Trending Now

Many in the history and medical fields feels as if we’re on the verge of our next major epidemic – akin to the Spanish flu, in terms of how many humans could lose their lives – but no one knows for sure what it will be or when it will show up.

If the 5 historical epidemics below are any indication, though, the next one is going to be bad.

#5. Saint-Domingue Yellow Fever Epidemic, 1802

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Between 30,000 and 55,000 people died in what is modern-day Haiti when Napoleon’s troops arrived to restore order on the island after a huge slave uprising. The troops began dropping like flies from yellow fever – a disease not present in France.

A fact that was not lost on the revolutionary leaders, one of whom wrote:

“Do not forget that while waiting for the rainy season, which will rid us of our enemies, we have only destruction and fire as weapons.”

The letter seems to suggest Louverture was aware that yellow fever would kill off the opposing soldiers, leaving them free to claim independence from France.

#4. Vatican Malaria Outbreak, 1623

Photo Credit: Public Domain

When 8 cardinals and 30 other church officials died from malaria, they may actually have ended up saving millions. Jesuit missionaries in South America observed indigenous people using the cinchona tree bark to treat shivering and fevers and shipped the “Peruvian bark” back to Rome.

Physicians there used it to successfully treat malaria, and in 1820, French chemists isolated quinine, the active antiprotozoal compound present in the bark, and the primary treatment for malaria for many, many years.

#3. Fijian Measles Outbreak, 1875

Photo Credit: Public Domain

More than 40,000 people died in 1875 after the Royal Navy ship HMS Dido returned Chief Cakobau to his people – and left the measles virus behind, too. The chief recovered but infected his sons, who in turn infected leaders from many surrounding islands.

Some Fijians felt the epidemic was a deliberate act on the part of the British and staged an armed rebellion. Partially because of the population decline, they failed, and British colonists seized Fijian property and brought in Indian indentured servants. Years later, when the Fijian people rose up again, they were joined by the Indians in their coup d’etat.

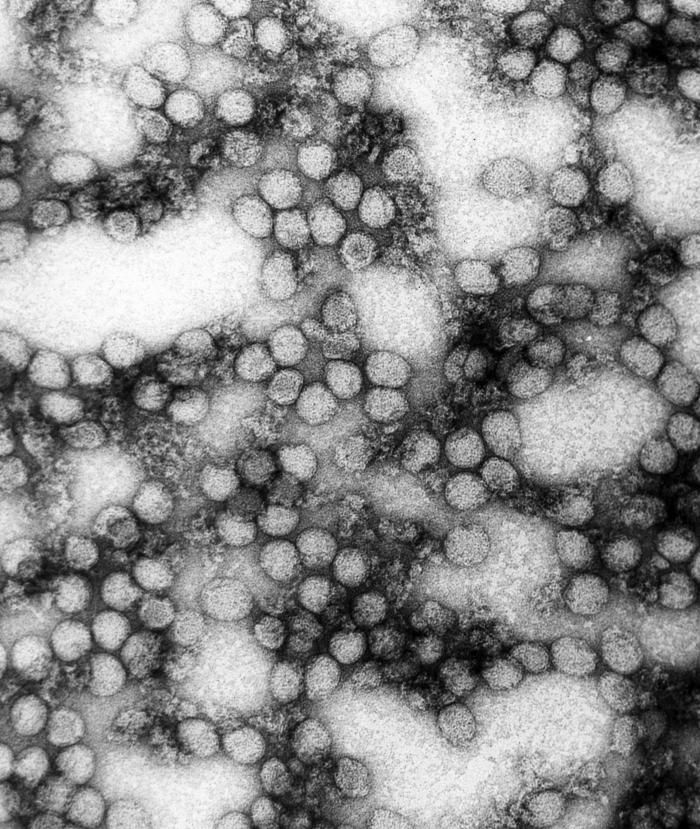

#2. New England Smallpox Epidemic, 1721

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Puritan minister Cotton Mather learned about the practice of inoculation against smallpox from one of his African slaves, but when smallpox hit Boston, many of the town’s citizens recoiled on religious grounds (sound familiar?). While one critic even threw a bomb into Mather’s home, physician Zabdiel Boylston believed him and inoculated his own son and hundreds of others.

At the end of the outbreak he evaluated his data and found that only 2% of his patients died, compared with almost 15% of those who were not inoculated against the disease. His results informed Edward Jenner’s experiments a few decades later.

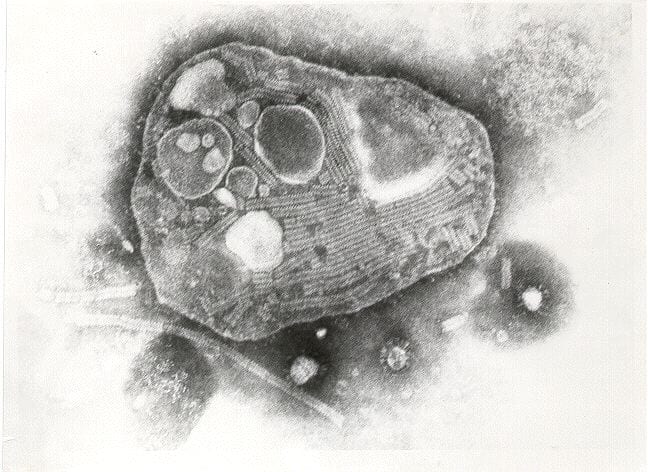

#1. African Rinderpest Outbreak, 1890

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Millions of cattle – and an unknown number of humans – died in Eastern Africa during what has been called “the most catastrophic natural disaster ever to affect Africa.” Rinderpest (which is a cattle disease and does not affect humans) and smallpox nearly destroyed the Maasai way of life, with the former killing up to 90% of infected cattle.

The loss of livestock caused the prices of the remaining cows to soar, disrupting the traditional means of agriculture and forcing African landowners to sell their property to survive. The social unrest allowed European colonialism to take hold and contributed to the Boer and Matabele Wars, and the decimation of the continent’s oxen made way for railway construction.

Rinderpest was declared officially eradicated in 2011 – the second disease, after smallpox, to be totally driven to extinction by humans.

I hope you’re all stocked up on canned goods and masks, my friends. It could get ugly.