A nurse on the flight was similarly traumatized by the entire experience, and claims that she couldn’t sleep the entire 30 hour flight. She was “overwhelmed” by the “endless flow of little ones flowing onto the plane filling every available space.”

Jim Trullinger had been conducting doctoral research in Vietnam before being forced to flee on one of the flights. He recalls that there were so many children on the plane that there was nowhere for him to sit. Not only that, but after one of the first Operation Babylift flights crashed weeks before, killing all aboard, including 78 children, he was expected to play his part in saving lives in the event of another catastrophe.

“Before takeoff, one of the flight attendants told me that if there was a crash, I was to get off the plane first and she would toss the babies to me.”

Once the planes arrived in the United States, the babies were off-loaded and triaged. Many of them were ill and required treatment for diseases like dehydration, intestinal illnesses, pneumonia, skin infections, and even things considered mundane in the U.S., like chicken pox.

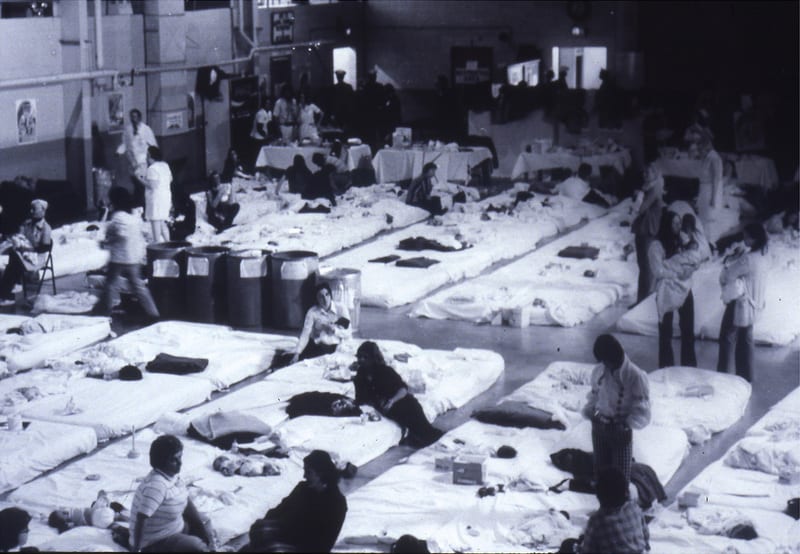

Around half of the children went through The Presidio in San Francisco, a military base that housed a huge, football field-sized building called Harmon Hall that was utilized as a care facility. There, they were under the care of Vietnam vets, nurses, and others who were all under the purview of a local philanthropist named Michael Howe.

The hall was crammed with small mattresses and layers of blankets for children to lay on, with half of the facility devoted to support services like feeding volunteers who worked around the clock. There were occasional reports of people who had been promised babies showing up and stealing them from The Presidio.

Photo Credit: Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives and Records Center

Howe’s first impressions of Harmon Hall and the mass influx of children was disbelief. He remembers thinking, “How did we do this? Did we really do this?”