Trending Now

The history of Africa’s Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) is tragic and violent, any way you slice it. The once blessedly forgotten corner of the continent was claimed by Leopold II of Belgium in order to exploit its rich rubber resources, and the lives of the people there would never be the same.

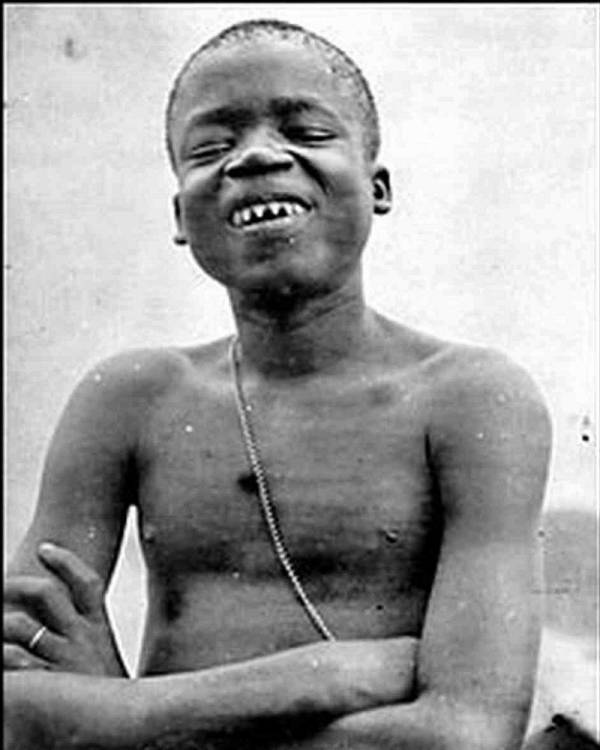

Prior to the Belgian occupation, Ota Benga was born into a tribe of Mbuti pygmies who populated the Ituri Forest in small family groups of 15-20 people. They moved with hunting opportunities and kept to themselves, and Ota Benga was poised to one day lead a band of his own.

But then the Belgians came.

Photo Credit: YouTube

Like many (most? all?) colonizing people, they were corrupt. They subjected the natives to rape and murder, beating them and severing limbs as punishment for not working fast or hard enough in the rubber factories. Wars erupted and mass deportations took place, Arab slavers invaded, and the place was dumped into a never-ending upheaval that, for Ota Benga, ended with the slaughter of his entire family.

Without them, he had nothing and no one, unless another family group would agree to adopt him.

Sadly, his life was about to get even worse.

He was captured by slave traders, slapped in chains, and dragged from the only home he had ever known to work in an agricultural village. There, in 1904, he was discovered by an amate*r explorer named Samuel Verner. Verner had been deployed to Africa under the guise of finding exhibits for the St. Louis World’s Fair that would educate the people on a perverse (read: racist) brand of anthropology. After getting a look at Benga’s dark skin, short stature, and teeth filed into points, Verner thought he had found exactly what he needed.

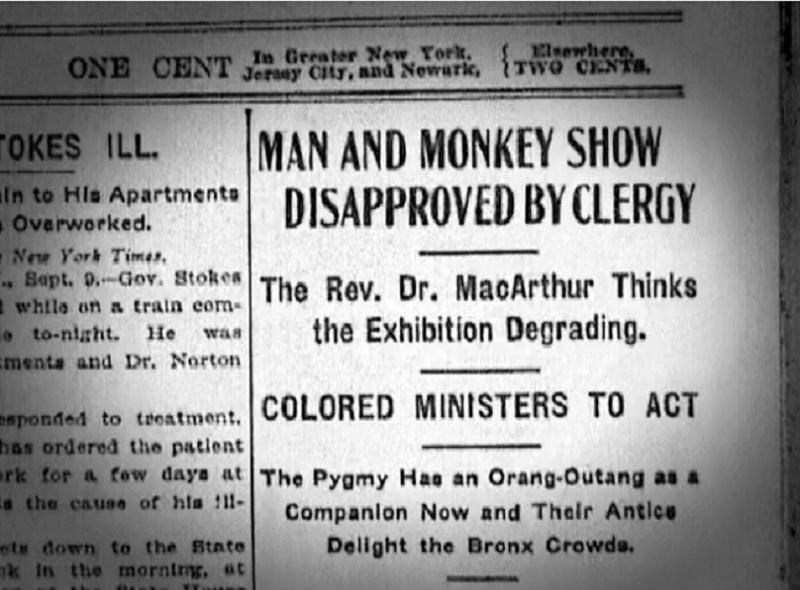

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Verner bought Benga for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth, and hauled him to the United States.

Benga and his fellow Africans were the hit of the World’s Fair, and afterward remained with Verner (who owned him, after all), and even traveled back to Africa for a short time. When he returned to the United States in 1906, Verner loaned Benga to the Museum of Natural History for a time. When the museum failed to pay Verner the salary he requested though, he decided to loan his African pygmy to the Bronx Zoo.

They were looking to expand their monkey house, you see.

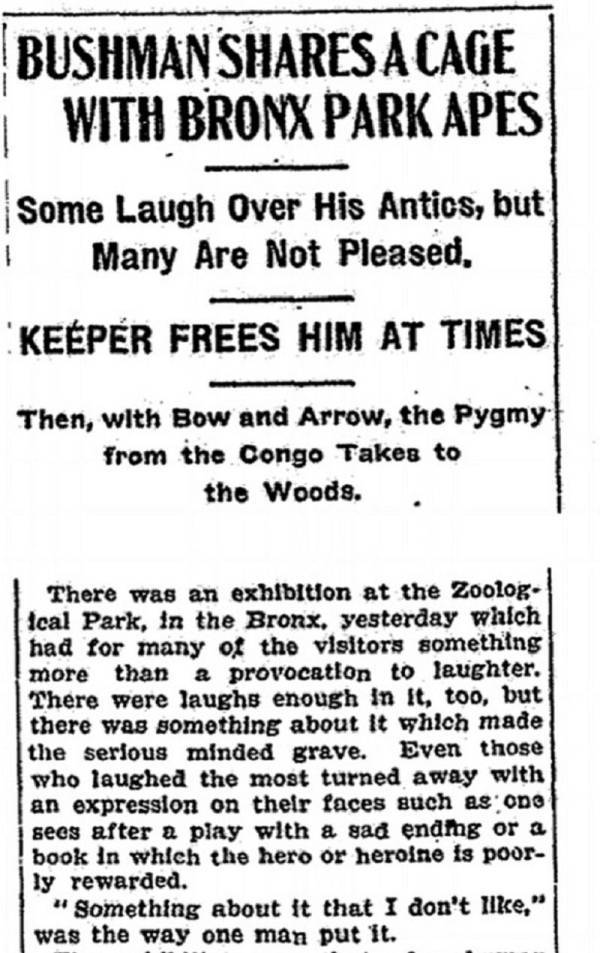

Photo Credit: Blogspot

Yeah. The Bronx Zoo kept a human being in the exhibit with their monkeys, his hammock slung between trees. He was displayed as part of the New York Anthropological Society’s exhibit on human evolution.

Luckily, not everyone at the time was a horrible excuse for a human being, and there was outcry from the clergy (and some laypeople) demanding Benga’s release. He was eventually freed, and minister James Gordon subsequently took custody of him.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Though Benga seemed to thrive for a while, even holding a job at a tobacco factory, he longed to return to Africa. Those plans were thwarted by the outbreak of World War I. This, combined with the German occupation of Belgium, meant no one was allowed in or out of the Congo.

On March 20, 1916, Ota Benga’s sad story ended with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the heart.

Though Benga reportedly made the best of his sad situation, it was clear that he was never happy being forced out of the home he was born into, and the thought of never being able to return to the land of his birth was enough to push him over the edge of despair.