Trending Now

Irena Sendler was living in Poland at the beginning of WWII, by which point the Germans had made helping Jews punishable by death. But Sendler, raised by a father who believed helping people – all people – who were in trouble was the right thing to do, continued her life as an activist and outspoken critic of antisemitic policies despite the risk to herself and her family.

“I was taught by my father that when someone is drowning you don’t ask if they can swim, you just jump in and help.”

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Irena’s father lived, and eventually died, by his compassionate philosophy – a doctor who treated the poor and young, he passed after contracting typhus from a patient when his daughter was just seven years old. But she learned from him while he was around, and from her mother, as well.

She became a vocal critic of Jewish segregation during her years at school. Irena frequently crossed the aisle to sit with her Jewish friends, and, after one of them was beaten, she sat with them permanently – an act of friendship that earned her a three-year suspension.

When the Germans invaded Poland, Irena was working for the Polish Social Welfare Department and watched as her Jewish co-workers were fired after years of service. Later, she and the others still working there were barred from helping Polish Jews at all.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

With the help of like-minded co-workers, Irena began an operation to create false papers to help Jewish families escape – more than 3,000 documents in total – and she didn’t stop even after the Nazis enacted the death penalty for anyone found to have helped Polish Jews.

In 1943 she joined the Zegota, an underground organization built to help Jewish people escape the Holocaust. She adopted a fake name and headed up the Jewish children’s section.

Sendler had access to the Warsaw Ghetto due to her job with the Social Welfare Department and used her ability to walk in and out to deliver food, medicine, and clothing – and to walk out with children and babies smuggled in ambulances, trams, packages, and suitcases.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

She helped smuggle over 2500 children out of the ghettos, extracting 400 of the personally, and was haunted by the conversations she overheard as parents agonized over whether or not to send their children away or keep them close – knowing that either choice could result in their deaths.

The smuggled children were dispersed among friends and to Christian Polish families; they had to be given Christian names, and they learned prayers and values in case they were questioned. Others were sent to the Catholic orphanages, where they were taught the same skills in order to mask their heritage.

Sendler kept meticulous records, as she had promised parents that when the war ended, she would do everything in her power to reunite the families she had helped. Her lists of whereabouts, new names, given names, and other details were buried in jars underground.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

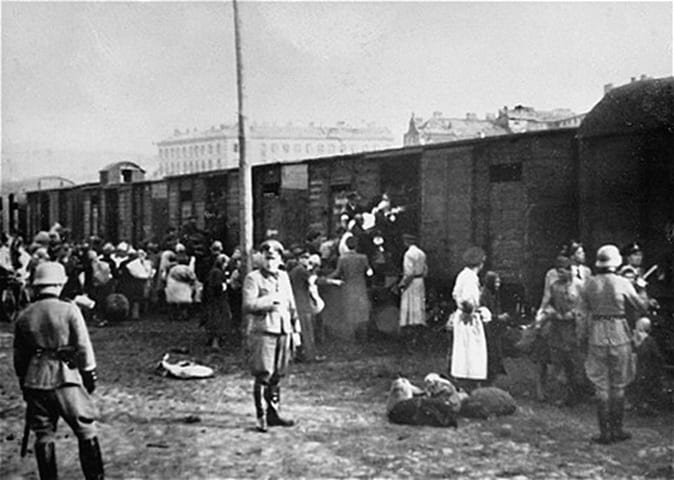

But in 1942, the Nazis began Grossaktion (the Great Action) and began to “resettle” Warsaw’s Jews in concentration camps. Irena Sendler watched her friends – and her hope of reunifying the families – disappear.

A year later, Sendler was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo but did not reveal the identity or location of a single child.

She survived the torture, beatings, and even a death sentence only to return to her job under a new name and continue her work.

After the war, she worked as a nurse as she attempted to bring the children she rescued back to their parents. Sadly, almost all of the families who had remained in the Ghetto had been killed at Treblinka or were missing.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Sendler has been recognized by the state of Israel and received a personal thank you from Pope John Paul II, in addition to receiving Poland’s highest civilian honor, The Order of the White Eagle, and being awarded the Jan Karski Award for “Courage and Heart” by the American Center for Polish Culture.

Irena, though, never put much stock in accolades, awards, or people heaping praise on her in general.

“I was brought up to believe that a person must be rescued when drowning, regardless of religion and nationality. The term ‘hero’ irritates me greatly. The opposite is true. I continue to have pangs of conscience that I did so little.”

Whether or not it irritated her, she was indeed a hero. She passed in 2008 at the age of 98.