In 2020, we see it every day—when a scientific explanation, based on years of research by skilled people, is offered as a reason for something, someone, somewhere chimes in that they know that explanation is untrue—their common sense tells them so.

How do you argue that point with someone who feels so strongly in their convictions, even though you know they’re wrong? You can start by using a chess analogy, courtesy of a Facebook user named Tom Denton.

Photo Credit: Facebook

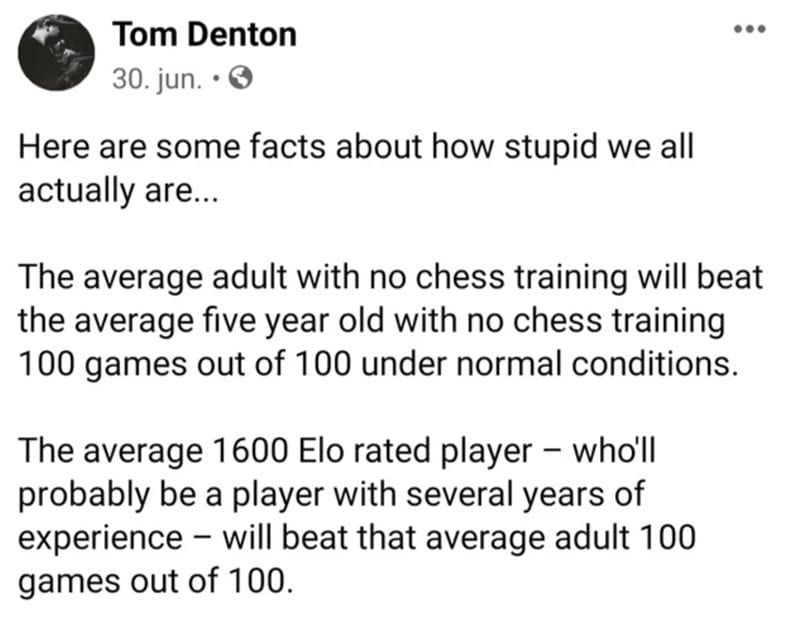

He points out what the chances are an average adult beating a child at chess and continues this train of thought by further noting how a high-level chess player would fare against an average adult.

Photo Credit: Facebook

He further continues by comparing that highly-ranked player to a Grandmaster.

While a highly-ranked player may come up with a move or two that might make the Grandmaster think, he’ll always beat that player.

Photo Credit: Facebook

To a Grandmaster, the child and the average adult are on the same level.

Photo Credit: Facebook

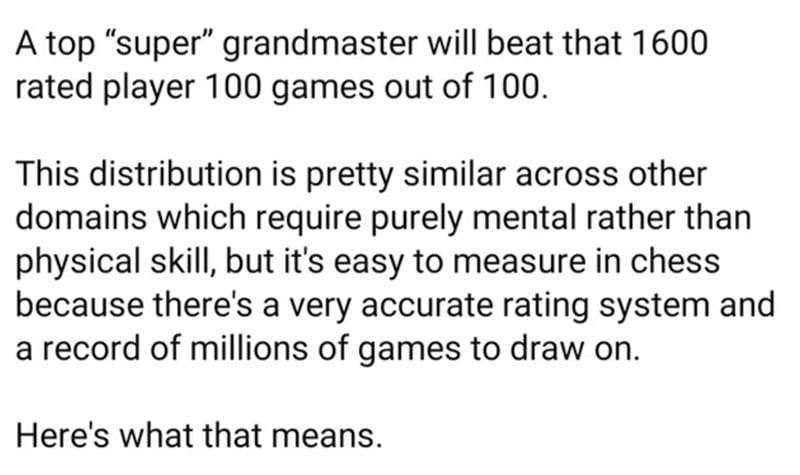

Now, take anyone who is top in their field—this expert is so far beyond the amateur, that he or she can’t comprehend the expert’s thought processes.

Photo Credit: Facebook

Therefore, common sense, based on no experience or research, is virtually worthless.

Photo Credit: Facebook

And the people who believe this is way, are not only wrong, they don’t even know why they’re wrong.

Photo Credit: Facebook

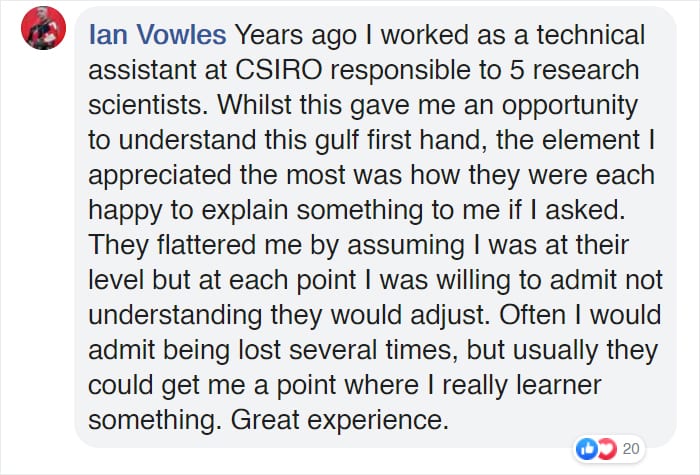

A lot of people REALLY agree with the post. Because they’ve run into this again…

Photo Credit: Facebook

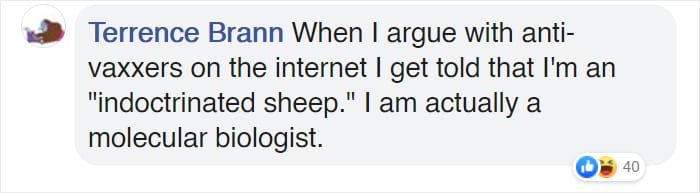

And again…

Photo Credit: Facebook

And again…

Photo Credit: Facebook

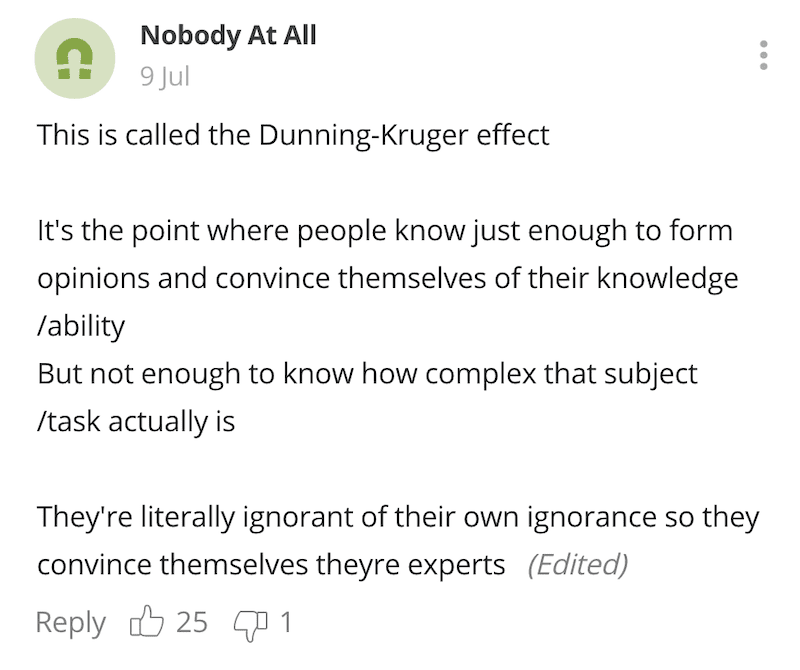

One reader called this an example of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Photo Credit: Facebook

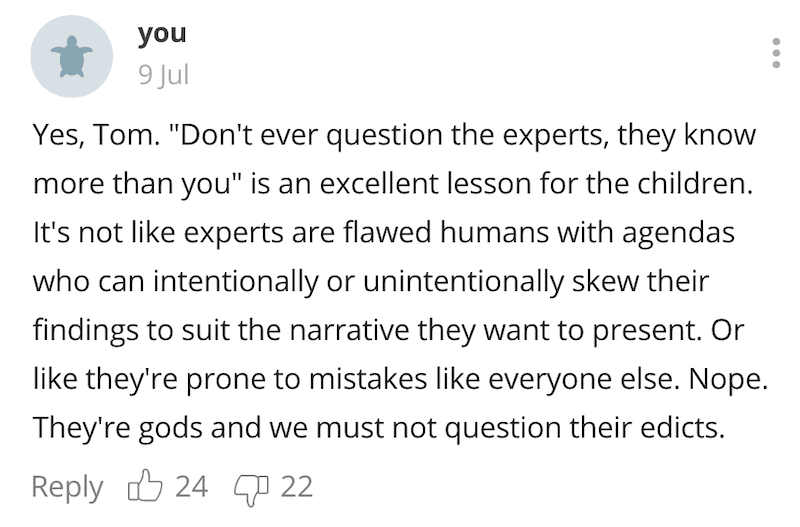

Others didn’t think the analogy worked as well as Tom thought it did, as experts are human too and can sometimes make mistakes.

Photo Credit: Facebook

Do you think that chess is a good analogy for what Tom was trying to convey?

Let us know in the comments below!