Trending Now

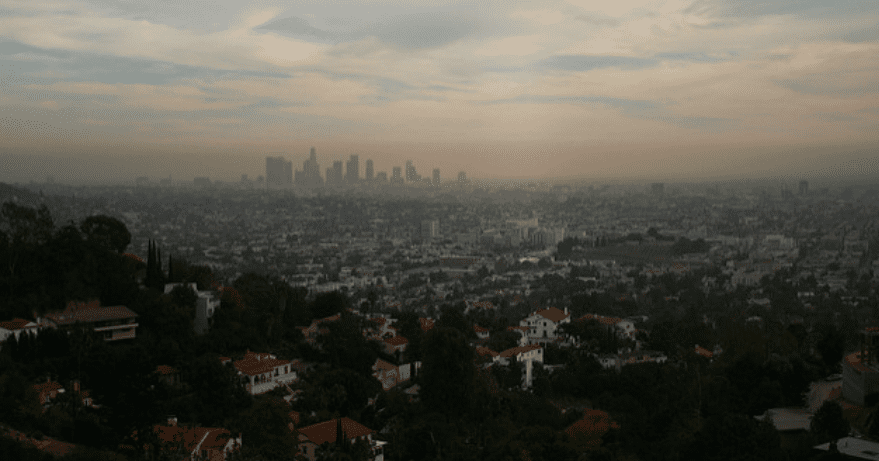

Inequality is rampant in our society, even down to the quality of air we breathe. It’s been common knowledge for a long time that minorities in the U.S. tend to live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than white Americans and that leads to a disparity in health outcomes along racial lines in this country.

A study that was recently published sheds new light on this problem in terms of consumption. It shows that air pollution in this country is disproportionately caused by white Americans’ consumption of services and goods, but the pollution is disproportionately inhaled by black and Hispanic Americans.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Anjum Hajat, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the research, said, “Inequity in exposure to air pollution is well documented, but this study brings in the consumption angle.”

The study took six years to complete and was led by professor Jason Hill of the University of Minnesota. The air pollution metric known as PM2.5 (particulate matter 2.5) is the most relevant way to measure how pollution affects human health. High levels of PM2.5 are linked to all kinds of health issues like birth defects and diabetes. This kind of pollution is mostly caused by humans, through burning fossil fuels or through agriculture.

Photo Credit: pxhere

The researchers made maps detailing where PM2.5 population was evident. Places like West Virginia and Pennsylvania had high PM2.5 pollution due to coal mining and areas such as Central California and the Midwest had high pollution caused by agriculture. The researchers then broke down areas by looking at their racial makeups, then the health effects on populations, and finally they looked at consumer spending in different regions to determine the main emitters of pollution based on consumption and who actually suffers from that pollution.

The study showed that white Americans are exposed to 17% less air pollution than they produce through consumption, while black Americans and Hispanics experience 56% and 63% more pollution, respectively, than is caused by their consumption.

Ana Diez Roux, another epidemiologist who was not involved in the study said, “These results, as striking as they are, aren’t really surprising. But it’s really interesting to see consumption patterns rigorously documented suggesting that minority communities are exposed to pollution that they bear less responsibility for.”

Photo Credit: Pixabay

She added, “If want to ameliorate this inequity, we may need to rethink how we build our cities and how they grow, our dependence on automobile transportation. These are hard things we have to consider.”

It’s fascinating how the team came to their conclusions!