English is widely regarded as one of the toughest languages in the world to learn. There are rules, sure, but they’re kind of more like guidelines and they get regularly broken for really no reason at all.

It was spelled at random until nearly 1600, when some standardization was attempted, but it’s still enough of a mess to give anyone learning it as a second language complete breakdowns on a regular basis.

Which is why, I assume, some people have attempted to make common-sense changes over the years, only to be thwarted because obviously, human beings and change don’t mix – not even when it’s for our own good.

Here are 4 times people have (unsuccessfully) tried to make things a little bit less confusing.

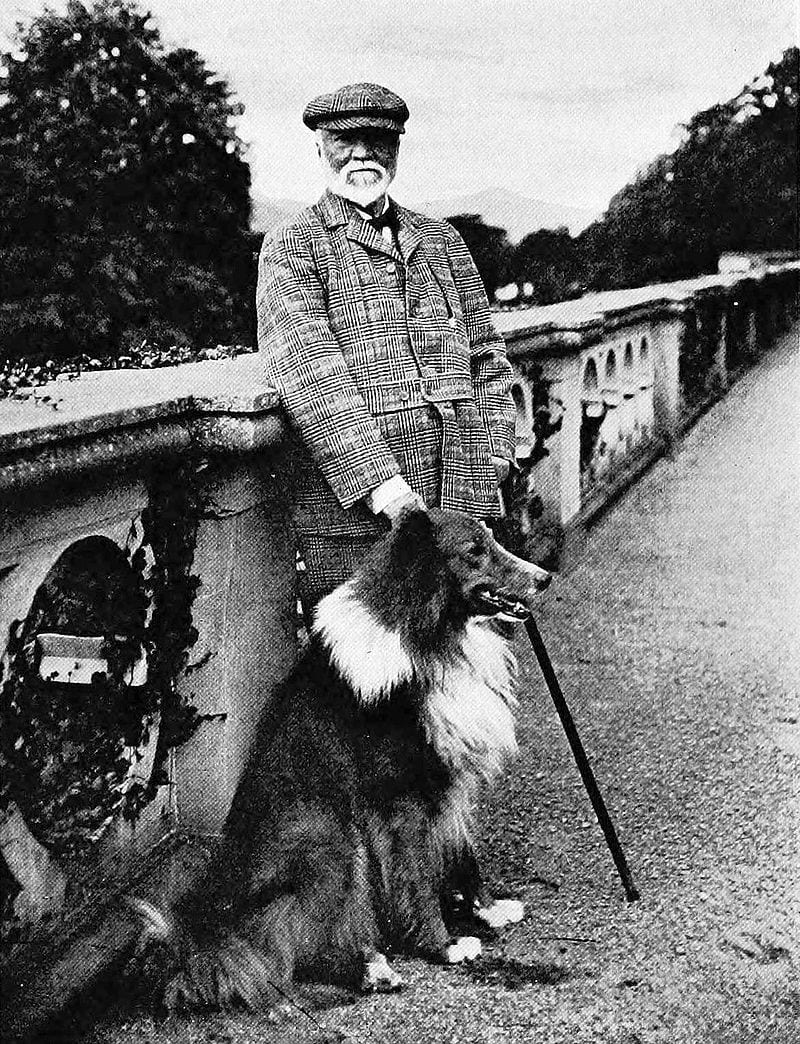

4. Teddy Roosevelt insisted his government use “simplified spelling.”

Image Credit: Public Domain

Spelling reform had become something like trendy by the late 19th century – everyone from Brigham Young to Andrew Carnegie was throwing out suggestions on how to make English easier.

Carnegie thought that English wasn’t catching on with the rest of the world because of its inconsistent spellings, and thought his “Simplified Spelling Board” was the answer. It included a list of 300 revised words (‘rime’ and ‘kist’ instead of ‘rhyme’ and ‘kissed’), and got an unsuspected boost when President Teddy Roosevelt issued an executive order stating that the revised spellings be used in all federal government communications.

Roosevelt’s reason was practical, and came down to the almighty dollar. He believed extra and unnecessary letters were costing millions in printing overheads, which led to pushback from the printing industry, and a bunch of other people that were just too lazy to figure it out.

Across the world, people laughed but Roosevelt stuck to his guns, even delivering a State of the Union written with the revised spellings, many in the government flat-out ignored the order.

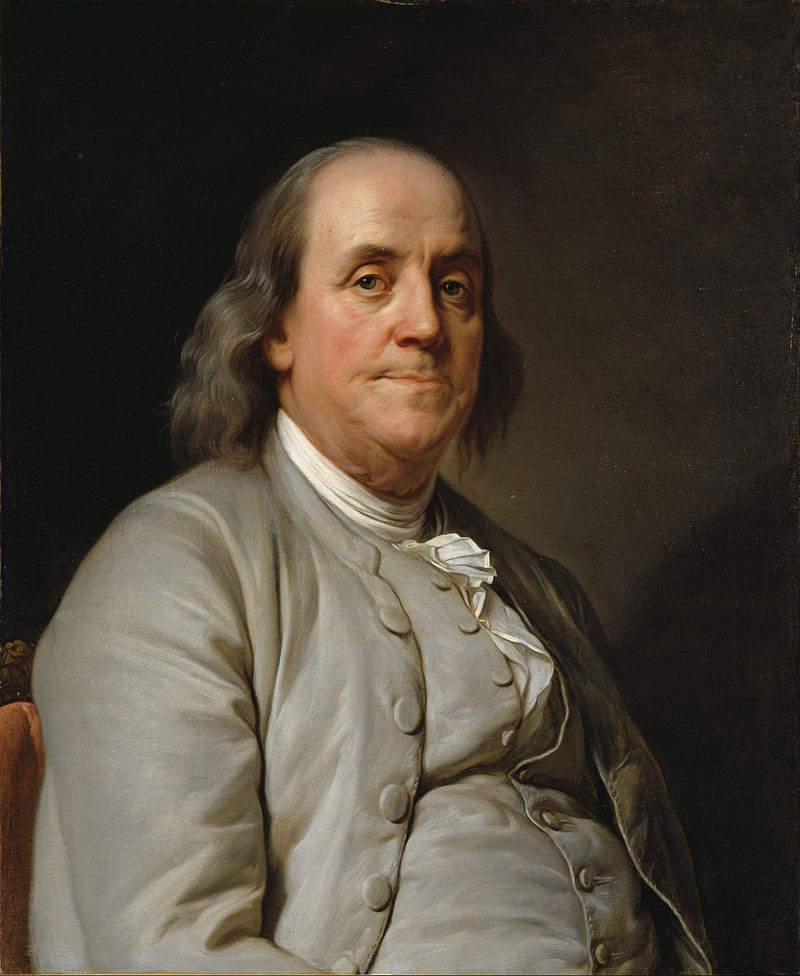

3. Benjamin Franklin had a problem with the letter ‘C.’

Image Credit: Public Domain

Cookie Monster would be appalled, but with an eye on a more phonetic alphabet, Franklin believed the letter ‘C’ should really take a hike.

Modern English allows for letters like C to be pronounced differently depending on context. If you read ‘Pacific Ocean,’ for example, you’re pronouncing the ‘C’ three different ways in a single phrase.

Franklin thought the C was unnecessary, given that we have other letters that already make all of those sounds – K and S, for example – and believed the letters J, Q, W, X, and Y were similarly superfluous.

He proposed 6 new letters to represent commonly used sounds like -ng and ‘sh,’ but honestly, no one was really interested.

2. Noah Webster, who created the Webster’s Dictionary, would have been on board, though.

Image Credit: Public Domain

Webster was also an advocate of spelling reform, and is remembered for launching a war on the letter ‘U’ – he’s why Americans drop the letter in words like ‘color’ and ‘rumor.’ The English added it to act sort of French, because we all know we have to act like we loathe the people we actually want to be the most like.

Webster, like Franklin, was a fan of phonetic spelling, and while it might make more sense to spell ‘soup’ ‘sooop’ and ‘tongue’ ‘tung,’ his efforts were also for naught.

His essay on the subject, published in 1790’s Collection of Essays and Fugitiv Writings, was barely legible, and he was basically mocked by the entire country.

I mean, we already learned one set of sh**ty spellings. No one is going to vote to relearn the entire thing.

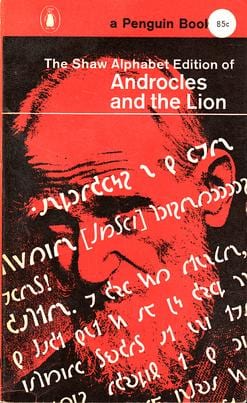

1. George Bernard Shaw’s Shavian Alphabet

Image Credit: Fair Use

Playwright George Bernard Shaw was famously inspired by his passion for spelling reform, but in the end, he too was conquered by English’s absolute refusal to be smoothed out and squared up.

Because of the vastness of English, he struggled with consistency; he removed apostrophes only to realize he needed them sometimes when a word like ‘I’ll’ looked like ‘ill’ without one.

To fix the problem, Shaw chucked English entirely and imagined an entirely new writing system that embraced phonetic English complete. He died in 1950 and left the bulk of the work to a charitable estate – along with a hunk of cash.

The British Museum ended up with most of the money, but a guy called Kingsley Read got the rest, and set about coming up with a system of 48 “short”, “tall,” and “deep” letters that each corresponded with a unit of sound.

He had trouble with publicity, and again, the inherent laziness of human beings, who weren’t into the idea of finding something entirely new.

Maybe someday.

But probably not.

I guess we’re just going with English the way it is, huh? Colonel and everything?

What’s the most confusing part of English for you? Let’s commiserate in the comments!