Baseball had Jackie Robinson, hockey had Willie O’Ree – black men who broke the color barriers in their respective sports and blazed a path for other minorities to follow and integrate what was previously a white man’s game. They endured taunts and threats of violence and changed their respective sports forever. But perhaps the most fascinating character to challenge American society through sports was heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

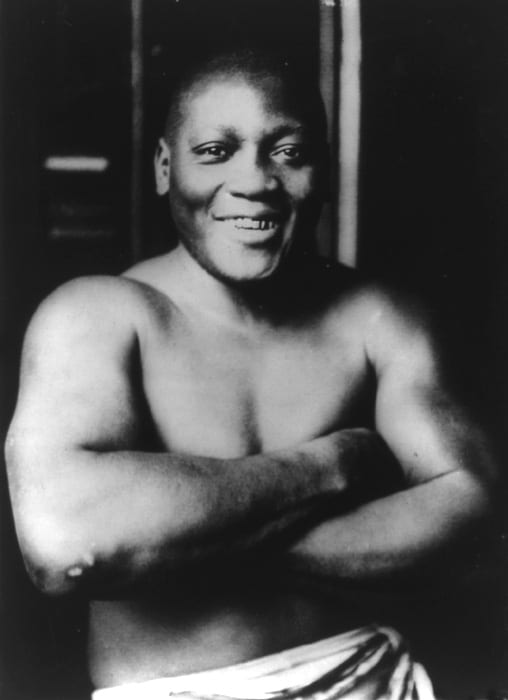

Johnson was born in 1878 in Galveston, Texas to parents who were former slaves. Johnson worked a series of menial jobs in his teens, but soon found he had no interest in a life of manual labor. The hulking youngster discovered he was exceptionally good at one thing – so good that perhaps he wouldn’t need to work on the docks. That one thing? Fighting.

Johnson got his start brawling in back alleys and barrooms before he was taken under the wing of a man he worked with, Walter Lewis. Johnson credited Lewis with training him in the finer points of boxing.

Johnson’s professional boxing career began in 1898 with a knockout victory. He fought and rose through the ranks steadily until a twist of fate changed his boxing career a few years later. On February 25, 1901, Johnson fought and was knocked out by Joe Choynski during a match in his hometown of Galveston. Prizefighting was illegal in Texas at the time, and Johnson and Choynski were both arrested and thrown in jail, but since the sheriff was a boxing fan, he allowed the men to spar in the prison yard. The boxers were released 23 days later.

Johnson credited his time in jail as a turning point in his career, later stating that his training with Choynski made him a much better boxer.

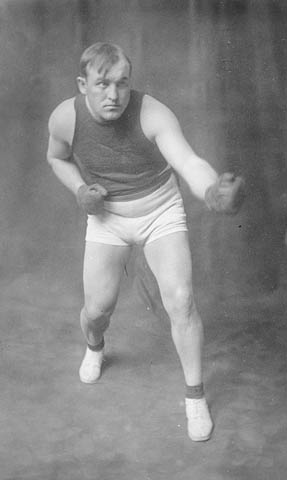

Johnson continued his ascent in the boxing world and won the black heavyweight title in 1903. Like in other sports of the time, there was an unofficial color barrier in boxing that kept black heavyweights from squaring off against white fighters. Champions such as John L. Sullivan, James Corbett, and Bob Fitzsimmons all refused to fight against black boxers. Like other heavyweight champs before him, Jim Jeffries retired upon declaring that there were no remaining challengers – without facing Johnson or any other black fighters.

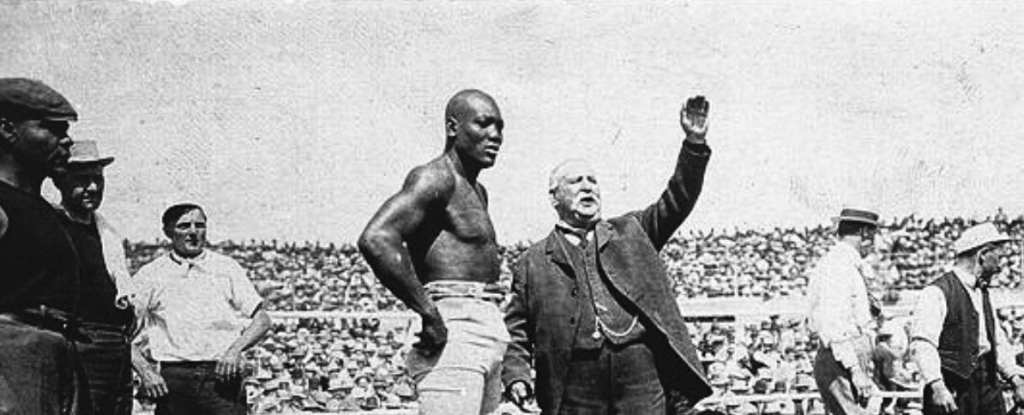

Jeffries’ retirement left the championship vacant, and Tommy Burns, who hailed from Canada, won the heavyweight title. Burns finally agreed to fight Jack Johnson in December 1908 after a promoter agreed to pay Burns $30,000 for the bout. The fight was a one-sided affair, and Johnson left the ring as the first black heavyweight champion.

Many white boxing fans were furious about a black man holding the championship belt and called for a “Great White Hope” to reclaim the title.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Johnson was reviled by white fight fans not only because he was black, but because he was outspoken and didn’t have any regard for what people thought of his actions. Johnson dressed well, drove fancy cars, and was regularly seen with white women – in fact, he had three white wives during his life, which was a major taboo at the time. Details of his lifestyle were splashed all over newspapers and tabloids. Inside the ring, Johnson often taunted and toyed with his opponents, further drawing the ire of crowds.

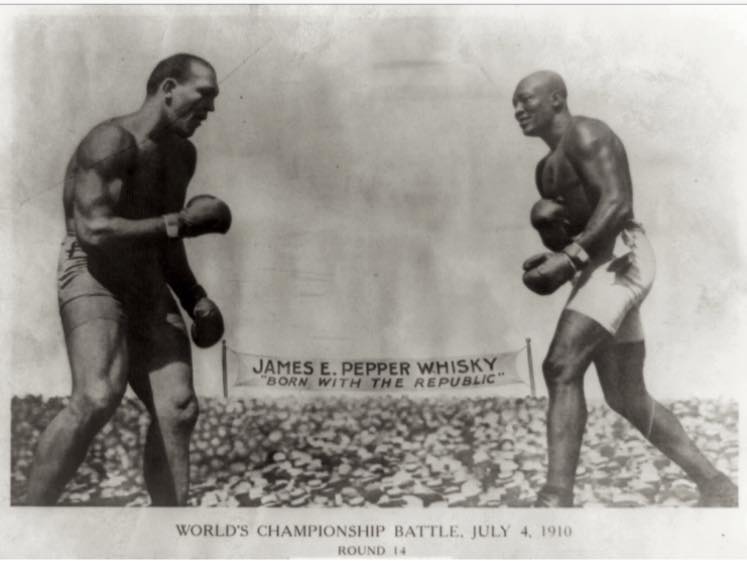

Former heavyweight champion Jim Jeffries believed he was the “Great White Hope” who could take the championship away from Johnson, and he came out of retirement to prove it. The bout took place on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada and was billed as the “Fight of the Century.” Yet Jeffries was not the fighter he thought he was – Johnson handled the former champ with ease, and Jeffries threw in the towel in the 15th round after he had been knocked down twice. Jeffries said after the fight, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

Photo Credit: Facebook, Nonpareil clothing

White people were angry at the outcome and blacks were jubilant, which led to even more animosity. Race riots broke out in several cities, including New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Houston. At least 20 people were killed in the unrest. Film footage of the fight was banned from being shown in some cities. Teddy Roosevelt said of the fight film, “The last contest provoked a very unfortunate display of race antagonism… and it would be an admirable thing if some method could be devised to stop the exhibition of the moving pictures taken thereof.”

Photo Credit: Facebook, I Love Being Black

Johnson defended his title for years before eventually losing the heavyweight championship in 1915, but it was his life outside the ring that created headlines. Johnson’s first wife committed suicide in 1912, and he was seen with an 18-year-old white woman named Lucille Cameron on his arm only weeks after his wife’s death. Cameron had allegedly previously worked as a prostitute and authorities decided to zero in on Johnson, who had paid for Cameron to come from out of state to work in his cafe. Police arrested Johnson and charged him with violating the Mann Act, which made transporting women across state lines for “immoral purposes” illegal.

Newspapers jumped on the story and Johnson was vilified in the press as an evil brute. The case eventually fell apart, but Johnson was arrested again for violating the Mann Act; this time he was convicted (by an all-white jury) in June 1913 and sentenced to a year and a day in prison. Johnson skipped bail and fled the country. He lived in exile for the next 7 years, spending time in Europe, South America, and Mexico. He finally returned to the U.S. in 1920, surrendered, and was sent to Leavenworth Prison in Kansas to serve his sentence.

Johnson continued to box after his prison release, but he would never again recapture the glory of his earlier years. In fact, he fought professionally until he was 60 years old, but he lost 7 of his last 9 pro bouts. On June 10, 1946, Johnson died in a car accident in North Carolina after angrily driving away from a diner that refused to serve him.

Johnson’s life was not always pleasant, but there is no doubt the man lived on his own terms, refusing to take sitting down the garbage society tried to pile on him.