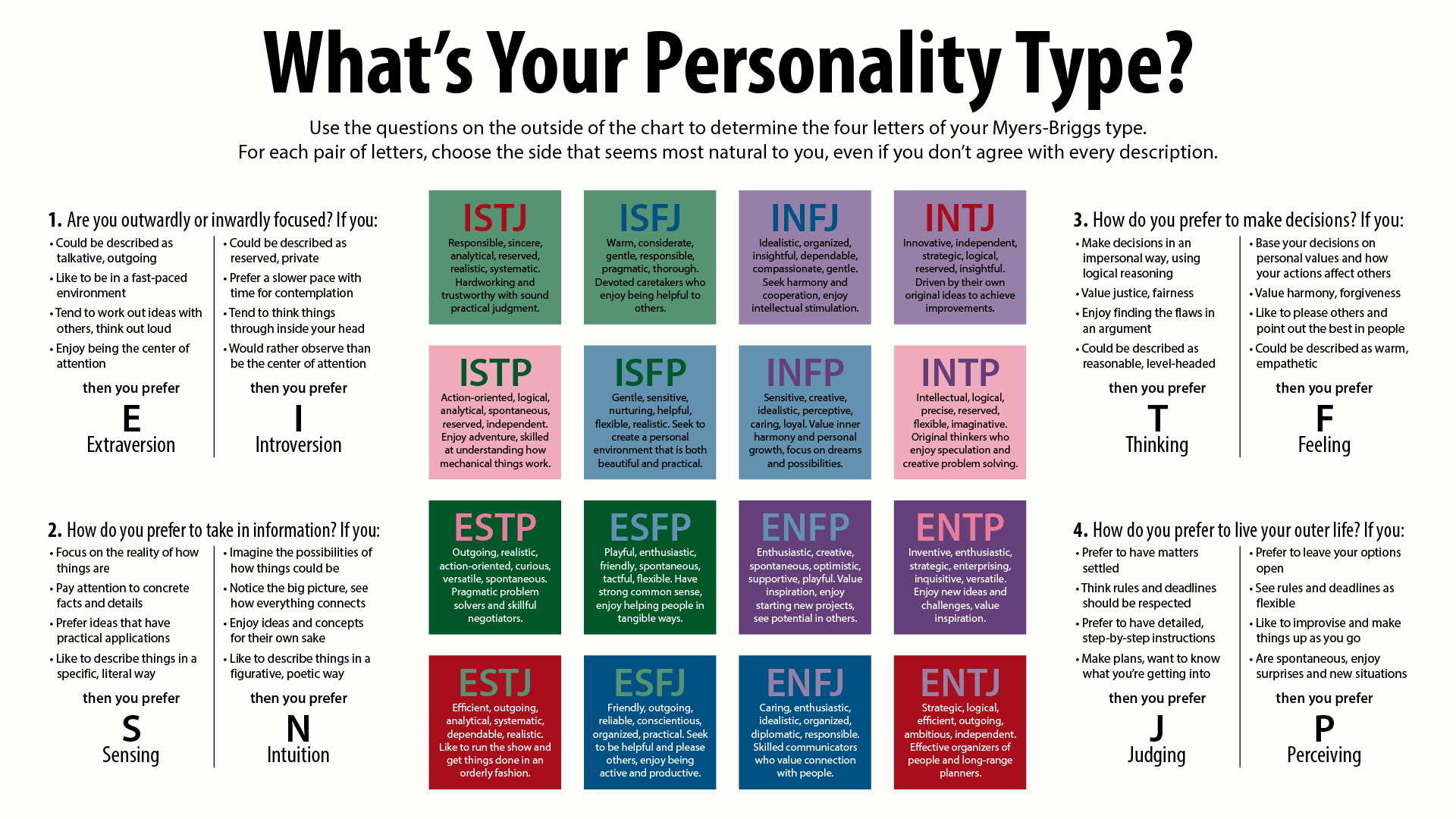

Are you an INTJ, or an ESFP? ISTP, or ENFJ?

Those are just some of the 16 possible results of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), one of the world’s most popular personality tests. You might have even taken it in the past, either just for fun online or at school/work as part of an evaluation. The MBTI has been around since 1942, and is regularly used by Fortune 100 companies, the federal government, and even the military to evaluate incoming candidates and assign them responsibilities and training based on what would be best for that “type.”

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Taking the MBTI can cost you anywhere from $15-$40, and for $1,700 you can become a certified test administrator. With nearly 2 million people taking the test annually, it’s estimated that CPP – the company that produces and markets the test – makes close to $20 million off it per year.

Wow, it sure sounds legit, right? Too bad the MBTI is essentially meaningless.

According to Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at Wharton, “The characteristics measured by the test have almost no predictive power on how happy you’ll be in a situation, how you’ll perform at your job, or how happy you’ll be in your marriage.”

A lot of this has to do with the way the test was created in the first place. The MBTI is based on ideas about personality that had been put forth by psychologist Carl Jung during the 1920s.

Carl Jung, Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Among these ideas was the notion that humans tend to either be “Perceivers” or “Judgers.” Each of these categories could be further split in two – Perceivers might prefer to either sense or intuit, and Judgers could be divided into thinkers or feelers. All of these types could then be divided one last time into being either generally introverted or generally extroverted. Even Jung, however, was careful to note that “Every individual is an exception to the rule,” and that these categories were mere approximations, not absolutes.

In the 1940s, housewife Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother, Katherine Briggs, adapted Jung’s ideas into a personality test. Troublingly, neither had any formal training in psychology and learned statistical analysis and test-making techniques from an HR manager at a Philadelphia bank.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Their test was devised such that people would get a single possibility in each of the four categories, based on answers to a series of two-choice questions. As a finishing touch, they gave colorful titles like “The Executive,” “The Caregiver,” “The Scientist,” and so on, to each of the 16 possibilities.

The problem with all this is that most human traits tend to be somewhere along a spectrum. In fact, Jung himself stated that while binaries are a useful tool to think about people, it’d be silly to assume that someone is entirely one way or the other. “There is no such thing as a pure extrovert or a pure introvert,” he wrote. “Such a man would be in the lunatic asylum.”

Sadly, the MBTI doesn’t make this distinction and is built on the basis that people must either be one thing or the other, with very little room for gray areas. For example, it asks questions like “Do you tend to sympathize with other people?” and gives only “yes” or “no” as choices. It’s not hard to see how a person’s answer to a question like that could change depending on how their day might have been going. As another example, imagine being forced to choose exclusively between thinking or feeling – do you know any sane person who only does one and not the other?

Most damningly, data from the MBTI itself shows that people tend to be more in the middle for any given category, but get pigeonholed into being one or the other exclusively because of the way the test is designed.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons (Click here for full size)

All of this ambiguity has led to a lot of inconsistency as well. It’s reported that nearly 50% of people who take the MBTI get completely different results if they take the test again a few weeks later. That’s certainly not encouraging for a test that’s marketed by CPP as being reliable and scientifically valid. While there are technically plenty of studies confirming this assertion, it’s important to note that they’ve all been published in journals with dubious standing in the scientific community, and the majority of the research was funded by CPP itself.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

It’s also interesting to consider that of all the possible results you can get from the MBTI, not one of them mentions common traits like being lazy, selfish, or just plain mean. It’s not that these kinds of negative personality traits don’t exist, but if you’d just paid $40 to learn about yourself, you wouldn’t exactly be thrilled by the negativity. All of the results of the MBTI are intentionally flattering (and often vaguely applicable to anyone) because it sells more tests.

Within the psychological community, the MBTI is almost completely disregarded for research purposes. Mentions of it tend to come mostly in a historical context, and current personality tests administered by psychologists are a far cry from the test created by Myers and Briggs. In fact, Stanford psychologist Carl Thoresen, who is a CPP board member, even admitted to the Washington Post that using the MBTI in actual research “would be questioned by my academic colleagues.”

While the Myers-Briggs test was certainly a significant innovation in the early days of psychology, the fact of the matter is that in 2018, we can do a lot better. There are several, much more scientifically valid tests out there, including the “Big Five” personality model which has produced consistent results in testing and has even shown promise predicting job success. At this point in time, the MBTI should be considered in the same light as a horoscope: fun to think about, but hardly valid enough to live by.