Although we’ve had our eyes on the Mars prize for some time, a different team of researchers are actually working on getting to Venus.

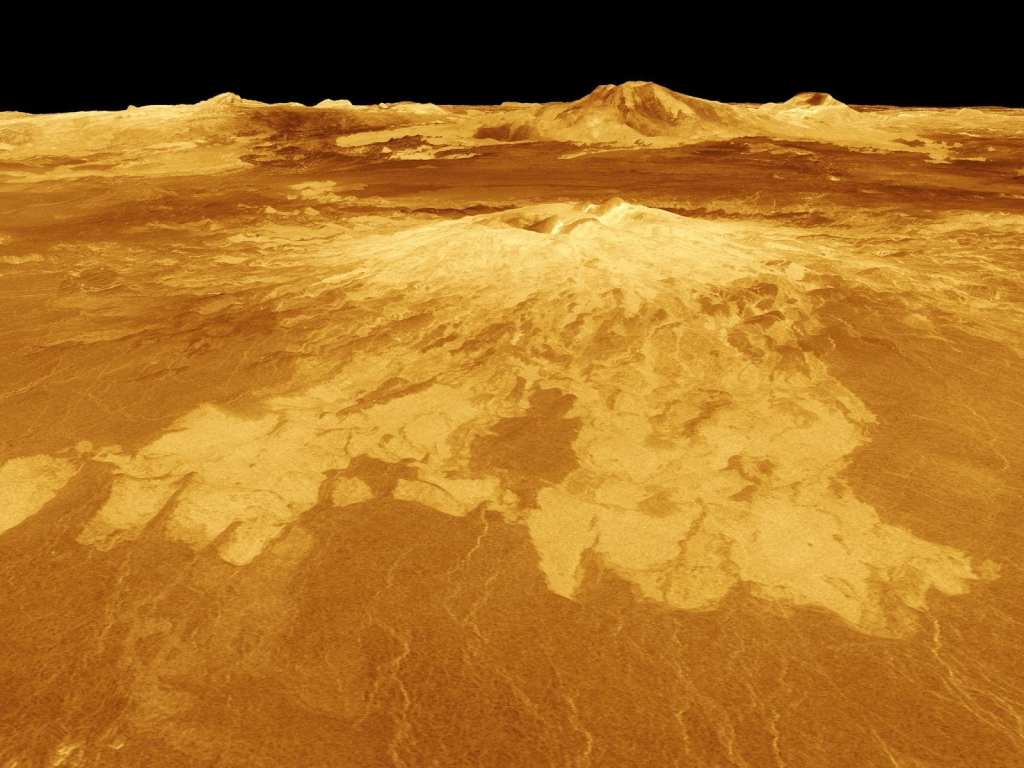

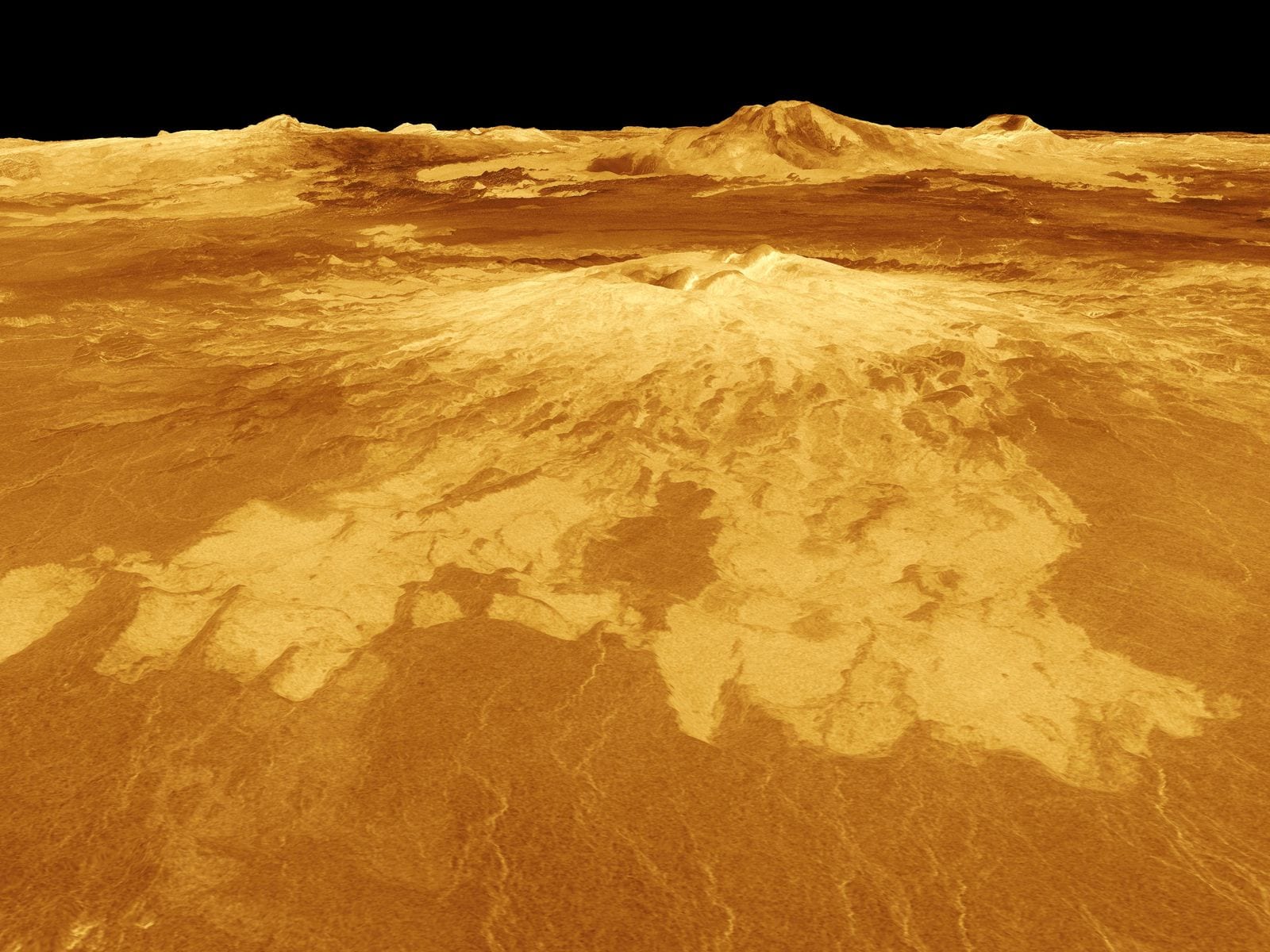

Venus gets closer to Earth in its orbit than any other planet, yet we have precious little information about the surface – except that it’s close to a living hell.

In 1966, a Soviet space probe crash-landed on the surface, where it lasted a few hours before being destroyed. Now NASA’s Long-Lived In-situ Solar System Explorer, or LLISSE, is looking to last a full 60 days in the reactive atmosphere, crushing pressure and blasting heat found on Venus’ surface. In fact, each probe has to be specially designed to withstand the high temperatures and pressure.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Called Earth’s evil twin, Venus is roughly the same size and mass of our home planet. Scientists say it was once water-rich, potentially with the elements necessary for life. But it has since turned into a hell planet with scorching, lead-melting temperatures, pressure comparable to what’s found at the bottom of our deepest oceans and winds whipping like tornados. During the day, sulphuric acid blocks the sun’s rays. The nights each last one hundred Earth-days.

One theory about what happened to make Venus so inhospitable is that, over time, the once huge, shallow ocean evaporated, releasing the super-light hydrogen atoms into space. As hydrogen disappeared, all the carbon-dioxide left in the atmosphere created an out-of-control greenhouse effect. Basically, turbo-charged climate change run utterly amok.

But we really don’t know.

And we can’t know, until we put some equipment on the surface.

Small as a ten-inch cube, LLISSE will piggyback on other space-going craft and then get dropped onto Venus. The unit is made of super hard silicon carbide – also used in sandpaper and lab-made diamonds – to protect it against sulphuric crystals. Like a missile, it will be powered by a heat-activated thermal battery for its 60-day life.

Photo Credit: NASA

NASA engineers need the unit powered for that long to see the change from day to night on Venus. Each Venus day lasts almost four Earth-months. If the unit can get placed late in the day, and if it can stay powered long enough, we’ll be get critical data on the transition for the first time.

Eventually, LLISSE will be used as part of a joint Venus project with the Russian space agency, but, as of right now, it looks as if nothing is getting to the next planet over before 2026. Frankly, it’s not even sure if LLISSE will ever get a trip into space at that point.

But the technology is already here, and Venus isn’t going anywhere.

A visit next door is just a matter of a few more Venus days.