If you want my opinion, the next epidemic that threatens millions of lives isn’t going to be ebola or one of its truly terrible cousins. It’s going to be a twist on the annual flu.

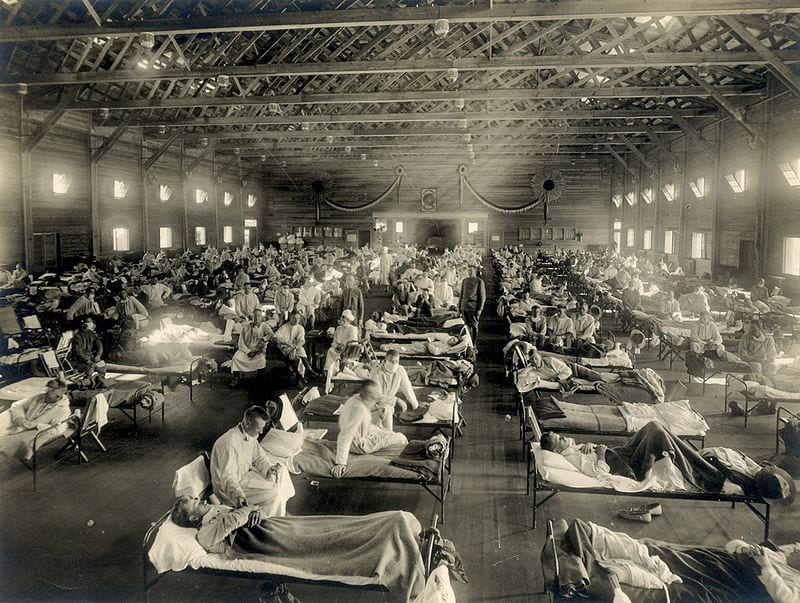

There’s precedent for this: in the early 20th century, the Spanish flu killed up to 100 million people across the globe. What’s even scarier is there’s no way to predict when another mutated flu virus will rear its ugly head.

“A major pandemic like the one we saw in 1918 has the potential to kill large numbers of people and shut down the world’s economy,” Michael Worobey, one of the two senior authors of a study on the subject, noted.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

What’s less apparent is who this future pandemic might spare, but scientists have recently unearthed an…unusual theory.

According to researchers from the University of Arizona in Tucson and the University of California, Los Angeles, the year you were born could have some influence on whether or not you survive the coming plague.

Up until now, it was believed that your previous exposure to a flu virus didn’t have any effect on your ability to recover from a new flu virus – particularly ones that can jump from animals into humans. However, when the team studied two avian-origin influenza A viruses, both of which have caused severe illness and death in humans, they discovered that the human influenza strain a person was exposed to during their first flu infection determines which new, avian flu strain they’ll be protected against in the future.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

They’re calling the effect “immunological imprinting.” It appears to be totally dependent on a person’s very first flu exposure – and it’s difficult to reverse or affect with immunizations.

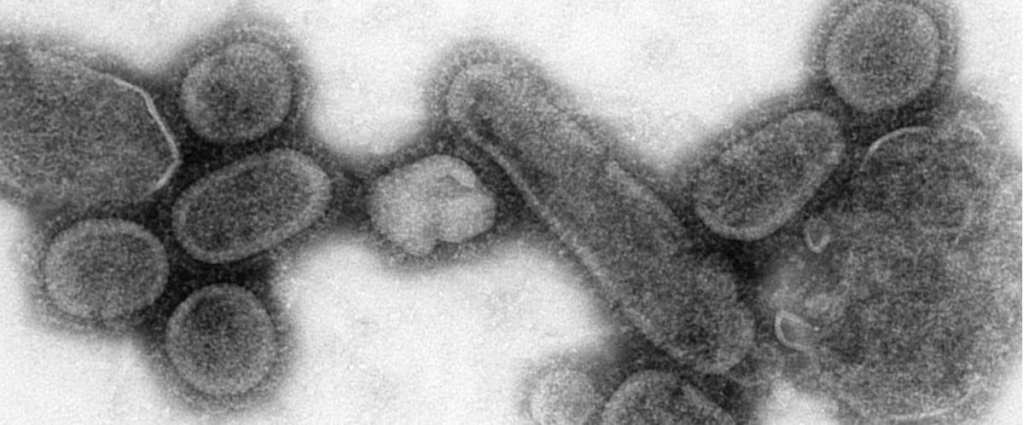

When a person is first exposed to a flu virus, the body makes antibodies that target hemagglutinin, a receptor protein that sticks out from the virus’ surface. And though there are 18 known influenza A hemagglutinin subtypes, there are only two main types.

So, if the first flu you were exposed to and the new virus are different subtypes but fall under the same main type, your immune system still recognizes it and provides you with enough protection to save your life. Pretty cool, huh?

Photo Credit: Pixabay

However, if the first flu you were exposed to and the new virus fall under opposite types, you aren’t likely to be as protected – or as lucky.

What’s worse, there’s no way to predict which of the 18 subtypes will jump from animals to humans next so there’s no way to predict which age groups might be most at risk when it does. But hey, a 50/50 shot’s better than nothing!

People born before the late 1960s were exposed to H1 and H2 as children and are particularly susceptible to H5 and H7 viruses, while people born after the 60s, who were exposed to H3 as children, show opposite predilections.

“If either of these viruses [H5 or H7] were to successfully jump from birds into humans, we now know something about the age groups that would be hit the hardest,” Worobey says.

The study’s authors believe that this evidence could explain why more young adults died from the Spanish flu than their older counterparts, says Worobey.

“When I was finishing up that work and looking at the age patterns, I noticed something interesting.

Those young adults were killed by an H1 virus, and from blood analyzed many decades later there is a pretty strong indication that those individuals had been exposed to a mismatched H3 as children and were therefore not protected against H1.”

Photo Credit: Pixabay

People who are matched with a new virus, hemagglutinin-ly speaking, show “a 75% protection rate against severe disease and an 80% protection rate against death.”

Worobey and the other authors of the study are hoping the information can eventually be used to create and tailor vaccines based on which flu strain imprinted on your immune system first. “Such a vaccine would likely target the same conserved protein motifs on the virus surface that underlie this age-specific pattern,” he explained.

“In a way it’s a good-news, bad-news story. It’s good news in the sense that we can now see the factor that really explains a big part of the story: Your first infection sets you up for either success or failure in a huge way, even against “novel” flu strains. The bad news is the very same imprinting that provides such great protection may be difficult to alter with vaccines.”

“A good universal vaccine should provide protection where you lack it most, but the epidemiological data suggest we may be locked into a strong protection against just half of the family tree of flu strains.”

No word on what this means for people who get hit with strains of influenza B, but either way, this imprinting sounds better than what was going on in Twilight.

Just saying.