If you’ve attended a children’s science fair, there’s a good chance you’ve seen some version of a Rube Goldberg contraption in action – they’re gizmos that perform a simple task in a ridiculously complicated manner.

Remember the game Mouse Trap? Like that.

There’s actually an entire contest for kids that still happens – the Rube Goldberg Machine Contest – that challenges participants to come up with the wackiest (effective) design possible.

Who was he, though? And why do we remember what he invented?

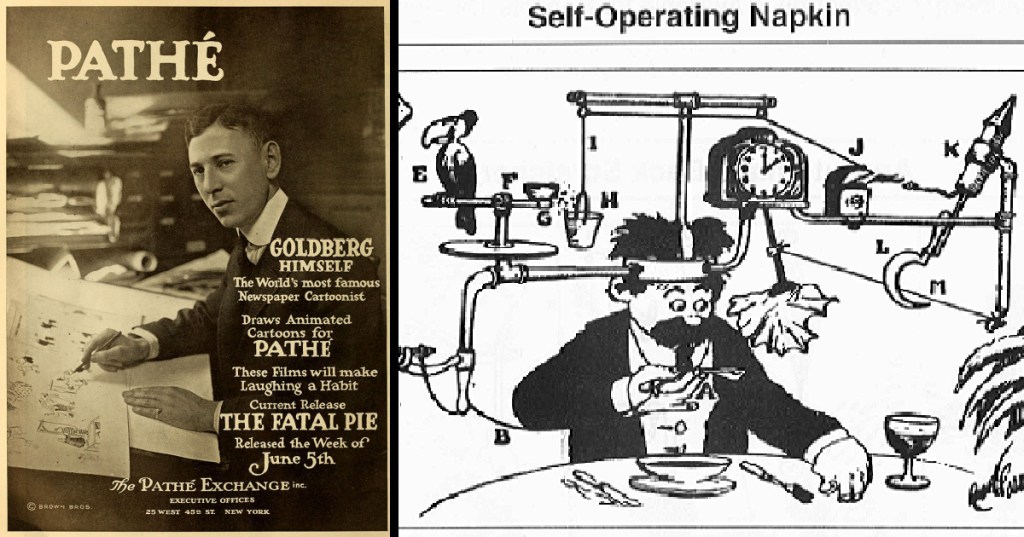

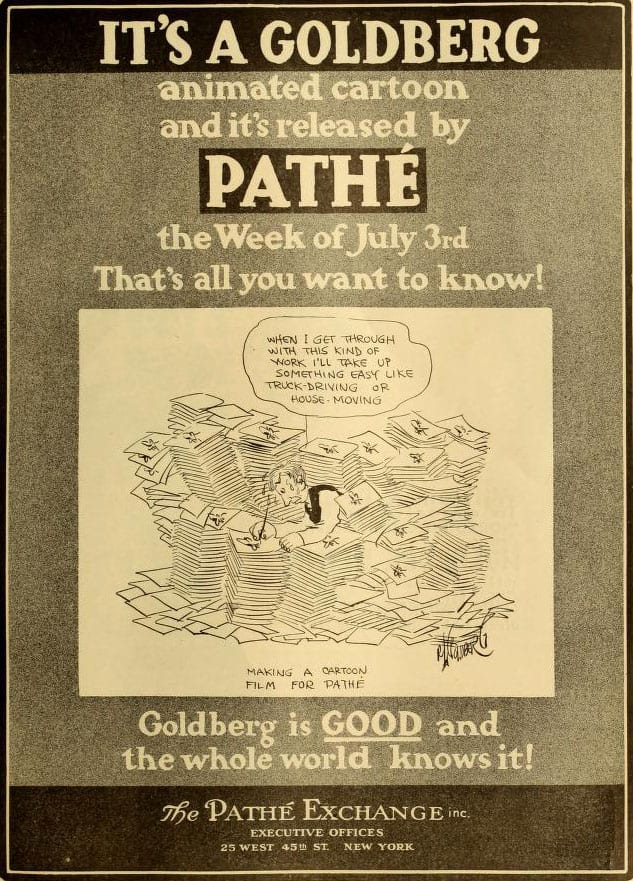

According to Renny Pritikin, chief curator at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, calls him a “rock star” cartoonist of the early 1900s – he drew thousands of cartoons of wacky inventions that appeared in a syndicated column in newspapers all over the country.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary added an entry that reads “Rube Goldberg,” making him the only person whose name is listed as an adjective in the dictionary – fitting, since his name is synonymous with the absurd machinery that made him famous.

Rube Goldberg the man was born in San Francisco in 1883 and worked as an engineer after graduating from college in 1904. He hated the work, and took an entry-level job at the San Francisco Chronicle instead.

Image Credit: Public Domain

His granddaughter, Jennifer George, said in a 2013 book that “What he cared about most was if he made you laugh.”

In 1907 he moved to New York and took a job for the New York Evening Mail, and his cartoons were a huge hit – the first one being his Foolish Questions series.

The next one to take off was “I’m the Guy,” which featured statements like “I’m the guy who put the hobo in Hoboken,” and “I’m the guy who put the sand in the sandwich,” which started a national fad.

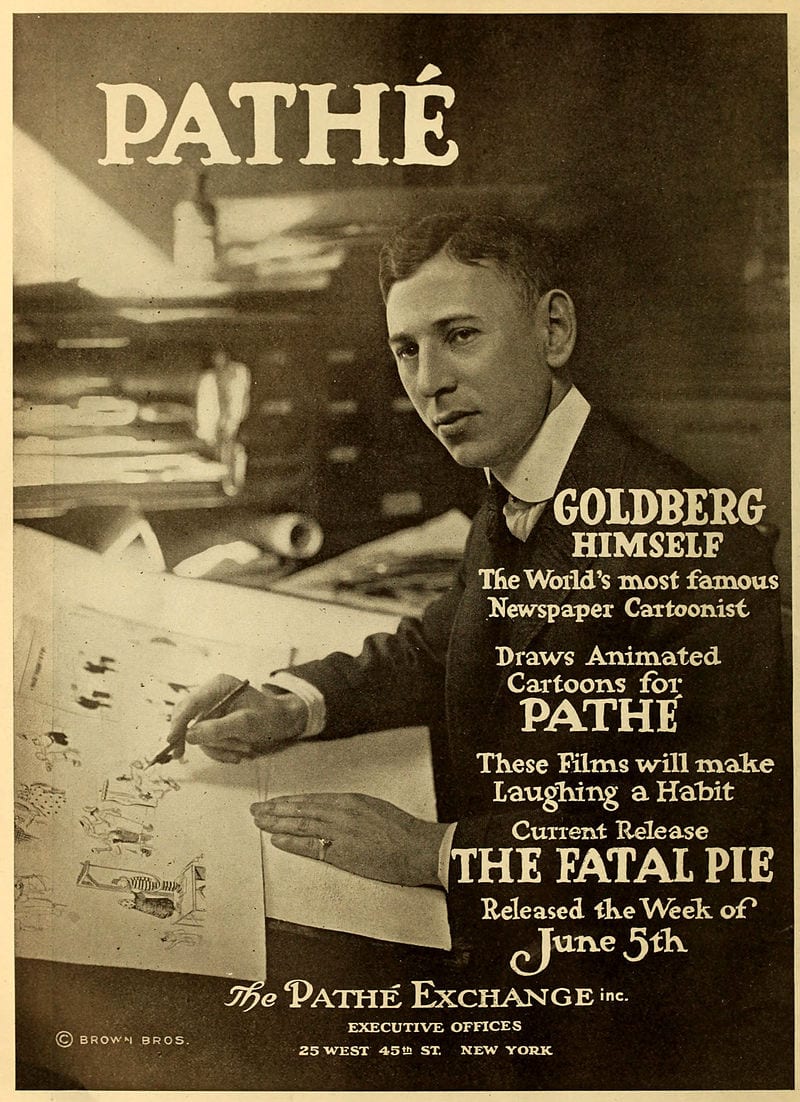

He published his first invention drawings in 1912, and those are what turned him into a household name. The initial idea was “The Simple Mosquito Exterminator,” and went like this:

A mosquito enters window (A), walks along a board strewn with small pieces of steak, falls unconscious because of chloroform fumes from a sponge (B), and falls on platform (C). He wakes up, looks through the telescope (D) to see the reflection of a bald head in a mirror (E), and jumps in fear off spring-board (C) through (D), killing himself when he hits the mirror, falling dead into can (F).

Image Credit: Public Domain

For the next 20 years, he published a new cartoon invention every two weeks, and for 30 years after that he still published, though less frequently. The ideas mocked “the elaborate world of machinery” by mocking the “larger idea of efficiency,” said Adam Gopnik in his biography, following it up with the assertion that Goldberg had “a poetic intuition common to all great cartoonists.”

Pritikin agrees, saying that Goldberg was one of the first voices questioning the use to which technology is put, and commenting on the fact that they sometimes complicate life rather than simplify it.

The conversation they begin is still relevant, then, because as we rush to create and market new things, “we are ignoring a public conversation: Is this good for us or not?”

Image Credit: Public Domain

Goldberg also began drawing political cartoons in 1938 that commented harshly on the rise of fascism, and received a fair amount of criticism for it – though one that depicted a small house balanced on an enormous nuclear missile that’s balanced on a precipice (the caption read: “Peace Today) won a Pulitzer Prize in 1947.

Cartoonists were and remain cultural icons, able to comment on society and connect with people in a unique way that’s really never changed.

And now you know not only why you know the name Rube Goldberg, but why you should – so go out there and enjoy those science fairs just a little bit more!