If you’ve never heard of the prison-industrial complex, you aren’t the only one. The term comes from the more famous 50s-era jargon “military-industrial complex”, and it refers to how the growth of the United States’ prison population has deep roots in corporate profit-making. Since this isn’t as far out in the public eye as perhaps it should be, we thought we’d devote a little bit of metaphorical ink to exploring the ways people turn a profit off of imprisoning convicts and detainees – by contracting to contain and care for prisoners and utilizing their labor – and the roots of the practice.

Photo Credit: iStock

The origins of modern convict labor go all the way back to the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which finally banned slavery. The exact words of the amendment are:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

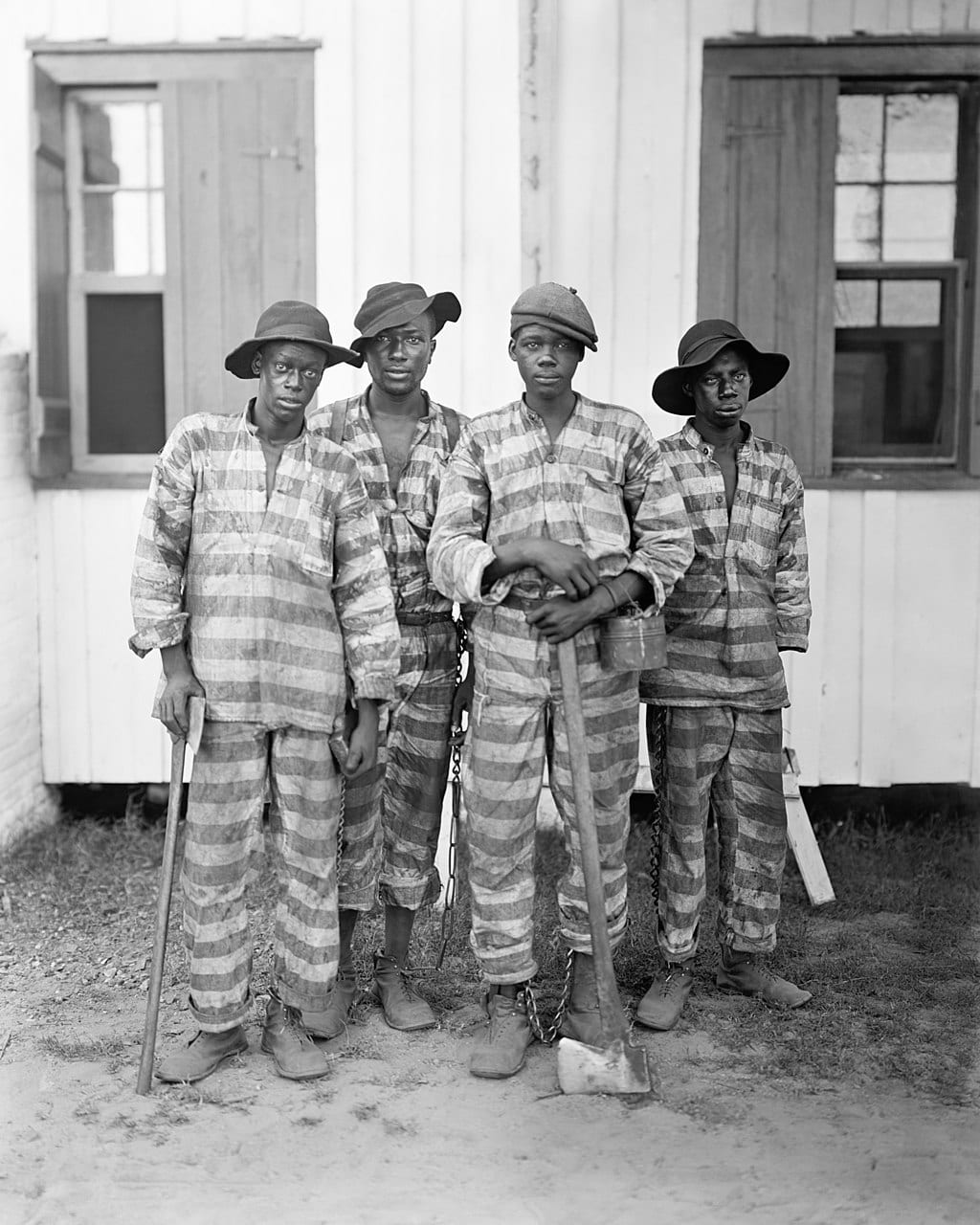

Right smack in the middle there is a big loophole – if you’ve been convicted of a crime, you can be forced into labor. In the aftermath of Reconstruction, this loophole was immediately put to use. Slave states passed laws that targeted recently-freed slaves, put them in jail (often without evidence of their supposed misdeeds), and leased their labor out to private companies and individuals. The practice was called ‘convict leasing’, and it allowed state governments to add huge sums to their coffers – in 1898, nearly 75% of Alabama’s state revenue came from leasing convict labor. Conditions for leased convicts were so horrifically bad that they were 10 times more likely to die than un-leased convicts.

Convicts leased to harvest timber circa 1915, in Florida. If you’ve ever heard of a ‘chain gang’, this is what that refers to.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Though you might think the brutal ways of the Jim-Crow-era convict leasing are of the past, in some ways, they’re not at all. Today, prisoners are still forced to work under pain of punishment (usually solitary confinement, aka ‘segregation’), sometimes in fields or in mines, and in many instances they’re paid pennies an hour. And starting with Nixon’s racist drug laws and continuing through Reagan’s mandatory minimums and Clinton’s 3-strike law, the prison population exploded, filling disproportionately with minorities – particularly African Americans.

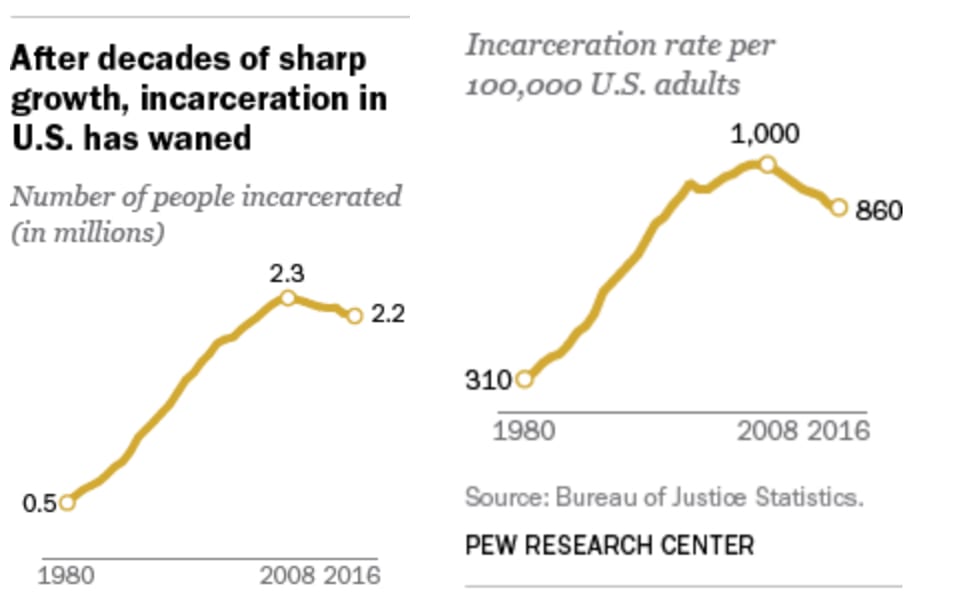

Though the U.S. prison population has started to decline in the past few years, it is still astronomically high.

This graph includes state and federal prisons, as well as locally run jails.

Photo Credit: PEW Research

America currently has the highest rate of imprisonment per capita in the world, leading El Salvador in second place. We have more prisoners in our population than any other country acknowledges, although the way that China counts its 1.6 million prisoners means that there could be as many as 650,000 uncounted, which would move it from #2 to #1.

With that background in mind, let’s talk about the cheddar.

Photo Credit: iStock

There are a number of ways that people make money off the backs of prisoners, but the primary methods are these: private companies can run services to public prisons (think phone companies charging prisoners to call out), private companies can use prisoner labor to make their products, or private companies can get contracts from the state or federal government to build and operate prisons.

All three of these methods are big business – privatized healthcare for prisoners, just one sector of privatized prison services, was estimated to be a $3 billion industry in 2016, and in 2015, privately-run prisons were worth a whopping $70 billion. Private prison companies and service providers are often financed or owned by Wall Street; hedge funds own huge stakes in private prison companies like The GEO Group and CoreCivic, which between them control and operate over 50% of the private prison contracts in the United States.

Photo Credit: Corecivic.com, Geogroup.com

But let’s back up for a second. How did corporations even enter the business of imprisonment?

Privately-operated prisons started popping up in the 80s with the rise of nonviolent drug sentencing. When prison populations started to skyrocket, overwhelming government-operated prisons, states struggled to raise the income they needed to build enough prisons to house their new prisoners – so they started signing long-term contracts with private companies to build and operate prisons. And voila, the modern for-profit prison industry was born.

To hammer home the point of just how impactful the war on drugs was on the skyrocketing prison population.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Privatization of services is supposed to save the government money while allowing the market to innovate solutions that can keep corporations making money as well. But in practice, there is no evidence that this actually happens. According to a 2016 report from the Hamilton Project, a liberal-leaning think tank, the evidence regarding whether private prisons save money over public prisons is unclear – what cost savings do appear come primarily from understaffing and paying prison guards less. A separate meta-analysis of the available data showed “that private prisons were no more cost-effective than public prisons.” And a 2016 report from the Office of the Inspector General said that private prisons are less safe for prisoners than government run prisons.

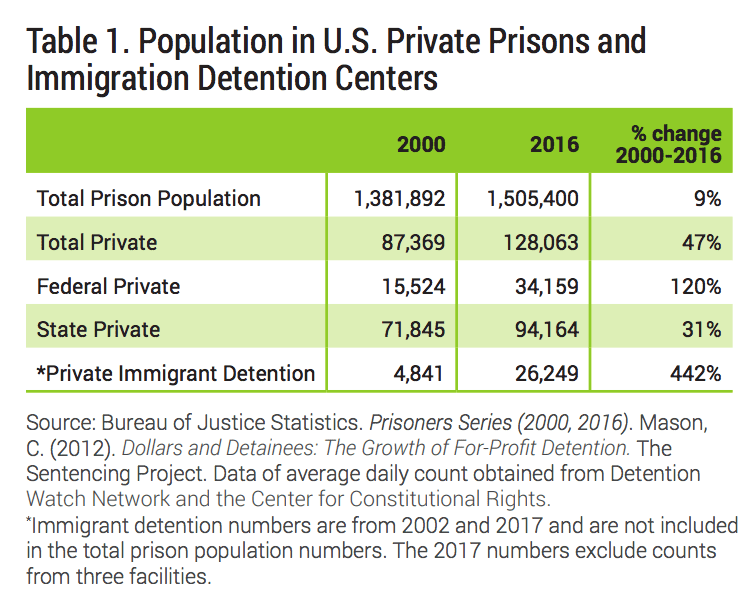

But regardless of whether they are actually better by any measure, over the past 20 years, privately-operated prisons have grown enormously.

This graph take into account *only* state and federal prison populations, leaving out locally operated jails

Photo Credit: The Sentencing Project

In 2013, a report released by In The Public Interest documented details of how private prison corporations were adding guaranteed occupancy clauses into the contracts states were signing. These clauses meant that states would guarantee to either fill beds, or pay the company the amount a filled bed would cost. In essence, either the state had to match a quota of prisoners, or, on the off chance crime came down, the state’s taxpayers had to foot the bill for the lost revenue. Either way, the prisons made money.

A few states signed these contracts, some guaranteeing occupancy as high as 90% or even 100%.

Other states have signed un-cancelable, multi-decade contracts with private companies to build and operate prisons, with a fixed amount of money (millions of dollars) paid out per year of contract – regardless of the actual cost of managing the prison. The incentive for companies to provide the cheapest, lowest quality services is obvious: any difference between the proscribed annual payment and the prison’s costs is all revenue. But again, taxpayers pay the same, regardless of how prisoners are treated.

Though there are arguably some potential benefits to private prisons, the gap between the hypothetical and the actual is pretty huge, and some private prisons and immigrant detention centers are pretty horrific on the inside. More than one large private prison corporation has been sued over inmate conditions – and that should raise alarm bells. Because when you’re making money off the powerless, what can they do to curb abuses?