It seems that as history is becoming more and more relevant to today’s issues, there are more and more people set on destroying it where it has stood undisturbed for thousands of years.

Now, humanity has taken one more step in the wrong direction by destroying ancient cave drawings done by Indigenous Australians.

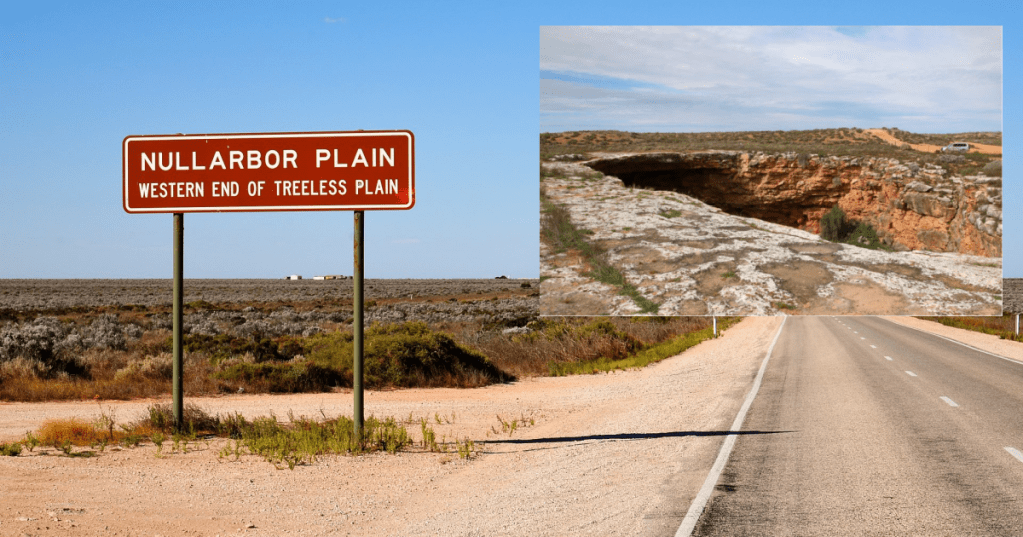

Indigenous art has already taken a bit of a hit lately due to things like mining operations and climate change, but the irreparable damage to the drawings in the Koonalda Cave on the Nullarbor Plain was done deliberately, according to archaeologist Keryn Walshe.

“‘Don’t look now, but this is a death cave’ was scratched into the rock, defacing artworks that had been there for tens of thousands of years. The vandals caused a huge amount of damage. The art is not recoverable.”

The indigenous community, through senior elder Mirning People Uncle Bunna Lawrie, also made a statement.

“Koonalda is one of our most important Whale Dreaming songline places of art and one the last of its kind on this planet. All of our Elders are devastated, shocked, and hurt by the recent desecration of this site.”

The vandalism was not initially reported to the Mirning people, and photographs have been shared without regard to the rules against such things. The Elders say no permission was sought from them to do so.

The carvings in Koonalda are different because they were made by the fingers of Indigenous Australians. They were created near the peak of the last Ice Age, and the images have helped transmit history, culture, and heritage for nearly a thousand generations.

It was first reported by Europeans by Dr. Alexander Gallus in 1956. His age-estimate of 22,000 years nearly tripled the previous record of human presence in Australia at the time.

Lawrie said sadly that his people are “in mourning for our sacred place. Koonalda is like our ancestor. Our ancestor left his spirit in the wall, of the story, of the songline.”

The caves sit nearly 12 hours from a major city, between Perth and Adelaide, inside Nullarbor National Park. The drawings have been considered extremely fragile and have never been displayed for tourists.

The Mirning people have been asking for the site to be secured since 2018, but as the nearest town (of 53 people) is nearly an hour away, it’s possible they did not consider an attack like this likely.

Image Credit: Creative Commons

Attacks on works of indigenous art is fairly common all over the world, though, so hopefully future governments will take this huge loss as a warning to them all.

All the more reason for people to listen when historians talk – if we can use the past to prevent losses in the future, why would we not?