Mmm, don’t you just love to hear the word “secretion” along with “flavoring?” No?

Well, here’s your fair warning – if you’re someone who likes to blissfully enjoy their food without knowing exactly what’s in it or where it came from, you should stop reading now.

If you’re the morbidly curious type, you’re my people. Please, read on.

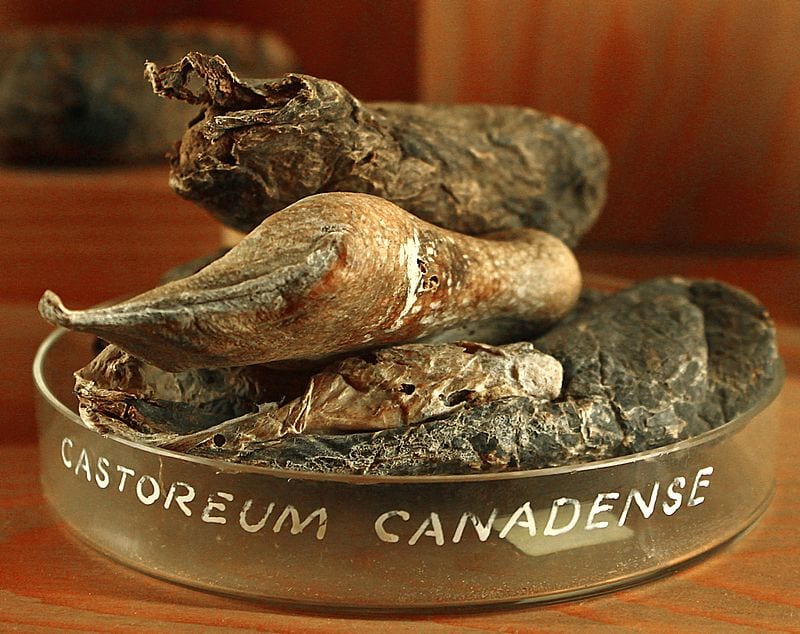

The substance in question is called castoreum, and is secreted from the anal glands of both male and female Alaskan, Canadian, and Siberian beavers.

The animals use the substance to mark their territory, and also to waterproof their fur.

Image Credit: H. Zell

Scientists can learn about the beaver’s health, based on the vanilla, raspberry, and floral hints in the castoreum. It ranges in color from yellow and milky to grey and sticky.

Humans have more recently used the fluid to make perfumes, and it can be extracted from a dead or living animal. Historically, it was used as a wide range of medicines – ancient Roman women believed it induced an abortion, and through the Middle ages it was thought to reduce fevers and treat headaches.

Only the latter has merit, according to modern medicine; the gland contains salicylic acid, which is the main ingredient in aspirin.

When the Europeans colonized America, beaver hunting came back into fashion and the castoreum was again bought and sold for medicinal reasons. It was recommended to help ease earaches, toothaches, colic, gout, to help a person sleep, and to promote general mental health.

Image Credit: Steve

In the 19th century, we see it also beginning to find its way into perfumes as a fixative – the ingredient that makes it last longer on the skin.

In the early 20th century, castoreum was first used as a food additive. The FDA considers it a “natural” flavor, meaning it derives from a natural source, and can be used to enhance or add fruity strawberry or raspberry notes. It can also be used as a substitute for vanilla.

Flavor chemist Gary Reineccius told NPR that the relative scarcity of the beaver is also an issue – the American beaver was nearly hunted to extinction in the 19th century.

“It’s not like you can grow fields of beavers to harvest.

There aren’t very many of them. So it ends up being a very expensive product – and not very popular with food companies.”

Once common, it’s now rarely used. Milking a live beaver is gross and arduous, and since we no longer hunt them for their pelts, nabbing one and squeezing it’s glands is a daunting process.

We consume around 300 pounds a year, compared with 2.6 million pounds of vanilla.

Image Credit: Moxfyre

Like men do with most things, we almost wiped out the North American beaver by the beginning of the 20th century.

See, it wasn’t as bad as you thought!

Sure, we used to consume goo milked from a beaver’s booty, but not anymore.

At least, not much.