The Okjökull glacier was dead, declared Oddur Sigurðsson, a geologist in the Icelandic Meteorological Office back in 2014.

By then, the glacier had mostly disappeared.

Fast forward five years and Sigurðsson and other scientists are hiking to the old summit to place a plaque commemorating it upon the volcano it once dominated. It is officially the first glacier lost to climate change.

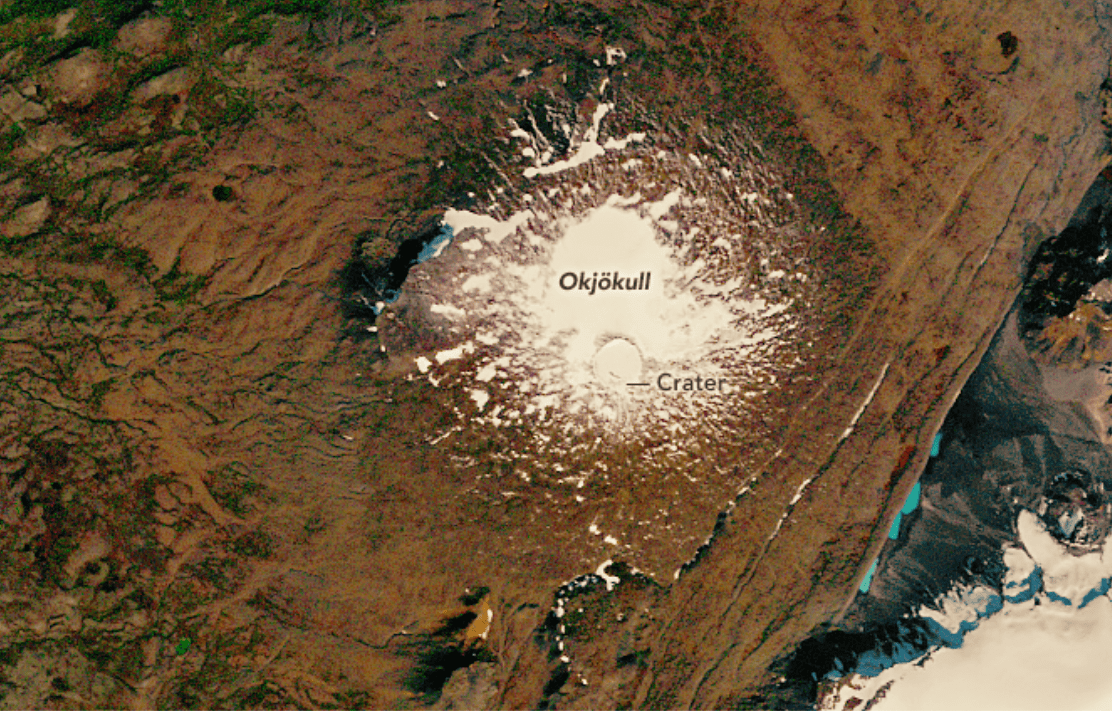

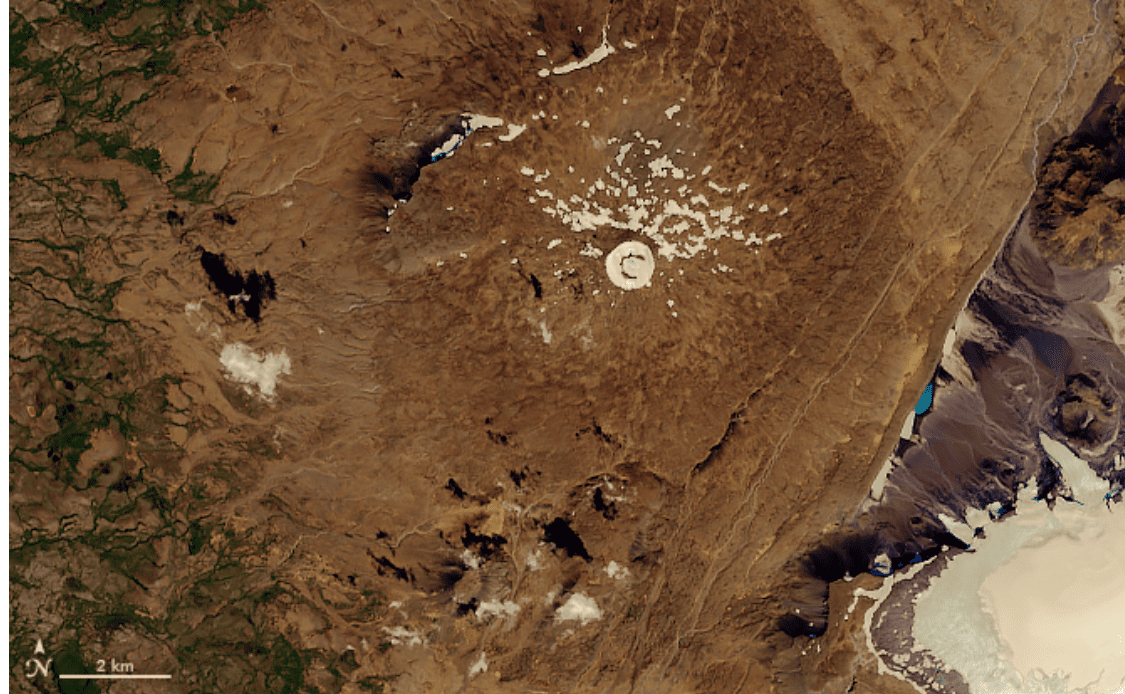

These dramatic satellite images show the tragic change of the glacier between 1986 and 2019.

The Okjökull glacier is only one of Iceland’s receding glaciers, many of which are also changing at dramatic rates. According to Sigurðsson, glacier conditions all around the world are on the decline due to the impending climate crisis.

He has been documenting the vanishing of approximately 56 out of the 300ish smaller glaciers in the northern part of Iceland.

Here is the image of the Okjökull glacier in September, 1986.

Photo Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Here is the image of the glacier taken August, 2019.

Photo Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Every continent, except for Australia which does not have glaciers, is experiencing the loss of glaciers, some slow, others much quicker.

Alex Gardner, a NASA glaciologist, told Mashable, “We’re not trying to figure out whether the glaciers will melt in the future. We’re just trying to find out how much and how fast.”

Since 2001, 18 of the 19 warmest years on record have occurred. The warm temperatures have thinned the rivers of ice that create the glaciers.

Photo Credit: Vojife

Sigurðsson calculated that in 1890 the Okjökull glacier occupied 16 square kilometers, or 6 square mile. By 1945, it was dwindling, and it eventually died in 2014. Now, only small amounts of snow and ice exist along the slope.

Assuming warming trends continue along with unchanged rates of carbon emissions – which seems to be our trajectory unless something dramatic happens in the global political landscape – Iceland will see a decline in its glaciers of 40 percent by the end of the century.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, all of Iceland’s ice masses could disappear by 2200, if not sooner.

In the meantime, Sigurðsson is taking on the sad task of tracking all the living glaciers, especially those in retreat.