You don’t have to be a historian or a scholar to realize that the end of the Vietnam War was a complete and utter confusing mess. I mean, even more so than the entire war, front to back. The U.S. was finished, they were trying to get out in a hurry, and Vietnam had descended into chaos in the process.

Just weeks before the fall of Saigon in 1975, the United States added another burden to their long list – the lives of over 2,500 children who were said to be orphaned and in need of help.

Operation Babylift saw planes full of children – infants to toddlers to those a bit older – come into processing centers in Washington and California. The number of dependents on the flights far outnumbered the adults charged with their care.

The flight attendants and others on the flights did their best to make the children comfortable with makeshift materials. Many of them were nestled in cardboard boxes, some were strapped into seatbelts or secured with cargo netting, while others lay strewn in the aisles on piles of blankets and towels.

Photo Credit: National Archives

One Pan Am flight attendant remembers the harrowing flight home and dodging “midget bodies crawling in the aisles”:

“We constantly peeked into bassinets to make sure each baby was still breathing. I froze as I flashed my light on each little back, waiting for what seemed like hours to see a ribcage move with the breath of life.”

A nurse on the flight was similarly traumatized by the entire experience, and claims that she couldn’t sleep the entire 30 hour flight. She was “overwhelmed” by the “endless flow of little ones flowing onto the plane filling every available space.”

Jim Trullinger had been conducting doctoral research in Vietnam before being forced to flee on one of the flights. He recalls that there were so many children on the plane that there was nowhere for him to sit. Not only that, but after one of the first Operation Babylift flights crashed weeks before, killing all aboard, including 78 children, he was expected to play his part in saving lives in the event of another catastrophe.

“Before takeoff, one of the flight attendants told me that if there was a crash, I was to get off the plane first and she would toss the babies to me.”

Once the planes arrived in the United States, the babies were off-loaded and triaged. Many of them were ill and required treatment for diseases like dehydration, intestinal illnesses, pneumonia, skin infections, and even things considered mundane in the U.S., like chicken pox.

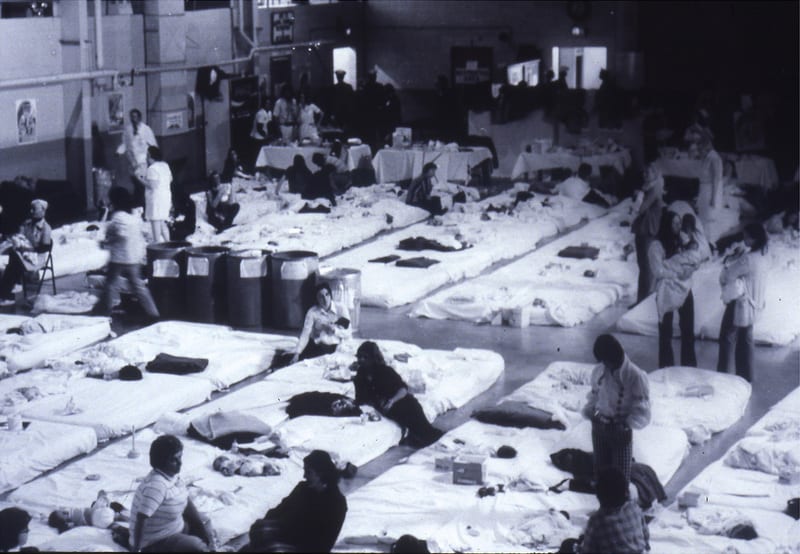

Around half of the children went through The Presidio in San Francisco, a military base that housed a huge, football field-sized building called Harmon Hall that was utilized as a care facility. There, they were under the care of Vietnam vets, nurses, and others who were all under the purview of a local philanthropist named Michael Howe.

The hall was crammed with small mattresses and layers of blankets for children to lay on, with half of the facility devoted to support services like feeding volunteers who worked around the clock. There were occasional reports of people who had been promised babies showing up and stealing them from The Presidio.

Photo Credit: Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives and Records Center

Howe’s first impressions of Harmon Hall and the mass influx of children was disbelief. He remembers thinking, “How did we do this? Did we really do this?”

It was a question that would take on darker tones in the days, weeks, and years to come as the orphan status of at least some of the children was called into question.

In an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, translator Jane Barton said the following about what she observed working with the children at Harmon Hall:

“There are unquestionably children in the airlift who are true orphans. But I talked to a number of children who said they are not orphans.”

Howe, too, claimed that he “felt it before we closed out our work. The word ‘felt’ is important – I had no proof.”

Photo Credit: Associated Press

It turned out that their thoughts and instincts were correct, as the legacy of Operation Babylift became more and more complicated over the years. Lawsuits have been filed on behalf of the children, including one brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights in 1975 that sought to reunite adoptees with living relatives in Vietnam. Some children have found biological family members and others continue to search.

Some have made the return trip to Vietnam, searching for a legacy and roots they believe were stolen from them by the well-meaning but panicked United States government. Did the U.S. save children, or did they steal them?

I think it’s possible that the answer is both, though that doesn’t make what happened any easier to swallow for those directly involved.