If you grew up in the United States, there’s almost no chance you don’t know who the Peanuts gang are. Even if you’re too young to realize that they were born as comics, and even though there isn’t an updated version on Nickelodeon, the holiday specials have pretty much ensured that Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and the rest are forever lodged in American culture.

In 1968, though, the Peanuts gang were anything but nostalgic history. At the height of its popularity, Charles Schulz and the world he created were about to break barriers with the introduction of its first African American character, Franklin Armstrong.

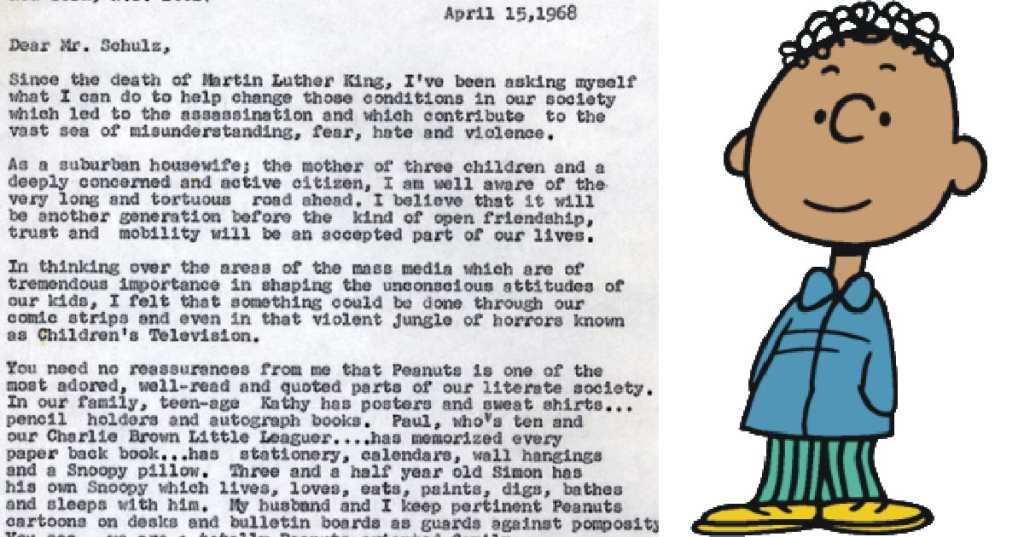

It was April of 1968 when Los Angeles-area schoolteacher Harriet Glickman, who thought media had a role in shaping the views and attitudes of children, wrote a letter to Schulz:

Image Credit: Charles M. Schulz Museum

“Since the death of Martin Luther King, I’ve been asking myself what I can do to help change those conditions in our society which led to the assassination and which contribute to the vast seas of misunderstanding, fear, hate, and violence. …the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters could happen with a minimum of impact. The gentleness of the kids … even Lucy, is a perfect setting. The baseball games, kite-flying … yes, even the Psychiatric Service cum Lemonade Stand would accommodate the idea smoothly.”

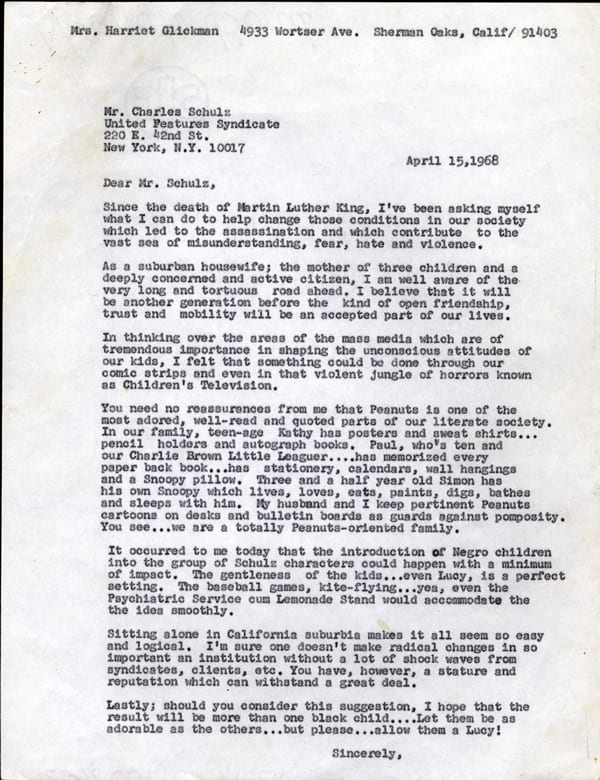

Schulz replied to the letter, telling Glickman what he would “like very much to be able to do this,” but confessed that he and other cartoonists were “afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends.”

Image Credit: Charles M. Schulz Museum

He told her he didn’t know what the solution was, and Glickman took that as a challenge to help him figure it out. She offered to pose the question to some of her Negro friends and get back to him, to which Schulz replied that he would be “very anxious to hear what your friends think of my reasons for not including a Negro character in the strip.”

They corresponded back and forth for some weeks, and the letters culminated in a strip, to be published on July 31, 1968, that Schulz told Glickman he thought would please her.

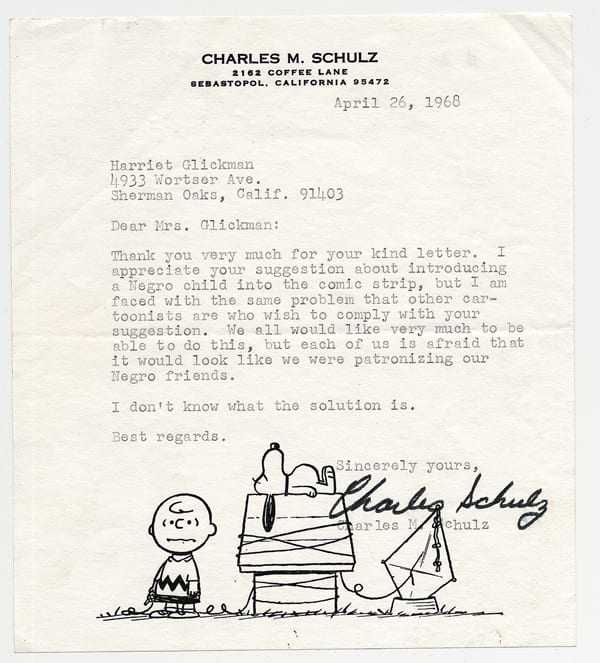

Franklin Armstrong entered the Peanuts strip that day, the first Black and first minority character to appear in any major, mainstream comic strip.

Image Credit: Fair Use

Later in his career, Schulz spoke about the particular strips featuring Franklin that received pushback from his editors.

“There was one strip where Charlie Brown and Franklin had been playing on the beach, and Franklin said, ‘Well, it’s been nice being with you, come on over to my house some time,’” Schulz recalled. “[My editors] didn’t like that. Another editor protested once when Franklin was sitting in the same row of school desks with Peppermint Patty, and said, ‘We have enough trouble here in the South without you showing the kids together in school.’ But I never paid any attention to those things, and I remember telling [United Features president] Larry [Rutman] at the time about Franklin—he wanted me to change it, and we talked about it for a long while on the phone, and I finally sighed and said, ‘Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?’ So that’s the way that ended.”

When Harriet Glickman passed in 2020, the director of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Karen Johnson, wrote about the woman she says is a hero.

“Heroes are hard to come by. I admire a lot of people, but not to the extent to call them a hero. But Harriet Glickman truly is MY hero.”

As far as Harriet, she was proud of Franklin, too, calling him her “third child.”

I love this story because it shows what can be accomplished when people take the time to listen to people who are different from them, to have an open and honest dialogue about a perceived impasse, and then work together to find a way to topple it effectively.

I’m not surprised at all that the Peanuts gang teaches us this one last lesson – it is, after all, what they do best.