The world is looking for clean, affordable, ready energy everywhere – in all of the nooks and crannies, all of the ideas rattling around people’s heads, and anywhere else they can think of. Earth needs us to figure it out, and soon, because the climate crisis is getting out of hand, and fast.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t think I would have thought about looking inside a well (so I guess it’s a good thing I’m not in charge).

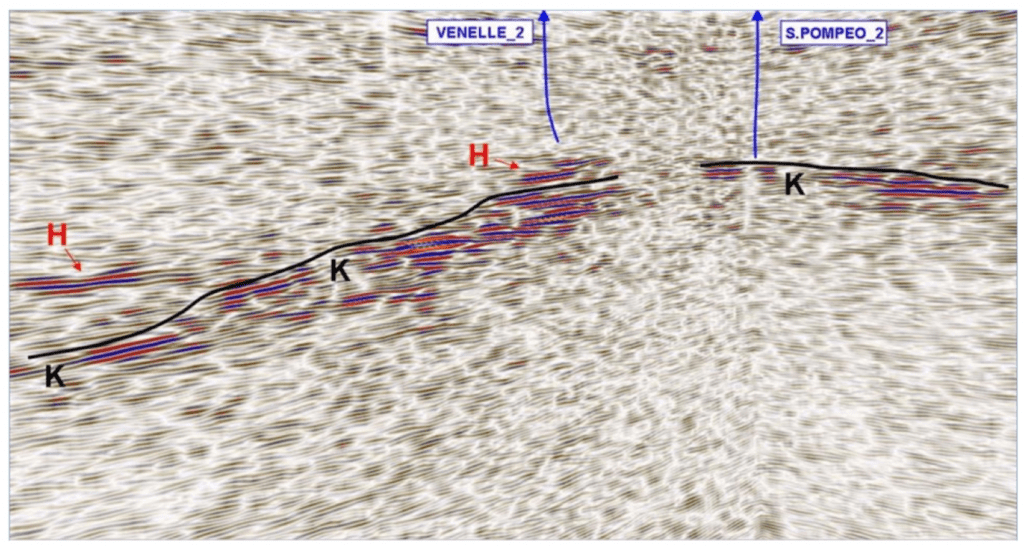

Image Credit: Geo Energy Marketing

The well in question burrows deep into the foothills of the Apennine Mountains, near Tuscany, and reaches almost 2 miles beneath the surface. Temperatures and pressures are so high at that depth that the rock begins to bend, and conditions are great geothermal fluids – mineral-rich water that is both a liquid and a gas.

If the power down there could be used to spin a turbine on the surface, the well could be one of the most energy-dense forms of renewable power in the world.

Of course, there’s always a catch – in this case, it’s that boring that deep into the group risks triggering an earthquake or a rockslide on the surface, and the fact that no one knows what would happened if the drill punched down too far, directly into the layer of gas/liquid.

Temperatures are over 1,000 degrees F down in the well, with pressures 300 times greater than that at the surface, but even so, recent research suggests the drilling could continue without triggering any major seismic activity.

The authors hope their research will encourage more work with geothermal wells in the future.

Image Credit: Geo Energy Marketing

Experiments with supercritical fluids have been ongoing in the US, Japan, Italy, and Mexico for years, but this particular well is the hottest and most pressurized of any they’ve tested thus far – and it’s the only one that has been proven to contain supercritical fluids at all.

There is another, in Iceland, that shows potential, but it’s even deeper than the well in Tuscany.

Back in 2017, seismic activity readings at a different site caused scientists to worry that continued and deeper drilling might induce larger seismic events, which has slowed progress on geothermal wells the world over.

And in places like South Korea, experimental drilling into potential geothermal wells has triggered large earthquakes, so there’s reason to be cautious.

Even if we take seismic activity off the table, geothermal wells have other drawbacks, like supercritical fluid reservoirs being fairly rare, and therefore unlike to be able to transition all of society to geothermal energy.

Image Credit: Geo Energy Marketing

The fluids, too, are problematic, says Susan Petty, president of Hot Rock Energy Research Organization.

“The fluids are very corrosive and dissolve a lot of stuff out of the rock that you need to deal with. It’s scary stuff.”

She, and others, believe we can mimic natural supercritical fluids synthetically, and achieve similar results without so many dangers and risks.

If we didn’t have to depend on natural occurrences and locations, geothermal wells could “provide an inexhaustible source of always-on, carbon-free electricity for the vast majority of the world.”

Image Credit: Hydrogen Fuel News

They still require drilling, though, which means a fear of triggering massive earthquakes remains, and those kinds of risks have made geothermal slow to catch on.

They’re not as sure a thing as wind and solar, and so they haven’t gotten a fair share of the federal funding, either, says Jeffrey Bielicki of Ohio State University.

“Geothermal suffers from a bit of a marketing problem. Even though it has a lot of beneficial characteristics, when people say ‘renewable energy’ they’re usually referring to wind and solar.”

So while geothermal energy might not be coming soon to a power grid near you, it remains another, extremely viable avenue of research.

If we can find a way to do it safely, it might be the most efficient source in the long run, too.