expression that predispose them to be more stressed – meaning that long term stress may lead to heritable long term stress.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Luckily for the stressed among us, there are a few proven techniques you can use to fight back. The best ways to reverse the effects of cortisol on the brain are…exercise and meditation. 30-40 minutes a day of moderate exercise (even just walking) actively decreases the body’s levels of the stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline. Exercise also releases endorphins, neurochemicals that cause mood elevation (they make you feel good).

Short, regular meditation sessions also decrease stress, though it does take some effort at first. Both regular exercise and regular meditation can also increase the size and functionality of your hippocampus, reversing some of the harmful symptoms of chronic cortisol exposure.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

The other piece of advice regularly given to the stressed: make sure you get enough sleep. Sleep is really valuable for a healthy brain – though that’s another story – and in the fight against stress, we need all the help we can get.