There’s nothing new under the sun, and the press loving a titillating expose about a famous person certainly falls in line. As far back as the Roman Empire, writers were penning books revealing all of the rumors and secrets behind palace doors – people just love to read about famous people’s kinks and quirks.

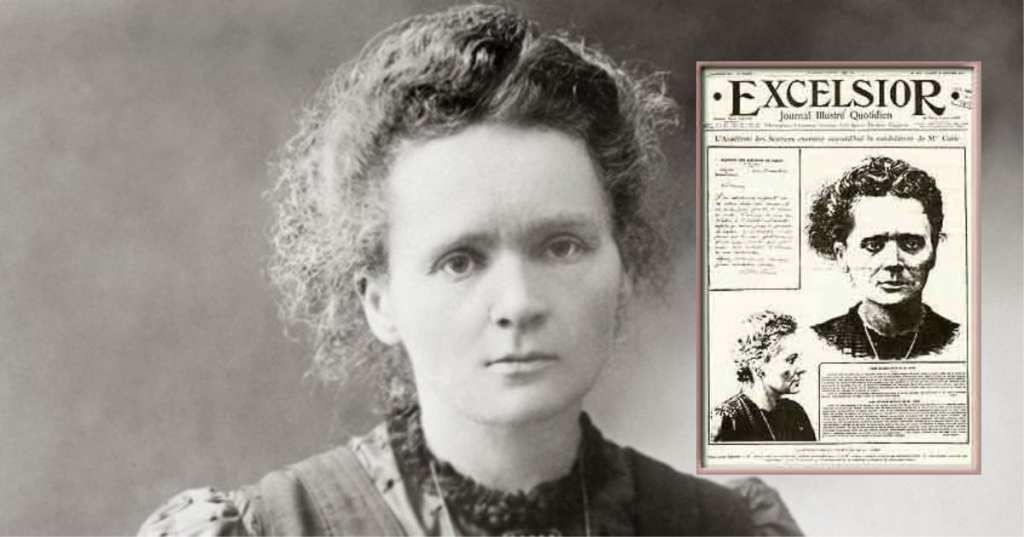

You’ve probably never thought about Marie Curie as anything other than a scientific genius, discoverer of radium and polonium, and two-time Nobel Prize winner, but that’s only because your high school history teachers only relay that sort of important-but-boring information.

If your history class was being taught by a reporter from TMZ, you would have heard about how, in 1911, the Polish born mother and scientist found herself smack dab in the middle of a sex scandal.

Her husband, Pierre Curie, had perished in a carriage accident in 1906. Marie had taken up with one of his former students, a married physicist named Paul Langevin. They were holed up in a Paris love nest when his wife had one of those feelings and hired an investigator to break in and steal letters that ended up being incriminated.

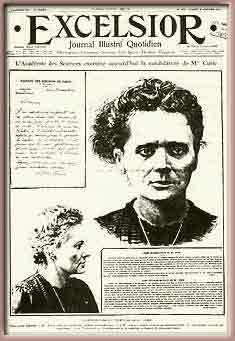

They leaked them to the press, and the French newspapers could not get enough. Xenophobia ran high at the time and they painted her as not only a home-wrecker, but a Jew (she wasn’t), and things got quickly out of hand. When she returned home from a conference in Belgium to find her home surrounded by an angry mob, she packed her daughters and fled to a friend’s.

Langevin was keen to defend his lover’s honor. He challenged one of the newspaper’s editors to a duel, though no shots were fired at their meeting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QlUw1k0ItE

Albert Einstein weighed in, arguing that Curie “has a sparkling intelligence, but despite her passionate nature, she is not attractive enough to represent a threat to anyone.”

That same year, at the height of the scandal, Marie won her second Nobel Prize. She attended the ceremony even though the committee suggested she skip it. Through it all, she remained dedicated to science, and eventually the whole melee died down.

She died in 1934, succumbing to illnesses caused by her continued exposure to radioactive materials. Almost 100 years later, her notebooks and other belongings are too radioactive to touch – and scientists estimate that will be the case for another 1500 years.

Personally, I think she would appreciate us remembering her entire life, and not just the work that she lived and died for. Telling stories like this one are important reminders that people are humans, as well as historical figures, and that even though she contributed enormously to science, she was also a woman.

More history teachers should get on board, I swear.