In the 1880s, a man named James Edwin Wide worked for the railroad, where his main job was to listen for the whistle of approaching trains and change the track based on the specific sequence, which was a signal for where they were headed.

One day, James was visiting a South African market when he stumbled upon a chacma baboon that would change his life – the primate was driving an oxcart, and as a man with two peg legs, James thought perhaps he could put the enterprising baboon to work.

He bought him, named him Jack, and took him home. For awhile, Jack was content (I assume) to push Wide back and forth to work in a trolley and help out around the house sweeping floors and taking out the trash. Then, one day when the two were hanging out at the railway station, something remarkable happened.

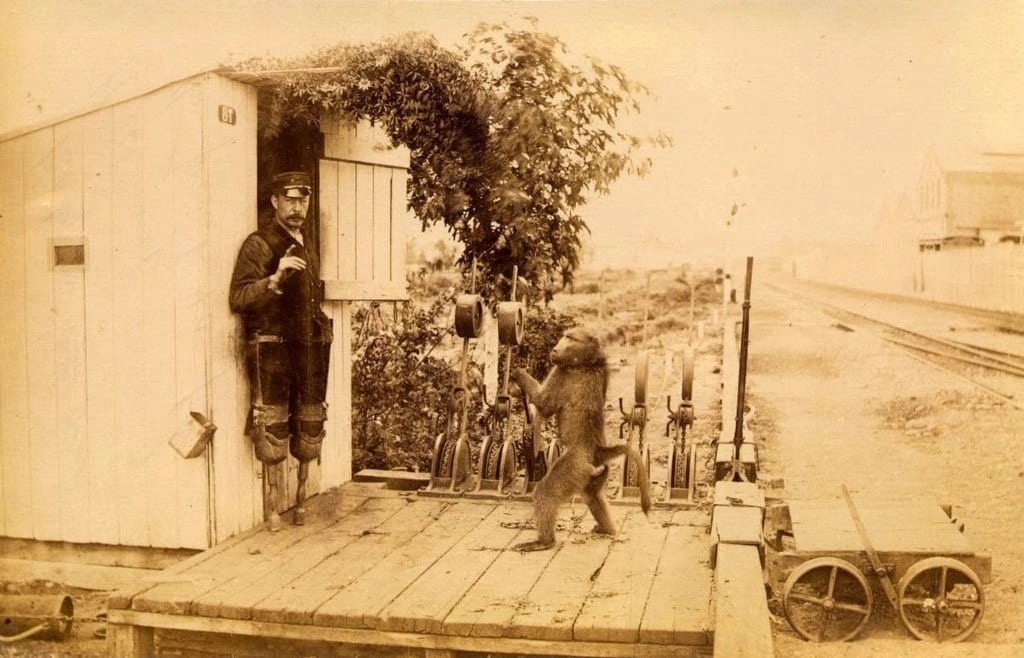

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

He had been watching Wide listen for the specific whistles and then pull levers for so long, he started to do it by himself.

Presumably, Wide oversaw Jack at the beginning, just to make sure he was really getting it right, but after awhile the human employee sat back and put his pegs up, letting the baboon do his job. According to The Railway Signal, Wide had “trained the baboon to such perfection that he was able to sit in his cabin stuffing birds, etc, while the animal, which was chained up outside, pulled all the levers and points.”

Now, I’m not sure how ethical this was or whether the PETA of the day would have had a fit (not to mention OSHA!), but aside from the chain, it sounds like the baboon was fine having a job. He was presumably well-fed and cared for, and who’s to say where he would have ended up had Wide not stumbled across him that one fateful day.

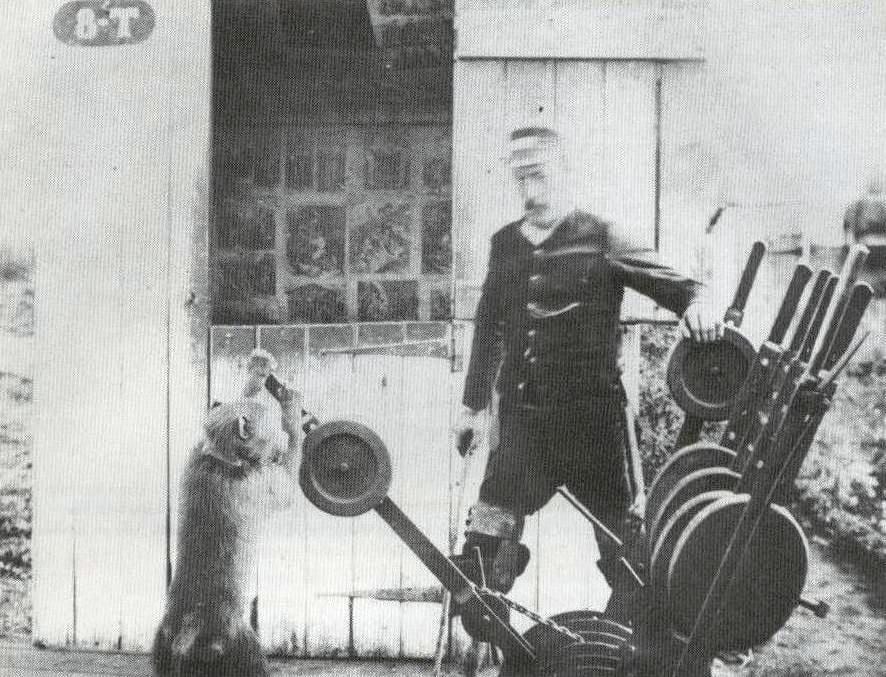

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Things came to a head when a train passenger became somewhat alarmed at the sight of a baboon pulling the levers that controlled their train and rang the authorities, but if you’re thinking that was the end of Wide’s sweet arrangement, you’re dead wrong.

The railway managers merely observed and tested Jack’s abilities, coming away astounded. Railway superintendent George B. Howe visited the animal around 1890 and left convinced no human could do the job better.

“Jack knows the signal whistle as well as I do, also every one of the levers. It was very touching to see his fondness for his master. As I drew near they were both sitting on the trolley. The baboon’s arms ’round his master’s neck, the other stroking Wide’s face.”

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Jack earned an official employment number and a wage of 20 cents per day (plus a half a bottle of beer a week, though I question the intelligence of wanting a drunk baboon on your hands). He worked for the railroad for nine years before he passed away of tuberculosis, and in all those years he never made a single mistake.

Jack’s passing reportedly left “the lonely signalman brokenhearted,” according to the Cape Mercury. And for good reason – he’d lost a pet and also had to actually do the job he was getting paid for every day. Must have been a real blow.