Trending Now

A nice job, a beautiful family, and a nice little house with a white picket fence – this is the stuff the American Dream is made of.

Owning a little piece of land out in the suburbs, where the grass is green and the neighbors are friendly, where kids grow up playing baseball into the evening, where you can be the king/queen of your own little castle.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Home ownership is one of the most essential ways to build wealth, as homes generate equity and appreciate in value over time.

The money that generates, especially if you sell your house for a decent return on the initial investment, can help your kids go to college or buy their own first home, and so on and so forth.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

As idyllic as that picture of the suburbs might seem, there’s one very glaring flaw in it: the housing market in America is marked by a long and shameful history of racial bias. For decades, federal and state-sanctioned legislation has explicitly denied minorities – African Americans in particular – access to the aforementioned American Dream.

Where it Began

While racial segregation has long been a part of American life, there appeared to be a sliver of hope in the immediate aftermath of WWII, as the federal government created sweeping reforms nationwide to provide Americans with more opportunity. Among these were the G.I. Bill, aimed at providing returning veterans with a host of benefits including educational opportunities and favorable financing.

The relatively recently-formed Federal Housing Administration (henceforth referred to as the FHA) was also actively helping veterans and civilians alike with obtaining financing by underwriting and providing insurance to banks on housing loans.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Unfortunately, these benefits went disproportionately to white families.

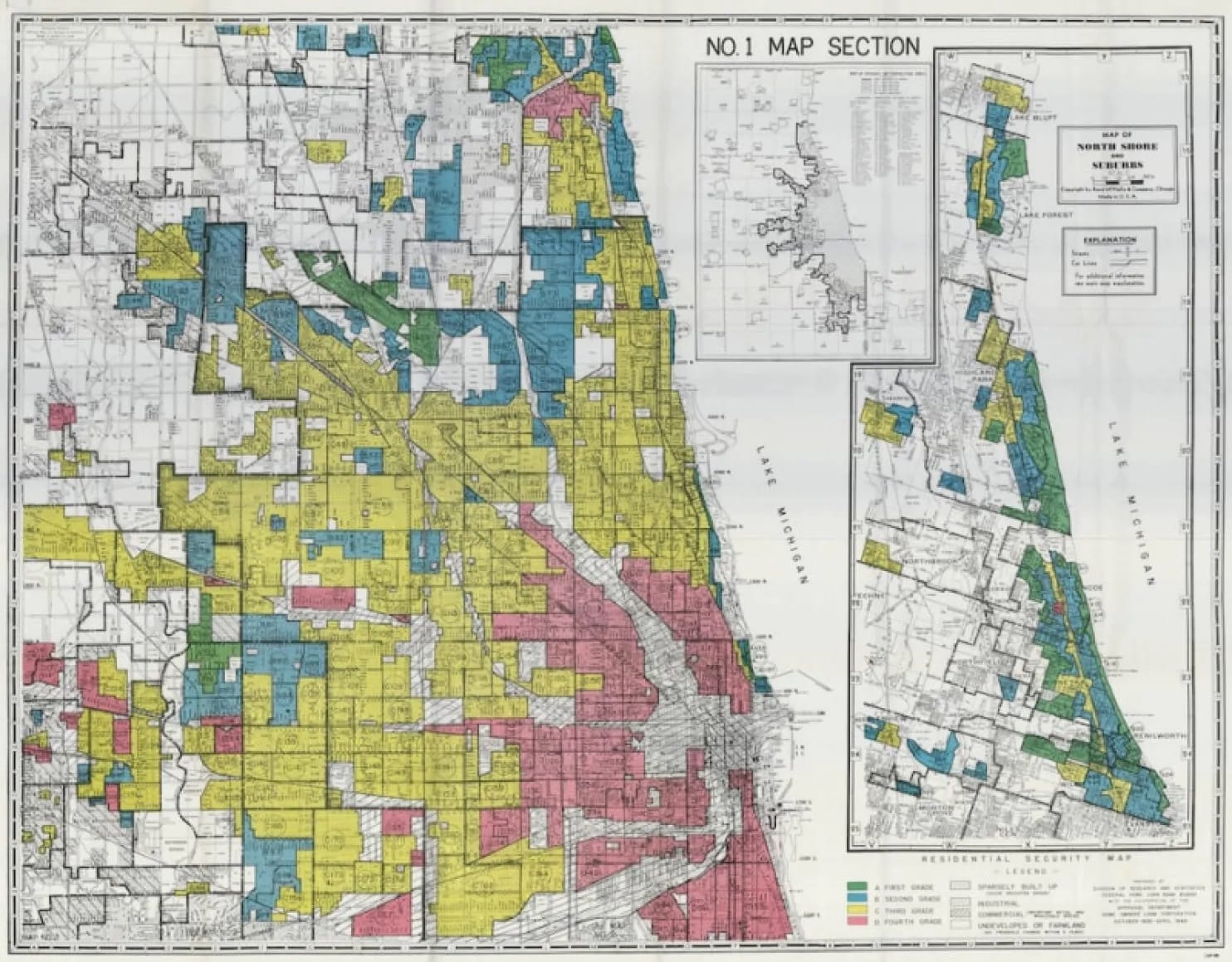

A disappointing number of returning African American veterans, thinking things would finally be different now that they’d fought for the country, were denied their GI benefits. The FHA also gave banks a system by which to determine which neighborhoods they could safely lend to, which places to charge more, and which places to deny outright. This system rated neighborhoods on a number of factors, paying special attention to the type of population.

Guess which neighborhoods (and subsequently, all of their residents) were at the bottom of the rankings?

Redlining

Yep, if you had the misfortune of being black in a predominantly black neighborhood, you may as well just forget about your chances to buy a home.

The ratings system used by the FHA marked off mixed/predominantly minority neighborhoods as “high risk” for safe lending, effectively eliminating any chance these residents might have had at getting out of there. These neighborhoods were marked in red, giving rise to the term “redlining.”

Living in or even near a redlined area could have disastrous long-term consequences for your upward mobility.

Photo Credit: Economic Policy Institute

Let’s be clear about one thing: this was not a result of African Americans not having enough money to buy homes.

Though it’s true that African Americans as a whole had less money than their white counterparts at the time, there were still plenty of them (particularly returning veterans) who could afford a piece of suburban bliss – provided they got the same financing benefits as everyone else.

Dream Denied

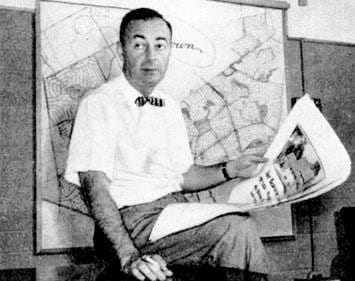

Worse still, even if they could get the money, many suburban housing developments refused to accept their offers. The famous Levittown developments, for instance, had languaging in their lease agreements that explicitly forbade the sale of property, or even occupancy, to anyone who wasn’t Caucasian (they did allow people to have non-Caucasian servants). William J. Levitt, the mastermind behind Levittown, defended the policy by saying:

The Negroes in America are trying to do in 400 years what the Jews in the world have not wholly accomplished in 600 years.

As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. This is their attitude, not ours.

As a company, our position is simply this: We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem, but we cannot combine the two.

True as that may have been, Mr. Levitt was hardly an innocent bystander.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When some Levittown residents pushed for integration, the company branded them Communist rabble-rousers and barred them from having meetings. They also evicted residents for inviting black children to their homes and continued to openly defy anti-bias laws once they were passed.

To be fair, however, black people weren’t the only targets. Despite being the grandson of a rabbi, Levitt also built housing on Long Island that excluded Jewish people.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Matters were only made worse by restrictive covenants formed by neighbors with the purpose of barring sale or occupancy of a local home to people of color. These covenants gave neighbors the power to evict the colored occupants of a home, and to also sue the homeowner who allowed the sale/rental to occur in the first place!

Locked Out

Along with redlining, real estate agents used another nefarious means of enforcing segregation – “block-busting.”

They would get a black family to move into a white neighborhood or hire black people to walk around the area with baby carriages and just generally feed into negative stereotypes. This would create a panic amongst white homeowners, who felt that black people would ruin the neighborhood.

Those homeowners, egged on by the real estate agent, would end up selling at a lower price out of fear, at which point the real estate agent scoops it up and sells it to other black families at a steep markup. It wasn’t uncommon for homes that once housed a single white family to be rented out to three or more black families, with a sharp increase in rent to boot.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

By the way, this idea that black people couldn’t maintain their property? It was spurred on by the observation that predominantly black neighborhoods were often in disrepair.

What nobody bothered to learn about though was the fact that this was due to intentionally limited municipal services (such as garbage collection) to black neighborhoods.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

As a result of this systemic inequality, minorities were largely locked out of being able to accumulate wealth the way their white counterparts did in the years following WWII (a condition which persists to this day). Where you live can strongly affect all kinds of effects on really important things like as jobs, education, and healthcare.

For a sizeable number of the African American population, poverty became a way of life that, in many cases, was quite literally inescapable.

A Flash of Hope

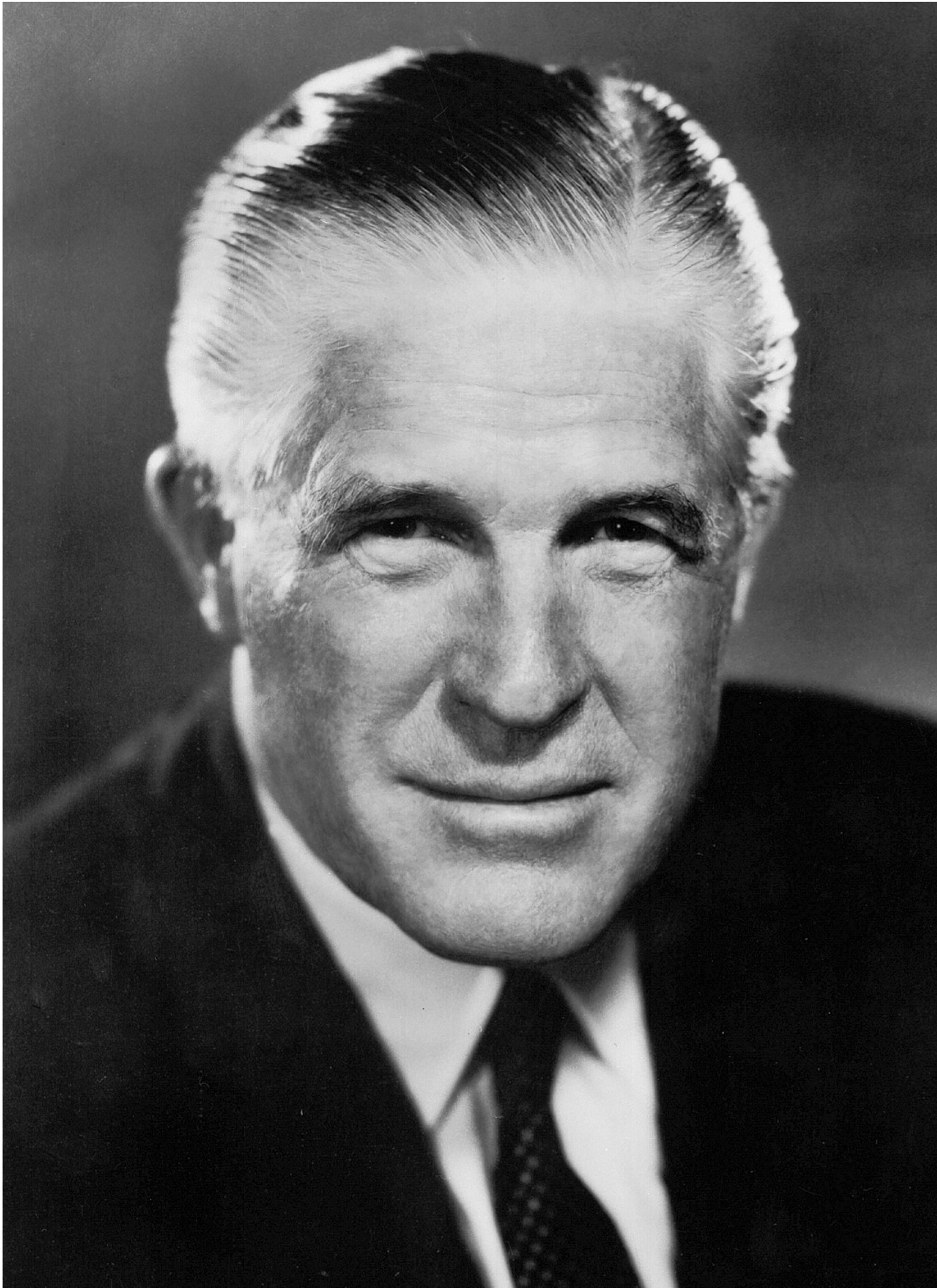

Surprisingly, some of the most ambitious legislation to date towards ending residential inequality came early on during the Nixon administration.

George W. Romney (Mitt Romney’s dad), then-newly-appointed secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), had some bold ideas about destroying the “high-income white noose” around black inner cities. He ordered HUD officials to reject applications for sewage, water, and highway projects from areas where local policies helped create segregated housing.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The initiative, dubbed “Open Communities,” wasn’t cleared with the White House and Nixon’s supporters in the South and in white suburbs up North quickly pressured the President to put a quick stop to it.

Romney felt that “equal opportunity for all Americans in education and housing is essential if we are going to keep our nation from being torn apart.”

Sadly, his position made him an outcast within the administration, and it wasn’t long before he was pushed out of his position.

Here and Now

Despite further legislation limiting housing segregation, today’s America is in some aspects more segregated than it’s ever been.

Real estate companies, developers, landlords, lenders, and housing authorities might have learned to stop talking about their racist ideas, but they haven’t stopped practicing them. Minority home buyers are still more likely to face steeper terms on loans than white counterparts with a similar socioeconomic background, realtors still outright refuse to show certain properties to non-white clients, and landlords are still more likely to rent to white tenants.

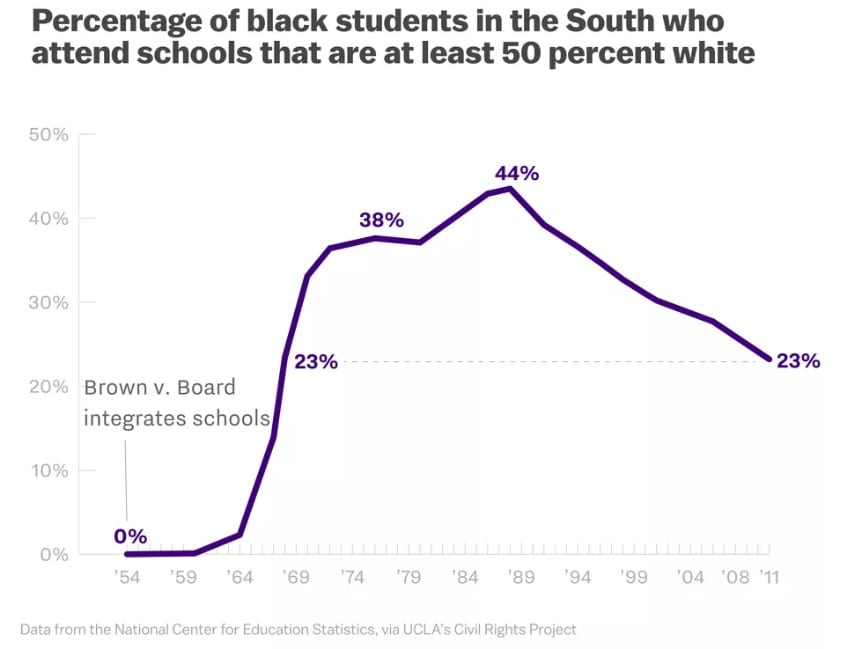

Thanks to creative zoning and gerrymandering of districts, black and white neighborhoods remain largely segregated and black and white children now attend schools that are sometimes even more segregated than they were before Brown v. Board of Education!

Photo Credit: Vox/UCLA Civil Rights Project

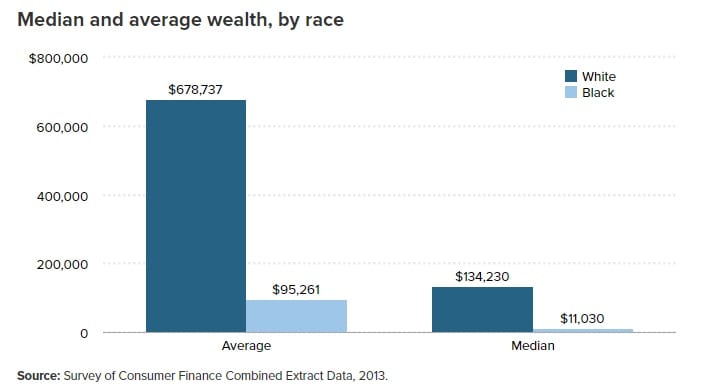

Furthermore, while some may argue that closing the income disparity gap over the years has helped, the numbers tell a different tale – especially when you consider wealth disparity instead of just income. Median black families now make about 60% of what the median white family makes (… yes, this is considered progress). However, the overall wealth of the median white family amounts to 10 times as much as the median black family – largely as a result of residential inequality.’

Photo Credit: Economic Policy Institute

Conversations like these are difficult to have because nobody wants to be made to feel like they haven’t earned the life they have. That first generation of post-WWII home buyers did what anyone would have done: they took whatever leg-up was available to them and like any good parents, they then passed on the benefits they received to the generations that came after. Some of them were in favor of inclusionary housing – but were either ostracized for it or simply didn’t fight that hard to change things.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Trying to blame or belittle the recipients of these benefits is just as counterproductive to solving the underlying issues as it is to imply that minorities are just too lazy to succeed. Still, it’s evident that we can’t have an honest discussion about wealth or inequality in America without simultaneously discussing race.

The conversations may be uncomfortable, but the hard work required to create genuine progress and lasting change rarely ever is.