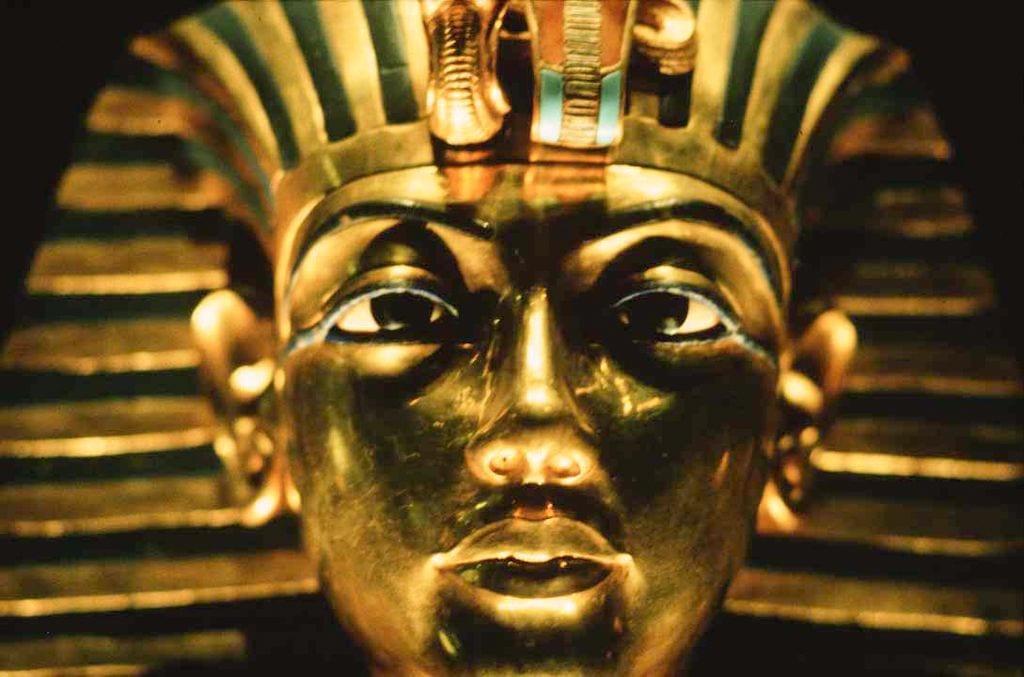

King Tut, or Tutankhamun, was a boy king of Egypt, reigning from 1332 until 1323 BC. He was only 10 years old when he became Pharaoh. His young age and short reign are notable enough, but he is most famous for his tomb, which was opened in 1922 and found filled with gold and extraordinary Egyptian artifacts.

Photo Credit: Steve Evans, CC BY 2.0

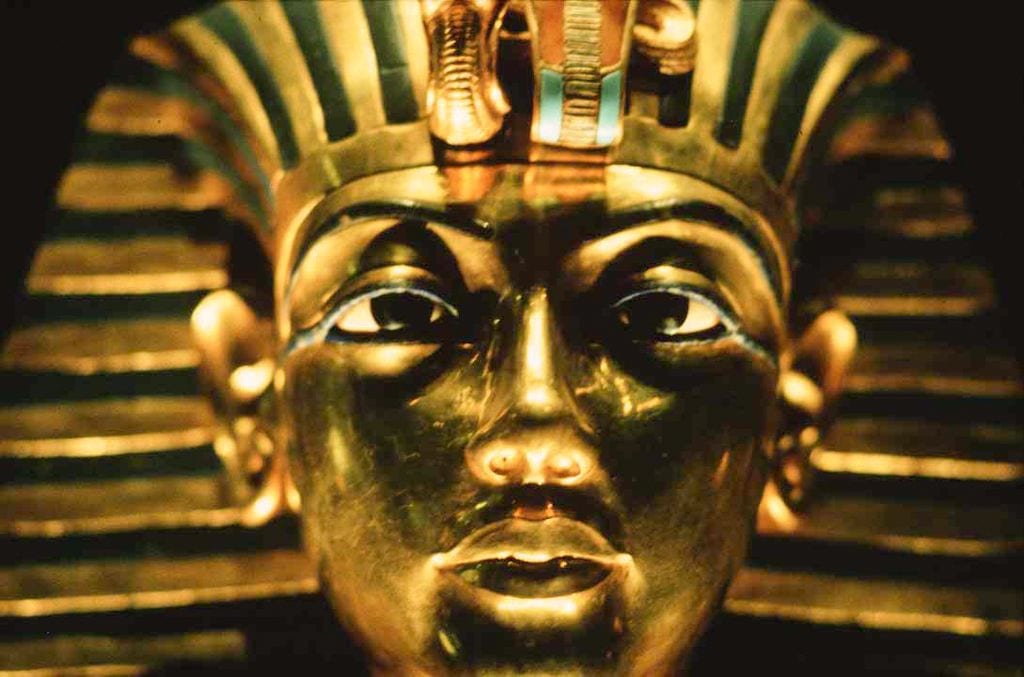

When archeologist Howard Carter and his team opened the tomb of King Tut in 1922, those fascinated with Egyptology knew of the legends of curses and so watched for King Tut’s curse to extend its undead hands. The tomb had been left alone about for over 3,000 years – certainly, it was consecrated and should remain undisturbed.

And terrible events threatened those who dared to enter.

Photo Credit: Flickr

For the next 10 years, the dying didn’t stop.

Carter’s team was financed by a wealthy man named George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon. After receiving a cable from Carter announcing that after six years of exploration he had found the tomb of King Tut, Lord Carnarvon rushed to the area in Egypt known as the Valley of the Kings. He had dreamed of this moment for years and was a witness when Carter finally broke the seals and opened the door to the Pharaoh’s final resting place.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

When Carter pulled the door back, Carnarvon asked, ” Can you see anything?” Carter answered, “Yes. Wonderful things. Wonderful things!”

A few weeks later, as he was shaving, Carnarvon cut his face where a mosquito had bitten him. He consequently died of blood poisoning. Supposedly, the lights in his home back in England went out at his last breath, and a gash on the cheek of the king’s mummy matched the cut on Herbert’s.

The second ‘manifestation’ of the curse wasn’t a death, but it was terribly unlucky just the same. Carter sent a mummy’s hand paperweight to his friend, Sir Bruce Ingham, with a scarab bracelet inscribed with a warning: “Cursed be he who moves my body. To him shall come fire, water and pestilence.”

Photo Credit: Flickr

Carter, who scoffed at the notion of any curse, meant the gift as a macabre joke. But soon after receiving the mummy hand, Sir Ingham’s house burned to the ground, then flooded.

Ingham didn’t rebuild.

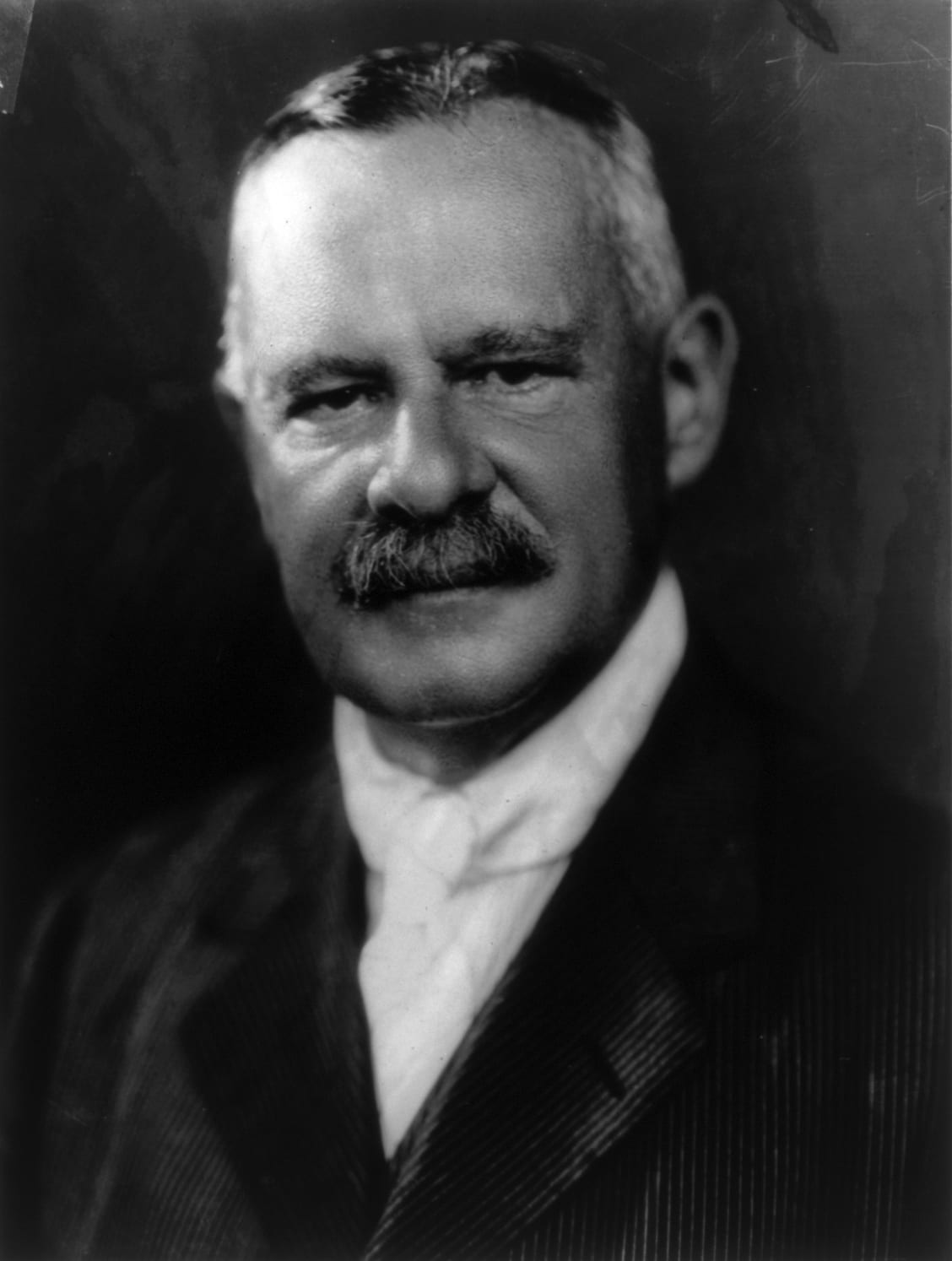

American financier and railroad executive George Jay Gould visited the tomb in 1923. He contracted pneumonia a few days later and never recovered, dying within the year.

George Jay Gould

Photo Credit: Public Domain

The curse also extended itself to people who never even went to the tomb. Carnarvon’s half-brother, Colonel The Honorable Aubrey Herbert went blind, had all this teeth pulled (he though it might cure his blindness) and died of sepsis – five months after Carnarvon.

Effigy of Colonel The Honorable Aubrey Herbert

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hugh Evelyn-White was one of the archeologists who helped excavate the tomb. It was rumored he was so spooked by the thought of a curse taking the lives of others associated with the project that he hanged himself. His suicide note, written in blood on a wall said, “I have succumbed to a curse which forces me to disappear.”

Also present at the opening of the tomb were American Egyptologist Aaron Ember and his wife, both of whom perished in a fire in their home after giving a dinner party. Though they initially escaped the flames, Ember and wife ran back in. She wanted to save their son. He wanted his manuscript–The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

In truth, out of the 58 people who were present when Carter opened the sealed tomb doors and discovered the riches within, eight died within 12 years. Carter himself lived to be 64 before dying of lymphoma.

So, which is it? Curse or coincidence?

Historians may be able to explain away the deaths and disasters due to the times and other circumstances. But the idea that there was a curse of King Tut’s tomb has been a boon to both tourism in Egypt and to Hollywood horror movie-making.

Curses are just more fun.