Trending Now

Stop me if you’ve heard this before: a major snowstorm or blackout blankets a city.

Hundreds of thousands of people are told to stay indoors and hunker down for a day or two until things return to normal.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Nine months later, newspapers report that local maternity wards are seeing an unusual spike in births, complete with a whole bunch of fun little innuendos about how people must have passed the time during the storm.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

This idea of “blackout/blizzard babies” first took hold after the New York Times printed a story in 1966 suggesting that a one-day blackout on November 9, 1965, led to sharp rise in births at local hospitals in the summer of the next year.

The article spoke to several doctors and sociologists – the latter of whom felt that a blackout was a “rich mine for behavioral, sociological and psychological discovery.”

In the end, the article concluded that the blackout was almost certainly to blame.

Essentially, when the lights went off, people started getting it on.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Since then, it’s been the kind of story that seems to do its rounds anytime a major storm or blackout happens.

Take, for instance, the case of the Buffalo hospital reporting a mini “baby boom” after the region experienced a record 70 inches of snow!

Besides blizzard babies, there have also been reports of hurricane babies and even federal government shutdown babies!

Photo Credit: Pixabay

At a surface level, this makes a lot of sense.

Two healthy, willing, able-bodied adults trapped together in the relative comfort of their own home. TV and electricity might be out, leaving very little to do. Lights might be out too, so you light some candles.

There’s a certain sense of impending doom that lends a sense of urgency to the situation and… well…… things happen.

Let’s face it, people have hooked up under wayyyyy less romantic circumstances, and there’s actually Tinder data to prove that people spend more time swiping for “blizzard buddies” during snowstorms.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

But while some steamy, stormy fun makes for a pretty convincing narrative, we don’t deal in compelling narratives here – we deal in facts.

So what does the actual science say about these post-calamity-baby-booms?

It turns out that shortly after that initial New York Times article, a public health scholar named Dr. J. Richard Udry, decided to examine these claims. After closely examining the data from several area hospitals, he found no evidence of any spike in birth rates following the blackout.

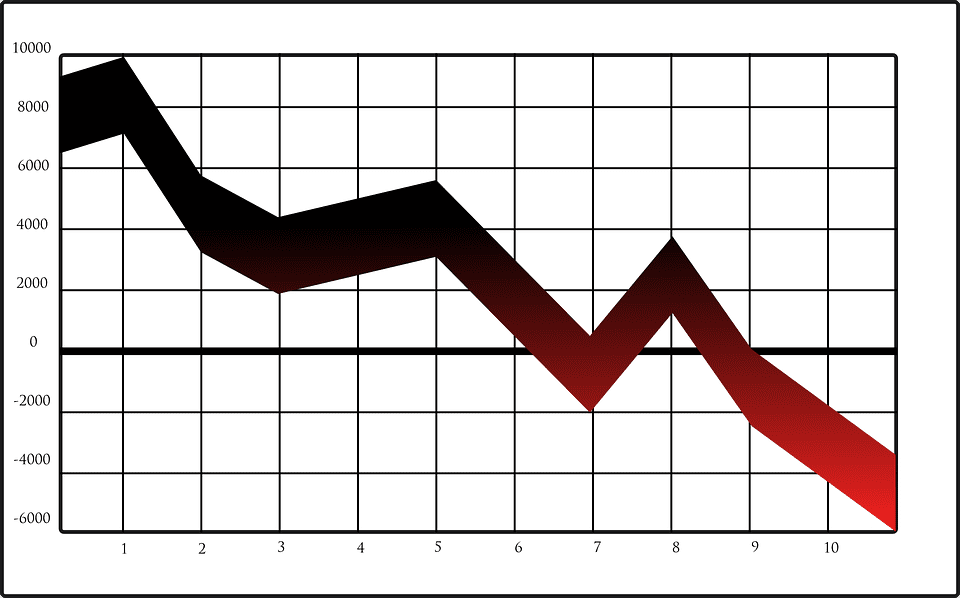

As a matter of fact, his findings actually put the number of babies born in 1966 as being lower than two of the previous four years!

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Still, as is often the case with scientific research, Udry’s study only helped fuel the disaster-birth theory even further.

In the years that followed, newspapers continued to report on disaster babies – something that wasn’t hard to do since they could just cherry-pick the hospitals that would verify their claims and just ignore the others. These reports led many other scholars to turn their attention to the matter, and not all of them came to the same conclusions.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Most notably, a 2008 study published in the Journal of Population Economics examined a much larger sample size of 47 communities around the East Coast over six years.

They found that the severity of the disaster plays a critical role in which way the births are affected.

Specifically, they found that while lower-severity storms and hurricanes did indeed have a small positive effect on birth rates, more severe storms (such as Hurricane Sandy, which killed 157 people) led to a decline.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Richard Evans, one of the researchers, explains,

“With low-level, low-severity storm advisories, we actually found an uptick in births nine months later.

So, it was about a 2 percent increase with tropical storm watches. […]

The other thing we found — that is also intuitive, but no one had ever detected this before — was that, with the most severe storm warnings … you get almost an equal decrease in births nine months later.”

These findings are considered by many to be the most definitive study to date on disasters and fertility, and they make the most sense.

More interestingly, the study also found that the increased fertility effect of a disaster was much more pronounced in couples who already had one or more children.

Photo Credit: Pixabay

Being the economists that they were, the researchers speculated that “This suggests that the elasticity of demand for children is relatively inelastic for first children but becomes more elastic after couples have their first child.” Essentially, a minor disaster isn’t making couples rush into unprotected sex if they don’t have kids, but if they’ve already got kids, they’re more likely to take the risk of conceiving another one.

So, do blizzards and blackouts really cause more babies?

Yes, but only if it’s nothing too serious and you’ve already got a kid.

Just know that, because babies are good for paper sales, news reports of these events are almost always greatly exaggerated.