Trending Now

When you were a kid, did you happen to love reading a series of children’s books that featured a lovable family of bears?

You know, these guys? What were they called again?

Photo Credit: Berenst**n Bears

Did you say “Berenstein” bears… or was it “Berenstain” bears? You’d be right if you said the latter, but you’re definitely not alone if you said “Berenstein.” Up until I started writing this article I was sure that’s what it was too!

Photo Credit: AV Club

If you’re feeling bad about misremembering that, here’s an easy one for you: What was Darth Vader’s iconic line to Luke Skywalker at the end of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back?

Photo Credit: Lucasfilm

Like most people, you probably made a Darth Vader breathing noise (no? Just me, then?) and said, “Luke, I am your father!” It’s surely one of the most memorable movie lines of all time, right?

Wrong: in the real scene, Vader never says Luke’s name. The actual line is “No, I am your father!”

So what’s going on here? How is it that so many people so vividly remember something being one way when it was actually another? Is this some kind of shared mass delusion?

You actually might say that. Both of these are examples of a phenomenon known as ‘The Mandela Effect’, a term first coined by “paranormal consultant” Fiona Broome. She noted that she and several other attendees at a convention all had vivid memories of seeing Nelson Mandela’s funeral after he died in prison in the 1980s. She remembers seeing reports of riots, a massive public funeral, and a heartfelt eulogy by his widow.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

… Except for the fact that Nelson Mandela was released from prison, went on to be elected the first black President of South Africa, and didn’t die until 2013.

Broome speculated that perhaps so many people have such strong memories of things that apparently never happened because they’re actually slipping in and out of alternate timelines. People remember Mandela’s death because he did die in prison – in a different timeline. Several people from that timeline then somehow slipped into ours, in which Mandela didn’t die until 2013.

Others suggest that maybe this is a case of the “Many Worlds” theory inspired by quantum physics, which posits that a new universe is created each time an event with multiple possible outcomes occurs – one for each outcome. Then, of course, you’ve got theories that attribute these memory distortions to black magic, Satan, and witches. You know, standard crazy person stuff.

Photo credit: FX

What about the science?

This is where we come back to Earth – this Earth, the only one we know of so far. You see, a big part of the issue here is that people think that their memories work like a video recorder – we record every detail and can call it up perfectly whenever we need. Unfortunately, science has found over and over again that our memories are far from perfect.

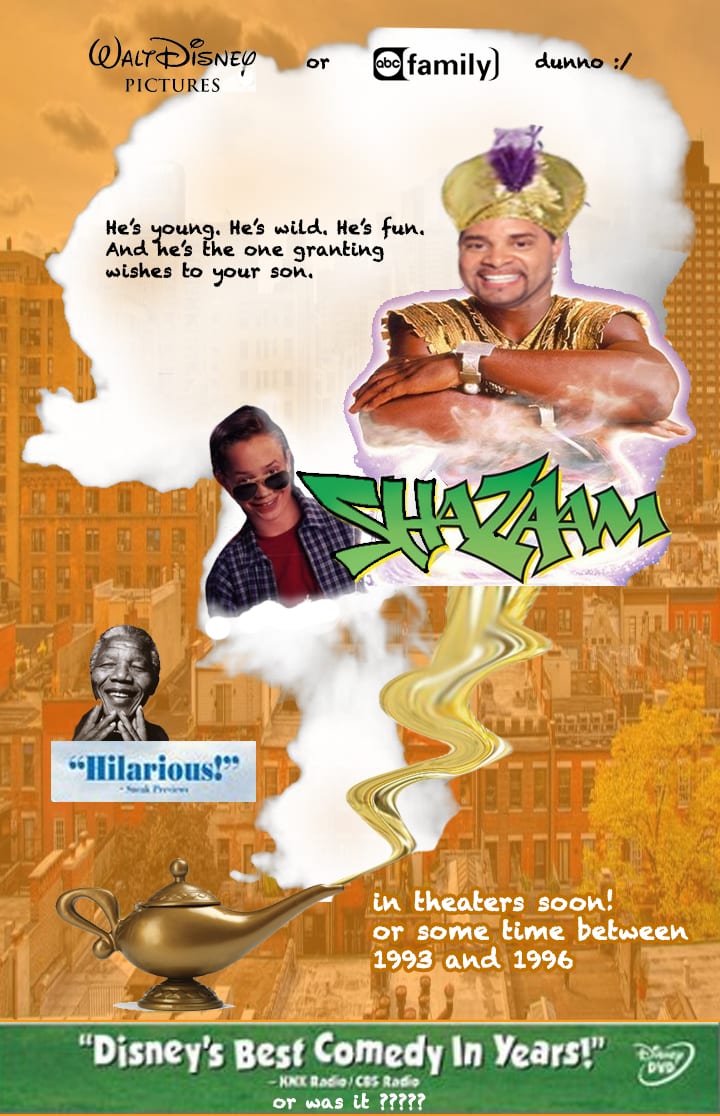

The scientific term for a distortion or misinterpretation of memory without any intent to deceive is “confabulation”. Confabulations can range from subtle, innocuous alterations to a recollection, such as confusing which friend you went to that Mexican spot with, all the way to truly elaborate fabrications… like the mass funeral of a beloved political icon or that genie movie with Sinbad that so many people “swear” they saw as a kid.

Photo Credit: Imgur

A famous experiment on memory is the Deese, Roediger, and McDermott (DRM) task, in which participants were presented with lists of semantically related words (ex: nurse, hospital, etc.) and then later asked to recall the words. They found that people routinely recalled words that were related, but not on the actual list (such as “doctor”).

Even scarier still is just how easily our memories can be manipulated. In a now-famous experimental technique titled “Lost in the Mall,” psychologist Jim Coan (then an undergrad doing an extra credit assignment) devised an experimental technique to implant a false memory about his brother getting lost in the mall as a child into his family members. Incredibly, the brother in question even started adding his own details to the narrative, and expressed disbelief when the ruse was finally revealed.

Coan and his professor, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, went on to do groundbreaking work in the field of false memories and memory implantation, with some truly startling findings. False memories are shockingly easy to implant, which can lead to some truly horrifying consequences – particularly within the criminal justice system.

Photo credit: Pixabay

Psychologists believe part of the reason why these things might happen is that we organize our memories using a system of schemas, “packets” of information that influence what is remembered. This was outlined by Frederic Bartlett in 1932, when he found that listeners of a folktale tended to omit unfamiliar details in the story and adjusted the narrative to be easier to understand.

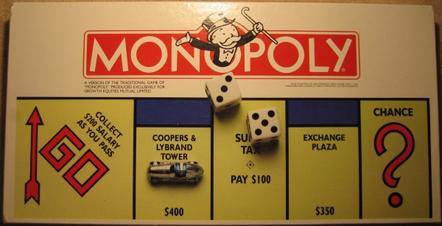

Scientists would, therefore, say that this issue of schemas is the reason so many people think Uncle Pennybags (the Monopoly man) has a monocle when he doesn’t. It’s because our schema of old-timey rich guys includes monocles, top hats, mustaches, bow ties, and tuxedos. We simply fill in the one trait that’s missing from Uncle Pennybags.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

What it all means

While it would certainly make for a more interesting existence if we had people slipping between worlds/dimensions or time travelers affecting the way we remember things, the simple truth is that most of us give our memories a little too much credit.

We’re always evaluating new information to see if it has any value to previously formed memories, and our brains are constantly filling in details based on what makes sense (like the Monopoly man’s monocle). Our memories aren’t set in stone – in fact, they’re constantly evolving. That’s why your Uncle Joe’s legendary “fish that slipped the line” gets bigger every year!

Photo credit: Pixabay

The more details we add, the greater the likelihood of feeling invested in that memory, which can eventually lead to a much higher level of cognitive dissonance and resistance when the truth is revealed. At the end of the day, though, it’s important to remember that we excuse ourselves all the time for making mistakes because “we’re only human”, and our memories deserve the same kind of slack too.

If you enjoyed reading this, check out:

Do You Hear ‘Brainstorm’ or ‘Green Needle’? Whichever You’re Thinking about Is What You’ll Hear