In 1851, the Oatman family was traveling throughout Arizona and Southern California looking for a place to settle after breaking way from the Church of Latter-day Saints. The family had embraced the philosophies of Mormon rebel James C. Brewster, and had heard that California was the place to find other followers like themselves.

The Oatman family consisted of Royce and Mary Oatman and their 7 children, aged 1-17. They were traveling with a larger group of about 90 settlers that split, half heading to Sante Fe, and the Oatman-led group toward Tucson. As the latter approached Maricopa Wells in Arizona, the majority decided to stay after hearing horror stories about both the barren, dangerous trail, and hostile Native Americans in the area.

The Oatmans, though, decided to press on for Tucson. It would be a decision that would alter all of their lives forever.

They ran into trouble 90 miles east of Yuma, on the banks of the Gila River. A tribe of Native Americans, the Yavapais, waylaid the family asking for tobacco and food, and though the details aren’t known, the encounter turned hostile. The Oatman parents and the younger children were murdered, but when Lorenzo, 15, woke up after being beaten unconscious, he found that two of the bodies were missing – those of 14-year-old Olive and 7-year-old Mary Ann. Lorenzo managed to walk back to the nearest settlement, where his wounds were treated before he returned to the scene of the massacre with some of others.

They surveyed the scene and searched, but still, Olive and Mary Ann were nowhere to be found.

Photo Credit: Wild West History

The Yavapais had taken the sisters, along with prizes from the wagon train, to their own settlement. The tribe treated them as slaves, and forced Olive and Mary Ann to forage for food. Olive later said they were sure the whole time that they would be killed at any moment.

Things began to look up for the girls when the Yavapais traded them to a tribe of Mohave for some horses, blankets, and other supplies. They trekked through the desert yet again, unsure of what awaited them ahead, but with little choice but to go along.

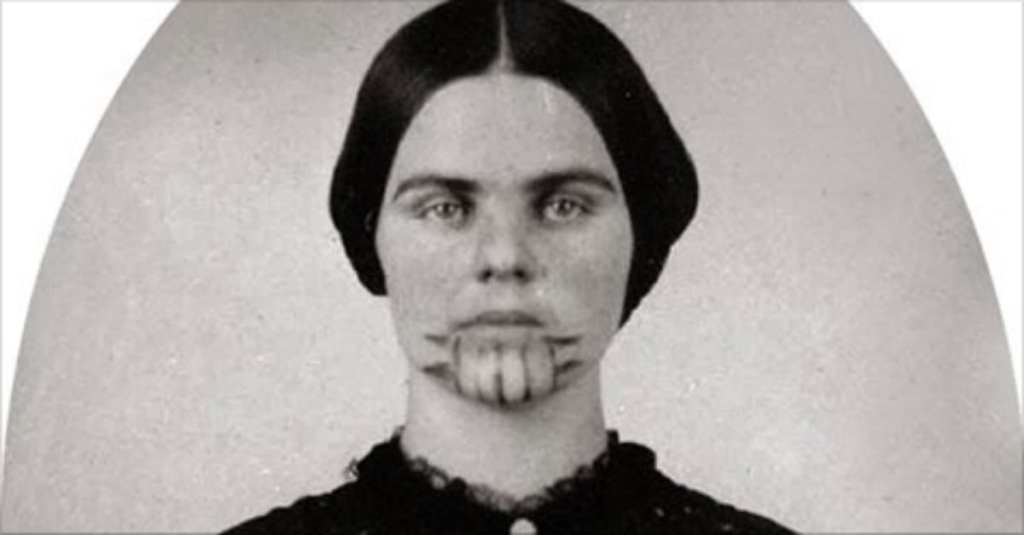

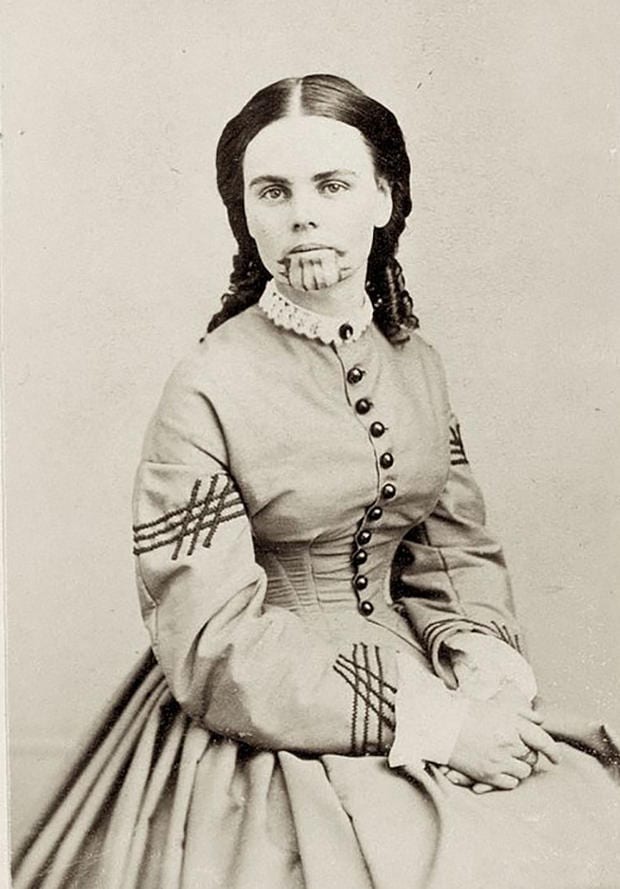

They were pleasantly surprised when life among the Mohave proved much more tenable. The tribal leader took the two of them in and treated them like family and full members of the community. To make sure that others saw them as such, both girls had their chins and upper arms tattooed with thick, blue cactus ink. The purpose of the tattoos was to mark everyone as Mohave, and ensure that they would be recognized by their ancestors in the afterlife – interesting, considering the girls were not genetically Mohave.

The scenery in the idyllic valley was an improvement as well, and now that the girls were no longer treated as slaves, they relaxed into their lives (according to this 1856 newspaper account). They were given land and seeds to grow their own crops and were beloved by both the tribal leader’s wife and daughter. By all accounts the two were happy in their situation – so much so that when a group of white railroad surveyors spent a week among the Mohave during the Whipple Expedition, neither of the girls snuck away to inform them they’d been abducted.

Photo Credit: Margot Mifflin

Around 3 years after their original capture, Mary Ann starved to death during a drought and subsequent crop shortage. Olive said later that she only survived because her adoptive mother fed her in secret while many of the others in the tribe went hungry.

In 1855, Francisco, a member of a neighboring tribe of Quechan people, relayed a message from the federal government officials stationed at nearby Fort Yuma – the authorities there had received word that a white woman was living among the Mohave, and they demanded an explanation for her presence and/or a statement as to why she wished to remain.

At first, the tribe ignored the request. They reconsidered due to their fear of reprisal from the federal government, and even included Olive in the negotiations as far as how to handle the situation.

“I found that they had told Francisco that I was not American, that I was from a race of people much like the Indians, living away from the setting sun. They had painted my face, and hands, and feet of a dun, dingy color that was unlike that of any race I ever saw. This they told me they did to deceive Francisco; and that I must not talk to him in American. They told me to talk to him in another language, and to tell him that I was not American. Then they waited to hear the result, expecting to hear my gibberish nonsense, and to witness the convincing effect upon Francisco. But I spoke to him in broken English, and told him the truth, and also what they had enjoined me to do. He started from his seat in a perfect rage, vowing that he would be imposed upon no longer.”

It’s hard to say what changed Olive’s mind about remaining with the Mohave – her sister’s death, perhaps, or maybe something else had been altered that she chose not to include in her account of the happenings. Whatever the reason, the jig was clearly up, and Olive Oatman was returned to American society shortly thereafter.

Five years after her family’s murder and her subsequent abduction, Olive wept into her hands as the fort’s commander welcomed her. They asked that she wash the paint from her face, the dye from her hair, and dress in appropriate Western clothing before entering the fort, where she was later reunited with her brother Lorenzo. Olive barely remembered how to speak English, and she relayed several incorrect details about her capture, starting with the fact that she told them she was 11, and not 14, when her family was killed.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

There were other inconsistencies in how she spoke of her time away, as well. She denied that she was ever treated unfairly or engaged in sexual contact with either tribe, but she confessed to a friend (according to the friend) that she had married a Mohave man and had two sons with him – and that her depression upon returning to society was actually grief at having left them behind. Olive always denied this when asked about it in public. She said that the tattoos on her face were put there to mark her in case she tried to escape, but neglected to mention that all Mohave women bore the same markings.

Even though Olive herself thought fondly of her time with the Mohave and even, some say, longed to return to her live there, she helped promote a book published about her captivity that painted Native Americans in a savage, unflattering light.

Perhaps we can’t blame her, since the pressure would have been great to deny that she had been marred in any serious way after she returned to “civilized” society. She was already marked by tattoos – if her virtue had also been seriously questioned, all of her prospects would have been destroyed.

The pressure would have been great in many ways, since both her beauty and her face tattoos, along with her story, made her an instant celebrity. Despite how vehemently she denied having an Indian lover or husband, the rumor stuck – largely due to a Los Angeles Star article that reported (a month before Olive’s return) that both Oatman girls had been found alive and married to Mohave chiefs.

Olive did marry, and the couple settled down and adopted a baby girl. Olive barely left the house and repeatedly struggled with both depression and headaches, and always covered her tattoos with oil or makeup before leaving the house. She never seemed to get over the trauma of her early life and died of a heart attack in 1903.

In 1857, a Methodist minister wrote the original account of Olive’s story, Life Among the Indians (later re-titled Captivity of the Oatman Girls). There’s a more recent 2009 biography as well, called The Blue Tattoo, which is generally thought to be more faithful.

Me? I think there’s a whole lot about Olive’s story that doesn’t add up. Why didn’t she know how old she was when she was captured? Did she really want to leave, or was she forced for some reason (perhaps to save her children)? I personally think that Mary Ann, her sister, never died. She probably chose to stay with her husband the Mohave chief while Olive fell on her sword, so to speak, and returned to society.

The reason I think that is because no one would eat in private while she watched her baby sister starve to death. I don’t care who you are.

Maybe it’s that I’m a writer and I have an overactive imagination. Could be.

Or I could be right.

What do you think?